جریانات پول، قطرات آب: شناخت الگوهای تامین آب به روش نامتمرکز در تانزانیا

چکیده

در طول سه دهه اخیر، دولتها در بسیاری از کشورهای کمدرآمد و دارای درآمد متوسط، تامین آب را به مسئولان محلی تفویض نمودهاند و تلاش کردهاند که مصرفکنندگان را در ارائه این خدمات مشارکت دهند. چنین اصلاحاتی نشاندهنده اهداف دوجانبه تشویق مقامات دولتی به پاسخدهی بیشتر به نیازهای محلی و ارتقاء توسعه پایدار در جامعه است. هدف این مطالعه آن است که نشان دهد چگونه اهداف تمرکززدایی میتواند به دلیل فقدان رقابتهای سالم مردمسالارانه دچار آسیبهایی گردد، و تفسیر دولتها از ”تقاضای“ رأی دهندگان چگونه است. این مقاله با تمرکز بر صنعت تامین آب در کشور تانزانیا، به پیگیری چگونگی توزیع پول از دولت مرکزی به بخشها برای ایجاد زیرساخت تامین آب میپردازد. سپس با استفاده از دادههای مربوط به 75,000 نقطه تامین آب که به مناطق روستایی کشور تانزانیا آبرسانی میکنند و مختصات ارضی آنها تعیین شده است، چگونگی استفاده از این منابع مالی توسط مقامات هر یک از بخشها برای ایجاد زیرساختهای تامین آب در حوزه استحفاظی آنها بررسی میشود. در ضمن این مطالعه ما دریافتیم که پول تخصیص یافته توسط دولت مرکزی تانزانیا بدون توجه به نیازهای واقعی افراد بوده است. اگرچه، به استثنای پارتیبازی مستمری که برای استانی که وزیر تامین آب کشور تانزانیا در آنجا ساکن است وجود داشته است، الگوی توزیع پول تخصیص یافته برای تامین آب در این کشور را نمیتوان صرفا بر اساس موضوعات سیاسی توضیح داد. پارتیبازی سیاسی در سطح مسئولان محلی شدیدتر بوده است. در هر یک از این استانها، توزیع زیرساخت جدید برای تامین آب، به نفع اکثریت افرادی است که به سمت طرفداران حزب حاکم گرایش دارند. همچنین، گروههای ثروتمندتر و دارای ارتباطات بهتر، یعنی گروههایی که منابعی در اختیار دارند که بهتر میتوانند تقاضای خود را مطرح کنند، شانس بیشتری برای استفاده از این امکانات مربوط به تامین آب دارند. این بدان معناست که رویکردهای ”پاسخدهی بر اساس تقاضا“ برای تامین آب میتواند الگوهای امتناع از تخصیص منابع را محدود کند.

1. مقدمه

از سالهای 1980 تاکنون، حداقل 41 کشور خدمات مربوط به آب و فاضلاب را به مسئولان محلی واگذار نمودهاند (هرِرا، 2014). چنین اصلاحاتی نوعا شامل خدماتی است که تقاضا، مالکیت، و پشتیبانی خدمات مرتبط با تامین آب را بر عهده مصرفکنندگان قرار میدهد. (لاکوود و اسمیت، 2011). تامین آب به شکل نامتمرکز با هدف پاسخدهی بیشتر به نیازهای محلی انجام میشود. به طور کلی، نزدیکتر کردن دولت به کسانی که تحت مدیریت دولت قرار دارند باید شناسایی و تعیین جمعیت نیازمند به خدمات را تسهیل کند (کروک، 2003؛ گالاسو و راوالیون، 2005) و توبیخ عملکرد ضعیف یا پاداش به عملکرد خوب از طرف مسئولان محلی را برای شهروندان آسانتر نماید (فاگوئت، 2012). وقتی مصرفکنندگان آب بتوانند تصمیمات هوشمندانهای برای سطح خدمات مطلوبشان اتخاذ کنند و به مشارکت در صرف هزینههای نگهداری و تعمیر زیرساختهای تامین آب تشویق شوند، انتظار میرود که توسعه پایدار ارتقاء یابد (کوهلر، تامسون، و هوپ، 2015).

7. نتیجهگیری

ارائه خدمات نامتمرکز فرصتها و چالشهایی را برای دولتها و شهروندان در کشورهای کمدرآمد پدید میآورد. این چالشها در وضعیت تسلط حزب حاکم بر کشور تشدید میشوند که ما این موضوع را در صنعت تامین آب کشور تانزانیا در این مقاله نشان دادهایم. در سطح ملی، به استثناء پارتیبازی که در مورد زادگاه مقامات سیاسی مشاهده میشود، دخالت سیاسی در تخصیص پول به مناطق آشکار نیست. به نظر میرسد که عوامل سیاسی تاثیر بیشتری بر سطوح محلی تقسیمات کشوری دارند. تحلیلهای پیشین نشان میدهند که نمایندگان هر یک از تقسیمبندیهای کشوری که از حزب حاکم حمایت میکنند، منابع مالی را به سمت حامیان خود هدایت مینمایند. این اقدام نه فقط تضمینکننده مسیر شغلی آنها است، بلکه ضامن حیات طولانیمدت حزب حاکم نیز است. به همین دلیل، به نظر میرسد که مسئولان محلی کشور تانزانیا در برابر رؤسای حزب حاکم بیش از رأیدهندگانی که آنها را انتخاب کردهاند پاسخگویی بیشتری دارند. این الگو تخصیص منابع موجب شده است که محرومترین نقاط کشور فاقد دسترسی به خدمات عمومی حیاتی باشند.

Summary

Over the past three decades, an increasing number of low- and middle-income countries have decentralized water provision to the local government level, and have sought to more thoroughly involve users in service delivery. Such reforms reflect the twin goals of encouraging greater responsiveness to local needs and promoting sustainability. This study illustrates how the aims of decentralization can be undermined in the absence of robust democratic competition, and how governments interpret “demand” by voters in such settings. Focusing on the Tanzanian water sector, the paper first traces the distribution of money for water from the central government to the district level. Next, I consider how district governments use these funds to distribute water infrastructure within their jurisdictions, using geo-referenced data on all 75,000 water points serving rural Tanzanians. I find that the central government’s allocation of money to districts is fairly unresponsive to local needs. However, the pattern of distribution cannot primarily be explained by politics, with the exception of consistent favoritism of the Minister for Water’s home district. Political favoritism is more pronounced at the local level. Within districts, the distribution of new water infrastructure is skewed to favor localities with higher demonstrated levels of support for the ruling party. In addition, wealthier and better-connected communities—those with the resources to more effectively express their demands—are significantly more likely to benefit from new construction. This suggests that “demand-responsive” approaches to water provision can entrench regressive patterns of distribution.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the 1980s, at least 41 countries have decentralized water and sanitation services to subnational governments (Herrera & Post, 2014). Such reforms have typically included provisions requiring water users to demand, own, and maintain their water services and participate in their design (Lockwood & Smits, 2011). Decentralized water provision aims to engender greater responsiveness to local needs. In general, bringing government closer to the governed should facilitate the identification and targeting of needy populations (Crook, 2003; Galasso & Ravallion, 2005), and make it easier for citizens to sanction or reward poor or good behavior on the part of local officials (Faguet, 2012). Moreover, having water users make informed choices about their preferred service level is expected to promote sustainability, by encouraging users to contribute to the upkeep of water infrastructure (Koehler, Thomson, & Hope, 2015).

7. CONCLUSION

Decentralized service delivery provides a number of opportunities and challenges to the governments and citizens in lowand middle-income countries. The challenges are exacerbated in the context of dominant party rule, as I illustrate with the case of the Tanzanian water sector. At the national level, political interference in the allocation of money to districts is not obvious, with the exception of consistent hometown favoritism. Political factors appear to exert greater influence at the local level. The preceding analysis suggests that ward councillors affiliated with the ruling party channel resources to their core supporters. This serves to not only secure their careers but also the longevity of the ruling party. As such, Tanzania’s ward councillors appear to be more accountable to party bosses than to the constituents who elected them. This pattern of allocation has resulted in leaving many of the neediest communities without access to a vital public service.

چکیده

1. مقدمه

2. تمرکززدایی تامین آب: وعدهها و واقعیت

3. ویژگیهای خاص کشور تانزانیا

(الف) اوضاع سیاسی کشور تانزانیا

(ب) تجربه کشور تانزانیا از تمرکززدایی

(ج) تامین آب نامتمرکز در کشور تانزانیا

4. تخصیص منابع مالی در دولت مرکزی

(الف) فرضیات (تخصیص منابع مالی در دولت مرکزی)

(ب) راهبرد تجربی (تخصیص منابع مالی در مناطق)

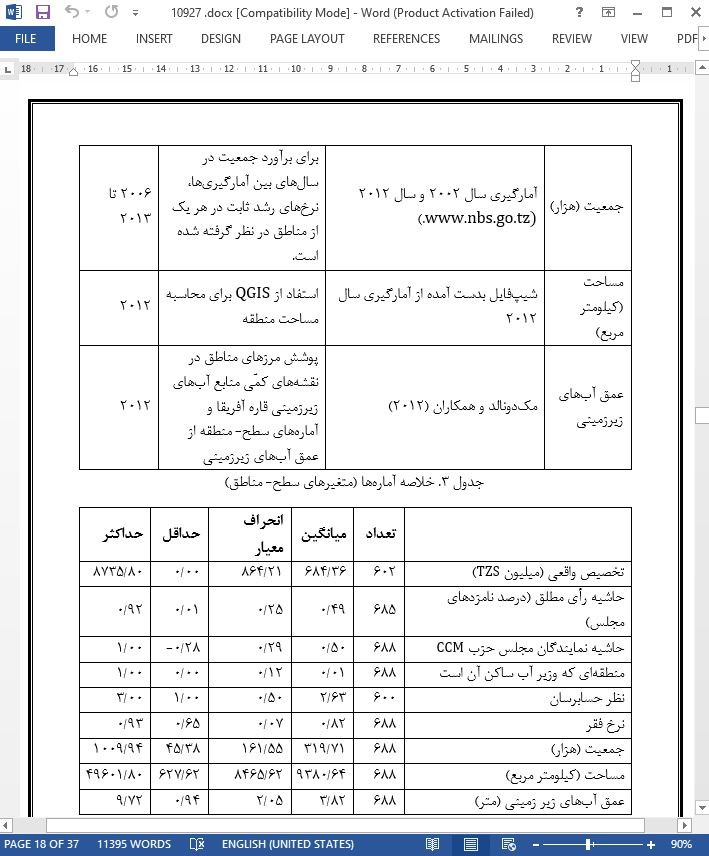

(ج) دادههای سطح- مناطق

(د) نتایج: تخصیص منابع مالی به هر یک از مناطق

5. تخصیص نادرست منابع مالی به دلایل سیاسی توسط مسئولان محلی

(الف) فرضیات (تخصیص منابع مالی توسط مسئولان محلی)

(ب) راهبرد تجربی (تخصیص منابع مالی به هر یک از بخشها)

(ج) دادههای سطح-بخش

(د) نتایج: توزیع زیرساختهای در هر یک از مناطق

6. تشریح مباحث

7. نتیجهگیری

Summary

1. INTRODUCTION

2. DECENTRALIZATION OF WATER PROVISION: PROMISE AND REALITY

3. THE TANZANIAN CONTEXT

(a) Politics of Tanzania

(b) Tanzania’s experience with decentralization

(c) Decentralized water provision in Tanzania

4. CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ALLOCATIONS

(a) Hypotheses (central government allocations)

(b) Empirical strategy (allocation of funds to districts)

(c) District-level data

(d) Results: financial allocations to districts

5. POLITICIZED MISALLOCATION BY LOCAL GOVERNMENTS

(a) Hypotheses (Local Government allocations)

(b) Empirical strategy (allocation of infrastructure to wards)

(c) Ward-level data

(d) Results: distribution of infrastructure within districts

6. DISCUSSION

7. CONCLUSION

- اصل مقاله انگلیسی با فرمت ورد (word) با قابلیت ویرایش

- ترجمه فارسی مقاله با فرمت ورد (word) با قابلیت ویرایش، بدون آرم سایت ای ترجمه

- ترجمه فارسی مقاله با فرمت pdf، بدون آرم سایت ای ترجمه