دانلود رایگان مقاله زمانبندی گلدهی

آغاز گلدهی، یک نشان حیاتی از تاریخچه حيات است؛ گیاهان، در یک زمان از سال که موفقیت باروری حداکثر را در یک حوزه معین تضمین می کند، تکامل می یابند. چند دهه از مطالعات فیزیولوژیکی نشان داده است که گلدهی در پاسخ به نشانه های زیست محیطی و مسیرهای داخلی آغاز می شود. نشانه های زیست محیطی معمول مورد مطالعه عبارتند از: تغییر در دما و طول روز. مسیرهای درون زا به طور مستقل از سیگنال های زیست محیطی عمل می کنند و به حالت رشد و نمو گیاه مربوط می شوند؛ چنین مسیرهایی، گاهی اوقات به عنوان مسیرهای "مستقل" مورد اشاره قرار می گیرند که نشان دهنده عدم نفوذ زیست محیطی است. سهم نسبی ورودی های مستقل و زیست محیطی برای "تصمیم" گلدهی در میان گونه های مختلف متفاوت است. برای مثال، گلدهی به طور کامل ناشی از مسیرهای مستقل در انواع توتون و تنباکو در نظر گرفته می شود (Tabacum Nicotiana) که تعداد ثابتی از گره ها را تشکیل می دهند، بدون در نظر گرفتن محیطی که قبل از گلدهی در آن رشد کرده است (McDaniel و Hsu ،1976 ). با این حال، تغییر تک ژنی ممکن است سبب شود که توتون و تنباکو نیاز به روزهای کوتاهی برای گلدهی داشته باشند (Allard 1919) ، که نشان می دهد که تفاوت های بیوشیمیایی اساسی بین حس کردن-محیط زیست و معابر درون زا می توانند حداقل باشد. همچنین، مسیرهای درون زا و زیست محیطی می توانند با یکدیگر تعامل داشته باشند. به عنوان مثال، برخی از گیاهان از یک فاز نوجوان عبور می کنند که در آن، آنها به نشانه های محیطی که گلدهی را ارتقا می دهند پاسخ نمی دهند (Poethig، 1990)؛ یعنی گذار از فاز نوجوان به بالغ، نوعی از مسیر درون زا است که برای ارائه صلاحیت در مسیرهای زیست محیطی برای ارتقای گلدهی ضروری است. اضافه شدن ژنتیک مولکولی به طیف وسیعی از روش های مورد استفاده برای مطالعه شروع گلدهی در همین اواخر، برخی از بینش های مولکولی را به مسیرهای درونزا و حسگر-زیست محیطی ارائه نموده است و نشان داده است که چگونه ورودی ها از مسیرهای مختلف در تصمیم گلدهی یکپارچه می شوند.

(با توجه به تلاش های مستمر بسیاری از دانشمندان که روی بسیاری از گونه ها مشغول کار هستند، ما مطالب بسیاری در مورد زمان گلدهی یاد گرفته ایم که ارزشمند است. متاسفانه، به دلیل محدودیت های زمانی و مراجع، تنها بخش کوچکی از این بدنه گسترده از کارها را می توان در این مقاله پوشش داد. بر این اساس، ما اغلب خوانندگان را برای بحث عمیق تر به مقالات بررسی های اخیر ارجاع می دهیم و از همکارانی که کارشان با توجه به این محدودیت ها ذکر نشده است عذرخواهی می کنیم.)

واکنش نوری و هورمون گلدهی: یک مسیر قدیمی

نوسانات سالانه در طول روز که در سطح سیاره ما زیاد رخ می دهد، یک نشانه زیست محیطی قابل اعتماد را در مورد زمانی از سال ارائه می دهد. بنابراین، تعجب آور نیست که مسیرهایی که گلدهی را در پاسخ به فتوپريود آشکار می سازند و ارتقا می دهند، قدیمی ترین و حفاظت شده ترین مسیرها هستند. آزمایش های فیزیولوژیکی انجام شده برای اولین بار در دهه 1930 (Knott، 1934) نشان داد که فتوپريودهاي القائی توسط برگ ها احساس می شوند. این، دو سؤال اساسی را مطرح می کند: چگونه برگ ها می توانند طول روز را اندازه گیری کنند و ماهیت سیگنال گلدهی (معروف به florigen) چیست که از برگ به بافت جنینی راس جوانه، گذار خواهد داشت؟ پس از هفت دهه پژوهش، ما در حال حاضر پاسخ نسبتا روشن و رضایت بخشی به این پرسش ها، به خصوص در مورد Arabidopsis داریم (Arabidopsis thaliana).

Arabidopsis در مقایسه با روزهای کوتاه، با سرعت بیشتری در روزهای طولانی گل می دهد و در نتیجه یک گیاه سازگار با طول روز است. تنظیم CONSTANS ارتقا دهنده گلدهی (CO)، کلیدی در درک روزهای طولانی القايي است (Turck و همکاران، 2008). ساعت شبانه روز، رونویسی CO را تنظیم می کند به طوری که اوج ظهور در روزهای بلند، در اواخر روز رخ می دهد اما پس از غروب در روزهای کوتاه (Suarez-Lopez و همکاران، 2001). پروتئین CO، به نوبه خود، توسط نور تثبیت می شود و به سرعت در تاریکی تخریب می شود (Valverde و همکاران، 2004). در نتیجه، پروتئین CO تنها می تواند در طول روزهای طولانی تجمع یابد. CO در عروق برگ ظاهر می شود، و نقش آن در گل، فعال کردن ظهور FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) است که یک پروتئین کوچک را کدگذاری می کند که هورمون گلدهی است (شکل 1). در برنج (Oryza sativa) و Arabidopsis، FT یک ارتقا دهنده قوی گلدهی است که از عروق برگ به بافت جنینی نوک انتقال می یابد (Tamaki و همکاران، 2007 Corbesier و همکاران، 2007). در بافت جنینی، FT به شکل یک مجموعه با فاکتور رونویسی FD bZIP است و گلدهی با فعال نمودن ژن های هویت بافت جنینی گل مانند APETALA1 و دیگر ارتقادهنده های گل مانند SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS1 ( SOC1؛ Michaels ، 2009) آغاز می شود. بنابراین، تنظیم FT در پایان یک مسیر حس کننده-زیست محیطی نهفته است و رشد گل را آغاز می کند. علاوه بر مسیر فتوپریودی، FT و SOC1 نیز توسط دیگر مسیرهای گلدهی تنظیم می شوند (به عنوان مثال تسریع رشد گیاهان در دماهای سرد؛ قسمت زیر را ببینید) و بنابراین به عنوان یکپارچه کننده های گل به آنها اشاره می شود.

به نظر می رسد جفت شدن CO و FT یک ماژول باستانی و از نظر تکاملی سازگار باشد. بر خلاف وضعیت Arabidopsis، که در آن روزهای طولانی منجر به فعال سازیCO و القای FT می شود، هومولوگ های Co/FT برنج (HEADING DATE1/HEADING DATE3A) دارای مسیرهای مختلف تکاملی هستند که در پاسخ به روزهای کوتاه باعث گلدهی می شود ( Turckو همکاران، 2008). بررسی نقش احتمالی CO و FT در انواع واکنش فتوپریودی پیچیده تر، مانند گونه های مختلف Bryophyllum، که بعد از روزهای کوتاه برای گلدهی نیاز به روزهای بلند دارد جالب می باشد (یعنی گیاهان نگهداشته شده تحت روزهای ثابت طولانی یا کوتاه، گل نمی دهند). همچنین شواهدی وجود دارد که نقش CO و FT فراتر از گلدهی گسترش می یابد. در درختان صنوبر (صنوبر SPP.)، CO و FT در شروع خواب وابسته به فتوپریود (Turck و همکاران، 2008) نقش دارند. همچنین اطلاعات جذابی وجود دارد که نشان می دهد که استفاده از دی اکسید کربن به عنوان یک شاخص طول روز ممکن است گیاهان گلدار را در دام بیاندازد . Chlamydomonas reinhardtii فاقد FT است اما حاوی یک ژن CO مانند ( CrCO ) نیز نمی باشد که خروجی ساعت شبانه روزی است؛ شایان ذکر است که CrCO تا حدی می تواند جهش های همزمان را در Arabidopsis (Serrano و همکاران، 2009.) نجات دهد. با توجه به این که CO در یک خانواده نسبتا بزرگ ژن (17 ژن CO مانند در Arabidopsis ) وجود دارد، این امکان وجود دارد که ژن های مربوط به CO، نقش های اضافی را در پاسخ های گیاه به طول روز ایفا نمایند که این نقش ها باید کشف شود.

تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد

تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد به عنوان فرایندی تعریف می شود که در آن مواجهه با سرمای زمستان گیاهان را به طور شایسته به گلدهی می رساند (Kim و همکاران، 2009). عبور از زمستان یک نشانه زیست محیطی است که هنگامی که با حس کردن طول روز همراه می شود، اطلاعات شفاف فصلی را فراهم می کند که فصول بهار و پاییز را متمایز می کند. برای سرما به عنوان یک نشانه قابل اعتماد برای زمستان، گیاهان باید قادر باشند تا مشخصه مواجهه طولانی سرمای زمستان را که ممکن است به عنوان مثال در پاییز رخ دهند از نوسانات کوتاه دمایی تشخیص دهند. بنابراین، تعجب آور نیست که تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد (و در بسیاری از گونه ها، شکستن خواب جوانه) نیاز به مواجهه با سرمای طولانی مدت دارد. نیاز به تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد اغلب در گیاهان زمستان سالانه و دوسالانه یافت می شود که در اوایل بهار گل می دهند؛ این گیاهان معمولا در پاییز ایجاد می شوند، و نیاز به تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد تضمین می کند که گلدهی زودرس در فاز استقرار پاییز رخ نمی دهد.

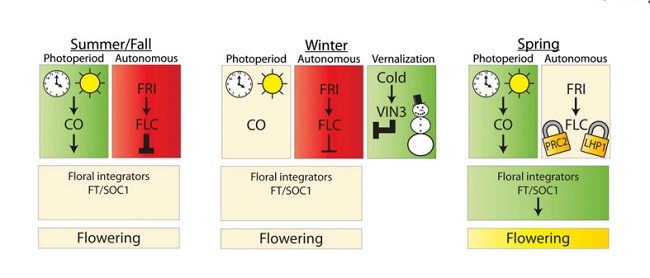

در Arabidopsis سالانه در فصل زمستان، بلوک پاسخگوی- تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد برای گلدهی نیاز به تعامل دو ژن دارد، FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) و FRIGIDA (FRI; Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999; Johanson et al., 2000).. FLC یک فاکتور رونویسی حاوی دامنه MADS است که به عنوان یک سرکوب کننده گلدهی عمل می کند، و FRI ژن گیاهی خاص برای عملکرد بیوشیمیایی ناشناخته است که برای سطوح بالایی از بیان FLC مورد نیاز است. FLC به طور مستقیم با سرکوب مروج های کلیدی گلدهی،FT ، SOC1 ، و FD مانع از گلدهی می شود (Michaels، 2009؛ شکل 1). تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد، گلدهی را در روزهای طویل فصل بهار به سرعت از طریق سرکوب FLC برای گیاهان سمیسر می سازد (شکل 1). FRI و FLC برای اولین بار از نظر ژنتیکی در تلاقی های بین زمستان-سالانه و چرخه-سریع شناسایی شدند (Napp-Zinn, 1979; Burn et al., 1993; Lee et al., 1993; Clarke and Dean, 1994; Gazzani et al., 2003; Michaels et al., 2003) . سالانه های زمستان شامل ژن های ناهمسان مجاور عملکردی برای هر دو ژن می شود، در حالی که الحاق چرخه-سریع شامل جهش های افت/کاهش عملکرد در هر دو FRI یا FLC می شود ( Kim و همکاران، 2009). بنابراین، الحاق چرخه-سریع از سالانه های زمستان با تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد توسط تعامل FRI و FLC تکامل می یابد.

پس از اینکه زمستان گذشت، یک "حافظه" دائم از فصل زمستان در بسیاری از گونه های گیاهی وجود دارد (یعنی حالت تسریع شده رشد گیاه در دمای سرد، در طی رشد بعدی و تقسیم سلولی میتوزی پایدار است). ثبات میتوزی در غیاب سیگنال القاکننده (سرد) یک تعریف کلاسیک از یک تغییر اپی ژنتیک حالت است (Amasino، 2004). در Arabidopsis، ماهیت اپی ژنتیک حالت تسریع شده رشد گیاه در دمای سرد از یک سری از تغییرات برای کروماتین FLC حاصل می شود که نتیجه آن از نظر تقسیم سلولی، سرکوب پایدار است. به طور خاص، سطوح دو تغییر سرکوبگر، trimethylation Histone H3 در Lys -9 (H3K9) و Lys -27 (H3K27)، در کروماتین FLC در طول و پس از مواجهه با سرما افزایش می یابد ( Bastow و همکاران، 2004 ؛ song وAmasino ، 2004 ). متیلاسیون H3K27 در FLC، منجر به فعالیت سرکوبگر Polycomb می شود Complex2 (PRC2) که برای اولین بار در حیوانات شناخته شده است و در یوکاریوت ها (Kim و همکاران، 2009) حفظ شده است. در طی مواجهه سرما، VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE3 (VIN3)، ژن کد کننده یک جزء خاص گیاه از مجموعه PRC2 که برای سرکوب FLC ضروری است، القا می شود ( Wood و همکاران، 2006 ؛ De Losia و همکاران، 2008). مجموعه PRC2 در گیاهان و حیوانات در سرکوب تعداد زیادی از ژن ها درگیر می شوند، اما در Arabidopsis ، VIN3 ناشی از سرما، یک جزء خاص برای روند تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد است؛ بنابراین، نسخه VIN3 حاوی PRC2، به احتمال زیاد یک زیر مجموعه خاص از ژن های تسریع رشد گیاه در سرما را هدف قرار می دهد. یک خانواده از از ژن های VIN3 مانند در Arabidopsis (Kim و همکاران، 2009) وجود دارد، و به این دلیل که VIN3 به طور خاص برای خاموش کردن واسطه-تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد FLC حیاتی است، یک موضوع جذاب برای حل و فصل نمودن می باشد. جالب توجه است که در هنگام مواجهه با سرما، یک افزایش گذرا در بیان غیررمزگذاری RNA مکمل برای FLC معروف به COOLAIR ( Swiezewskiو همکاران، 2009) وجود دارد، اما باید مشخص شود که چه نقشی را در صورت وجود، این RNA در سرکوب نمودن FLC واسطه-تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد بازی می کند.

The initiation of flowering is a critical life-history trait; plants have presumably evolved to flower at a time of year that ensures maximal reproductive success in a given region. Decades of physiological studies have revealed that flowering is initiated in response to both environmental cues and endogenous pathways. Commonly studied environmental cues include changes in temperature and daylength. Endogenous pathways function independently of environmental signals and are related to the developmental state of the plant; such pathways are sometimes referred to as “autonomous” to indicate the lack of environmental influence. The relative contributions of autonomous and environmental inputs to the flowering “decision” vary among, and even within, species. For example, flowering is considered entirely due to autonomous pathways in a variety of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) that forms a fixed number of nodes before flowering regardless of the environment in which it is grown (McDaniel and Hsu, 1976). Yet, a single-gene change can cause tobacco to require short days to flower (Allard, 1919), which indicates that the underlying biochemical differences between environment-sensing and endogenous pathways can be minimal. Also, endogenous and environmental pathways can interact. For example, some plants pass through a juvenile phase in which they are not responsive to environmental cues that promote flowering (Poethig, 1990); that is, the transition from the juvenile to adult phase is a type of endogenous pathway that is necessary to provide competence for environmental pathways to promote flowering. The recent addition of molecular genetics to the range of approaches used to study the initiation of flowering has provided some molecular insights into these endogenous and environmentsensing pathways and has revealed how inputs from multiple pathways are integrated into the flowering decision.

(Due to the sustained efforts of a multitude of scientists working in many species, we have learned much about the timing of flowering that is worth celebrating. Unfortunately, only a small part of this extensive body of work can be covered in this article because of length and reference limits. Accordingly,we frequently refer readers to recent review articles for more in-depth discussions, and we apologize to our colleagues whose work was not cited due to these constraints.)

PHOTOPERIODISM AND FLORIGEN: AN ANCIENT PATHWAY

The annual fluctuations in daylength that occur over much of the surface of our planet provide a reliable environmental cue regarding the time of year. It is not surprising, therefore, that the pathways that detect and promote flowering in response to photoperiod are among the most ancient and conserved. Physiological experiments first done in the 1930s (Knott, 1934) demonstrated that inductive photoperiods are sensed by leaves. This raised two fundamental questions: how do leaves measure daylength, and what is the nature of the flowering signal (known as florigen) that must travel from the leaves to the shoot apical meristem? After another seven decades of research, we now have relatively clear and satisfying answers to these questions, especially in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana).

Arabidopsis flowers more rapidly in long days than in short days and is thus a facultative long-day plant. The regulation of the floral promoter CONSTANS (CO) is key in the perception of inductive long days (Turck et al., 2008). The circadian clock regulates CO transcription such that peak expression occurs late in the day in long days but after dusk in short days (Suarez-Lopez et al., 2001). CO protein, in turn, is stabilized by light and rapidly degraded in darkness (Valverde et al., 2004). As a result, CO protein can only accumulate during inductive long days. CO is expressed in the vasculature of leaves, and its role in flowering is to activate the expression of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), which encodes a small protein that is florigen (Fig. 1). In both rice (Oryza sativa) and Arabidopsis, FT is a strong promoter of flowering that is translocated from the vasculature of leaves to the shoot apical meristem (Corbesier et al., 2007; Tamaki et al., 2007). In the meristem, FT forms a complex with the bZIP transcription factor FD and initiates flowering by activating floral meristem-identity genes such as APETALA1 and other floral promoters such as SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS1 (SOC1; Michaels, 2009). Thus, FT up-regulation lies at the end of an environment-sensing pathway and initiates flower development. In addition to the photoperiod pathway, FT and SOC1 are also regulated by other flowering pathways (e.g. vernalization; see below) and therefore are referred to as floral integrators.

The coupling of CO and FT appears to be an ancient and evolutionarily adaptable module. Unlike the situation in Arabidopsis, in which long days lead to CO activation and FT induction, the rice CO/FT homologs (HEADING DATE1/HEADING DATE3A) have evolved different circuitry that triggers flowering in response to short days (Turck et al., 2008). It will be interesting to explore the possible role of CO and FT in more complex photoperiod response types, such as various species of Bryophyllum, which require long days followed by short days for flowering to occur (i.e. plants maintained under constant long or short days do not flower). There is also evidence that the role of CO and FT extends beyond flowering. In poplar (Populus spp.) trees, CO and FT are involved in the initiation of photoperiod-dependent dormancy (Turck et al., 2008). There is also intriguing data demonstrating that the use of CO as a daylength indicator may predate flowering plants. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii lacks FT but does contain a CO-like gene (CrCO) that is an output of the circadian clock; remarkably, CrCO can partially rescue co mutants in Arabidopsis (Serrano et al., 2009). Given that CO exists in a relatively large gene family (17 CO-like genes in Arabidopsis), it is possible that CO-related genes play additional yet-tobe-discovered roles in plant responses to daylength.

VERNALIZATION

Vernalization is defined as the process by which exposure to the cold of winter renders plants competent to flower (Kim et al., 2009). The passage of winter is an environmental cue that, when coupled to photoperiod sensing, provides clear seasonal information that distinguishes the spring and fall seasons. For cold to be a reliable cue for winter, plants need to be able to distinguish the long cold exposure characteristic of winter from short fluctuations in temperature that might occur, for example, in the fall. Thus, it is not surprising that vernalization (and in many species the breaking of bud dormancy) requires exposure to prolonged cold. A vernalization requirement is often found in winter-annual and biennial plants that flower early in the spring; these plants typically become established in the fall, and a vernalization requirement ensures that premature flowering does not occur during the fall establishment phase.

In winter-annual Arabidopsis, the vernalizationresponsive block to flowering requires the interaction of two genes, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) and FRIGIDA (FRI; Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999; Johanson et al., 2000). FLC is a MADS domain-containing transcription factor that acts as a floral repressor, and FRI is a plant-specific gene of unknown biochemical function that is required for high levels of FLC expression. FLC inhibits flowering by directly repressing the key promoters of flowering, FT, SOC1, and FD (Michaels, 2009; Fig. 1). Vernalization permits plants to flower rapidly in the lengthening days of spring through repression of FLC (Fig. 1). FRI and FLC were first identified genetically in crosses between winter-annual and rapid-cycling accessions (Napp-Zinn, 1979; Burn et al., 1993; Lee et al., 1993; Clarke and Dean, 1994; Gazzani et al., 2003; Michaels et al., 2003); winter annuals contain functional alleles of both genes, whereas rapid-cycling accessions contain loss-/reduction-of-function mutations in either FRI or FLC (Kim et al., 2009). Thus, rapid-cycling accessions evolved from winter annuals by shedding the vernalization requirement conferred by the interaction of FRI and FLC.

After winter has passed, there is a permanent “memory” of winter in many plant species (i.e. the vernalized state is stable during subsequent growth and mitotic cell division). Mitotic stability in the absence of the inducing signal (cold) is a classic definition of an epigenetic change of state (Amasino, 2004). In Arabidopsis, the epigenetic nature of the vernalized state results from a series of modifications to FLC chromatin that result in mitotically stable repression. Specifically, the levels of two repressive modifications, trimethylation of histone H3 at Lys-9 (H3K9) and Lys27 (H3K27), increase at FLC chromatin during and after cold exposure (Bastow et al., 2004; Sung and Amasino, 2004). H3K27 methylation at FLC results from the activity of Polycomb Repressive Complex2 (PRC2), which was first identified in animals and is conserved in eukaryotes (Kim et al., 2009). During cold exposure, VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE3 (VIN3), a gene encoding a plant-specific component of the PRC2 complex that is essential for FLC repression, is induced (Wood et al., 2006; De Lucia et al., 2008). The PRC2 complex in plants and animals is involved in the repression of a large number of genes, but in Arabidopsis, the cold-induced VIN3 is a component specific for the vernalization process; thus, the VIN3-containing version of PRC2 is likely to target a vernalizationspecific subset of genes. There is a family of VIN3-like genes in Arabidopsis (Kim et al., 2009), and why VIN3 is specifically critical for vernalization-mediated silencing of FLC is an intriguing issue to resolve. It is also intriguing that during cold exposure, there is a transient increase in expression of a noncoding RNA complementary to FLC known as COOLAIR (Swiezewski et al., 2009), but it remains to be determined what role, if any, this RNA plays in vernalization-mediated FLC silencing.

واکنش نوری و هورمون گلدهی: یک مسیر قدیمی

تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد

کنترل مستقل گلدهی

ادغام فتوپریود و تسریع رشد گیاه با قرار گرفتن در دماهای سرد

PHOTOPERIODISM AND FLORIGEN: AN ANCIENT PATHWAY VERNALIZATION

AUTONOMOUS CONTROL OF FLOWERING

VERNALIZATION

IN TEGRATION OF PHOTOPERIOD AND VERNALIZATION