محمود مختار اولین مجسمه ساز از سرزمین مجسمه سازی

محمود مختار (1891-1934) که برجسته ترین مجسمه ساز مدرن مصر شناخته میشود در سراسر مسیر شغلی خود بین قاهره و پاریس در رفت و آمد بوده است؛ او زیباشناسی پیکرتراشی را با تصورات مصر باستان ترکیب می کرد. مجموه آثار او و خصوصاً شاهکارهاش – بیدارسازی مصر (1920-1928) – راهی را برای تجسم بصری ملت-دولت مصری جدید برای مردم فراهم ساخت. آثار هنری مختار، ماهیت فراملی دنیای هنر در اوایل قرن بیستم و در نتیجه، اهمیت ملت در آن دنیا را نشان میدهد.

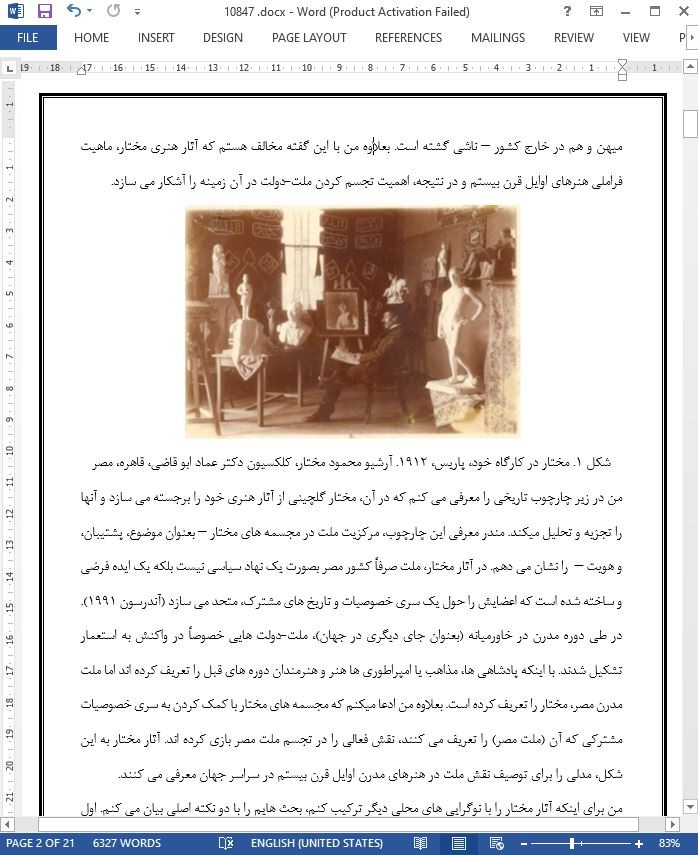

در یک عکس از سال 1912، مجسمه ساز مصری جوان، محمود مختار (1891-1934) در کارگاه پاریس خود لم داده است و در اطرافش جسمه های آکادمیک به سبک فرانسوی و خطاطی های عربی آویزان شده روی دیوار قرار دارند (شکل 1). در سمت راست مجسمه ای با ظاهر حقیقی از یک مرد برهنه وجود دارد که به حالت contrapposto ایستاده است و در قسمت بالای سمت چپ متن اعتراف به دین اسلام (هیچ خدایی جز الله نیست و محمد پیامبر او است) وجود دارد که متن آن با نخ سفید بر روی یک پس زمینه سیاه دوخته شده است. مختار در بین این سنت های بصری به ظاهر متناقض، نشسته است و با آرامش در حال طراحی است. این یک عکس فوری و اتفاقی نیست: هنرمند بصورت عمدی خودش و کارگاهش را به این شکل مرتب کرده است تا همزمان فرهنگ عربی-اسلامی و هنرهای اروپایی را نشان دهد. من در این مقاله به بررسی این مسئله می پردازم که مختار چطور و چرا در اوایل مسیر شغلی اش از مراجع اسلامی به سبک فرعون گرایی رو می کند، که بر خلاف سبک اسلامی، بر تصورات مصر باستان متمرکز است. من ادعا میکنم که این تغییر سبک از مشارکت مختار در تجسم کردن یک حالت مدرن از ملت-دولت مصر – هم در میهن و هم در خارج کشور – ناشی گشته است. بعلاوه من با این گفته مخالف هستم که آثار هنری مختار، ماهیت فراملی هنرهای اوایل قرن بیستم و در نتیجه، اهمیت تجسم کردن ملت-دولت در آن زمینه را آشکار می سازد

Considered Egypt's most prominent modern sculptor, Mahmoud Mukhtar (1891–1934) moved between Cairo and Paris throughout his career, blending a modern European sculptural aesthetic with ancient Egyptian imagery. The resulting oeuvre of work, and especially his masterpiece, Egypt's Reawakening (1920–28), provided the populace with a way to visually imagine the new Egyptian nation-state. Mukhtar's artwork reveals the transnational nature of the early twentieth-century art world and the consequential importance of the nation within that world.

In a 1912 photograph, the young Egyptian sculptor Mahmoud Mukhtar (1891–1934)1 relaxes in his Paris studio, surrounded by French-style academic sculptures and calligraphic wall-hangings in Arabic (Figure 1). On the right stands a verisimilar sculpture of a nude man in contrapposto pose, and in the upper left appears the creed of the Muslim faith – ‘There is no god but God and Muhammad is his prophet’ – sewn in white wobbly script on a dark background. Mukhtar sits and sketches tranquilly amid these seemingly contradictory visual traditions. This is not a casual snapshot: the artist consciously positioned himself and his studio to represent his grounding in both Arabo-Islamic culture and European fine arts. In this paper, I investigate how and why Mukhtar made the transition from Islamic references early in his career to a style known as Pharaonism, which instead looked to ancient Egyptian imagery. I argue that this shift resulted from Mukhtar’s participation in imagining the modern nation-state of Egypt, both at home and abroad. Moreover, I contend that Mukhtar’s artwork reveals the transnational nature of the early twentieth-century art world and the consequential importance of visualizing nation-states within that context.

- اصل مقاله انگلیسی با فرمت ورد (word) با قابلیت ویرایش

- ترجمه فارسی مقاله با فرمت ورد (word) با قابلیت ویرایش، بدون آرم سایت ای ترجمه

- ترجمه فارسی مقاله با فرمت pdf، بدون آرم سایت ای ترجمه