درک چرخه های واقعی کسب و کار

دهه 1960 دوره خوشبینی اقتصاددانان بود. بسیاری از اقتصاددانان چرخه کسب و کار را مرده میانگاشتند. الگوی حاکم مدل کینزی بود و این مدل همه دستورالعملهای لازم برای اداره اهرمهای سیاست پولی و مالی جهت کنترل تقاضای کل را ارائه میکرد. اگر تقاضای کل «بیش از حد» باشد تورم رخ میدهد و اگر «ناکافی» باشد بیکاری افزایش مییابد. سیاستگذارانی که با این مسأله غامض رو به رو بودند مطلوبترین مکان را در این مبادله تورم-بیکاری یا نمودار فیلیپس تعیین میکردند. چالش فکری باقیمانده ایجاد پایههای اقتصادی پایدار برای روابط رفتاری کل طبق چارچوب کینزی بود. اما این امر بیشتر به عنوان موضوعی لحاظ شد که نباید سیاستگذاران را در تلاش خود برای «باثبات سازی» اقتصاد بر حذر بدارد.

بازگشت چرخه کسب و کار در دهه 1970، یعنی بعد از تقریباً یک دهه توسعه اقتصادی، به همراه نرخ بالای تورم بیداری ناگواری برای اقتصاددانهای بسیاری محسوب میشود. کاملاً مشخص شد چارچوب کینزی نه ابزار مناسبی برای درک روال اتفاقات در چرخه کسب و کار است و نه قادر به ارائه پاسخهای درست تجربی به پرسشهای مربوط به تغییرات محیط اقتصادی یا تغییرات سیاست پولی و مالی است. زمانی این دیدگاه وجود داشت که اقتصاد کینزی حتی اگر فاقد بنیان نظری معقول باشد، یک موفقیت تجربی محسوب میشود. اما دیگر این دیدگاه جدی گرفته نمیشود.

نقص اصلی بیان کینزی از پدیدههای اقتصاد کلان فقدان بنیانی محکم مبتنی بر چهارچوب نظری انتخابی در علوم اقتصاد خرد بود. دو مقاله مهم، یکی از میلتون فریدمن (1968) و دیگری از رابرت لوکاس (1976)، کاملاً نمونههای این نقص را در جنبههای بحرانی استدلال کینزی نشان داد و اولین گامهای اقتصاد کلان مدرن را برداشت.

ویژگی اصلی نظام کینزی در دهه 1960 مبادله تورم و مقدار برونداد واقعی یا بیکاری بود. به گفته فریدمن طبق اصول پایه اقتصاد خرد نمودار بلندمدت فیلیپس باید عمودی باشد. یعنی، اصول کلی اقتصاد خرد میگوید افراد (بنگاهها) مطلوبیت (سود) خود را به حداکثر میرسانند و این امر در نمودار تقاضای (و عرضه) واقعی اثر میگذارد که مشابه درجه صفر در قیمتهای اسمی و درآمد پولی است. بنابراین تورم پایدار با هر سطحی از تقاضا (یا عرضه) واقعی کالا سازگار بود. در نتیجه عقیده اصلی کینزی به شدت با اصول اقتصاد خرد تناقض داشت.

The 1960s were a time of great optimism for macroeconomists. Many economists viewed the business cycle as dead. The Keynesian model was the reigning paradigm and it provided all the necessary instructions for manipulating the levers of monetary and fiscal policy to control aggregate demand. Inflation occurred if aggregate demand was stimulated "excessively" and unemployment arose if demand was "insufficient." The only dilemma faced by policymakers was determining the most desirable location along this inflation-unemployment tradeoff or Phillips curve. The remaining intellectual challenge was to establish coherent microeconomic founda tions for the aggregate behavioral relations posited by the Keynesian framework, but this was broadly regarded as a detail that should not deter policymakers in their efforts to "stabilize" the economy.

The return of the business cycle in the 1970s after almost a decade of economic expansion, and the accompanying high rates of inflation, came as a rude awakening for many economists. It became increasingly apparent that the basic Keynesian framework was not the appropriate vehicle for understanding what happens during a business cycle nor did it seem capable of providing the empirically correct answers to questions involving changes in the economic environment or changes in monetary or fiscal policy. The view that Keynesian economics was an empirical success even if it lacked sound theoretical foundations could no longer be taken seriously.

The essential flaw in the Keynesian interpretation of macroeconomic phe nomenon was the absence of a consistent foundation based on the choice theoretic framework of microeconomics. Two important papers, one by Milton Friedman (1968) and the other by Robert Lucas (1976), forcefully demonstrated examples of this flaw in critical aspects of the Keynesian reasoning and set the stage for modern macroeconomics.

A central feature of the Keynesian system of the 1960s was the tradeoff between inflation and some measure of real output or unemployment. Friedman argued that basic microeconomic principles demanded that this long run Phillips curve must be vertical. That is, general microeconomic principles implied that individuals (firms) maximizing their utility (profit) resulted in real demand (and supply) curves that are homogeneous of degree zero in nominal prices and money income. Thus sustained inflation was compatible with any level of real demand (or supply) of goods. A central Keynesian tenet was therefore in stark conflict with microeconomic principles. 1

چارچوب اصلی چرخه کسب و کار واقعی

مدل نوکلاسیک از انباشت سرمایه

بازده تعادل

واکنشها به اختلالات بهرهوری

عرضه یا تقاضا

مدلهای تصادفی و عدم قطعیت

رشد اقتصادی و چرخههای کسب و کار

چرخههای کسب و کار واقعی و اقتصاد ایالات متحده در سالهای 1985-1954

خلاصه آمار اقتصاد ایالات متحده

تغییرات بهرهوری

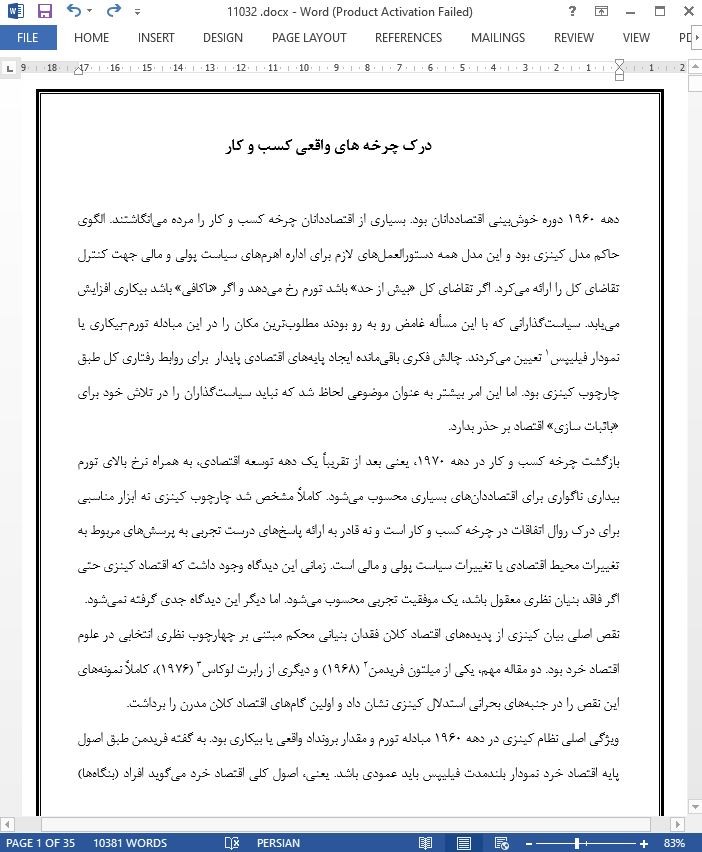

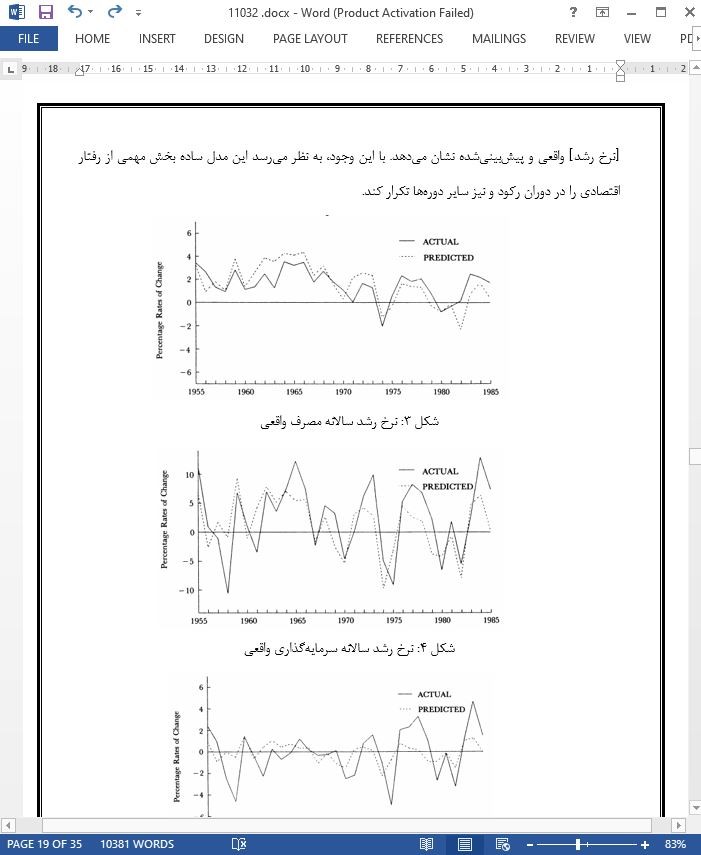

چرخههای کسب و کار واقعی

سیاستهای دولت و تعادل غیر بهینه

برنامه پژوهشی چرخه کسب و کار واقعی

گسترش چندبخشی

بازارهای نیروی کار

رشد درونی

پول

راهبردهایی برای تخمین و آزمون فرضیه

نتیجهگیری

The Basic Real Business Cycle Framework

The Neoclassical Model of Capital Accumulation

Equilibrium Outcomes

Responses to Productivity Disturbances

Supply or Demand

Stochastic Models and Uncertainty

Economic Growth and Business Cycles

Real Business Cycles and the 1954-1985 U.S. Economy

Summary Statistics for the U.S. Economy

Productivity Shifts

Real Business Cycles

Government Policies and Suboptimal Equilibrium

The Real Business Cycle Research Agenda

Multi-Sector Extensions

Labor Markets

Endogenous Growth

Money

Strategies for Estimation and Hypothesis Testing

Conclusions

- اصل مقاله انگلیسی با فرمت ورد (word) با قابلیت ویرایش

- ترجمه فارسی مقاله با فرمت ورد (word) با قابلیت ویرایش، بدون آرم سایت ای ترجمه

- ترجمه فارسی مقاله با فرمت pdf، بدون آرم سایت ای ترجمه