دانلود رایگان مقاله بررسی خواص روان کارهای افشانشی در فرایند ریخته گری تحت فشار

چکیده

در حین فرایند ریختهگری تحتفشار، روانکار برای خنک کردن قالب ها و تسهیل خروج قطعه در قسمت درونی قالب پاشیده میشود. اثرات خنک کاری روانکار قالب، با استفاده از آنالیز توزین حرارتی (TGA)، حسگرهای شار حرارتی (HFS) و تصویربرداری مادونقرمز مورد بررسی قرار گرفتند. سیر تکاملی شار حرارتی و تصاویر گرفتهشده توسط دوربین مادونقرمز سرعتبالا نشان دادند که اعمال روان کار یک فرایند کوتاه و گذرا می باشد. زمان پاسخدهی کوتاه حسگرهای HFS نظارت و فراگیری داده های حرارت سطحی و شار حرارتی را بدون نیاز به پردازش داده های اضافی امکانپذیر میسازد. مجموعه ی مشابهی از آزمایشها با استفاده از آب دیونیزه نیز برای ارزیابی اثر روانکار انجام داده شد. شار حرارتی بالای بهدستآمده در C° 300 به خواص ترکنندگی و جذب روان کار نسبت داده شد. تصاویر مربوط به مخروط پاشش و جریان روانکار بر روی قالب نیز برای توضیح تکامل شار حرارتی مورد استفاده قرار گرفتند.

1. مقدمه

در فرایند ریخته گری تحتفشار، قالب ها با روان کار پاشیده شده، بسته شده و فلز مذاب درون آن ها با فشار بالایی تزریق می شود. قطعات با شکل اصلی پس از انجماد و سرد شدن فلز به دست آمده، قالب ها باز شده و قطعات خارج می شوند. روان کارها خروج قطعات نهایی را تسهیل بخشیده، اثر چسبندگی را کاهش داده (Fraser and Jahedi, 1997) و قالب ها را سرد می کند (Piskoti, 2003). ضخامت لایه روان کار بر روی قالب برای کمَی کردن عملکرد چسبندگی روان کار مورد استفاده قرار گرفته شد. ضخامت لایه روان کار معمولاً به صورت غیرمستقیم و با استفاده از روش چشمی یا اشعه ایکس (Fraser and Jahedi, 1997) و یا حرارت قالب اندازه گیری می شود (Piskoti, 2003). کانال هایی درون قالب ها برای گرم یا سرد کردن حفر می شوند. این کانال ها دما را طوری کنترل می کنند که انجماد به صورت تدریجی و سرد شدن بهطور یکنواخت انجام شود. بهمنظور حداقل ساختن عیوب ریخته گری، ریختن فلز مذاب و سیستم گرمایشی/سرمایشی بر اساس آنالیز انتقال حرارت و پدیده انجماد طراحی شده اند. یکی از پارامترهای موردنیاز برای طراحی قالب، مقدار حرارت خروجی طی اعمال روان کار می باشد. داده های ضریب انتقال حرارت یا تغییرات شار حرارتی در حین عملیات روان کاری برای بررسی قابلیت روان کار در خارج کردن حرارت و برای انجام شبیه سازی های عددی فرایند ریخته گری تحتفشار استفاده می شوند (Liu et al., 2000).

خنک کاری توسط افشانش در کاربردهای دیگری بهغیراز ریخته گری تحتفشار مورد بررسی قرار گرفته است. در مطالعه ی برخورد ذرات اسپری برای قطعات الکترونیکی قدرتی با استفاده از آب و مبرد و همچنان در صنایع فولاد با استفاده از آب و روغنها تلاش قابل توجهی شده است (Stewart et al., 1995). به غیر از مدل های مربوط به شار حرارتی بحرانی (CHF)، مدل های اندکی برای پیشگویی انتقال حرارت وجود دارند (Pautsch and Shedd, 2005). یک مدل CHF که نرخ شار حجمی، خواص سیال، زاویه پاشش، قطر قطرات و تحت تبرید را محاسبه می کند توسط مداوار و استس پیشنهاد شده است (Medawar and Estes, 1996). سیه و همکاران al., 2004a) (Hsieh et روابطی برای شار حرارتی خروجی، تابع پارامترهای بی بعدی مثل شماره قطره وبر و عدد جیکوب مایع برای فوق گدازهای کم ارائه دادند. بااینکه این اطلاعات می تواند برای فرمولبندی روان کارهای جدید مفید باشد، اما استفاده از این روابط برای جوشش، قطرات کوچک و یا اسپری های آبی که برای فرایندهای دیگر طراحی شده اند دشوار و یا حتی غیرممکن می باشد. به عنوان مثال، جوشش قطرات کوچکی که بر روی سطح داغی قرار داده شده اند با جوشیدن قطراتی درون یک استخر متفاوت است زیرا انتقال حرارت به منطقه ی تماسی بین قطرات و سطوح وابسته می باشد (Cui etal., 2003). روابط به دست آمده در مطالعات برخورد ذرات اسپری برای فرایند اعمال روان کار کاربرد ندارند زیرا بین این دو فرایند تفاوت های زیادی وجود دارد. این تفاوتها شامل موارد زیر می شوند:

• فوق گداز متفاوت: در فرایند ریخته گری تحتفشار، فوق گداز بین 150 تا C°400 می باشد، درحالیکه در وسایل الکترونیکی قدرتی و در سریع سرد کردن فولاد فوق گداز به ترتیب 150 و C°1100 می باشد؛

• مواد سطحی متفاوت؛

• نرخ های شار متفاوت؛

• گذرا و یا یکنواخت بودن: بیشتر مطالعات انجام شده بر فرایندهای به جوش آمدن در حالت یکنواخت می-باشند، درحالیکه روانکاری قالب، فرایندی بسیار گذرا است که بین 2/0 الی چند ثانیه طول میکشد.

در حالت جوشش پایدار سه منطقه متفاوت وجود دارد: همرفت و تبخیر اجباری، جوشش هسته ای و شار حرارتی بحرانی؛ درحالیکه در سرمایش گذرا جوشش فیلمی و جوشش گذرا نقش مهمی ایفا می کنند (Hsieh et al.,2004b). گنزالز و بلک (Gonzalez and Black, 1997) کشف کردند که اندرکنش بین اسپری و جت شناور که از سطح گرمی صادر شود باعث کاهش سرعت قطره خواهد شد.

روش اصل اول که در صنایع دیگر برای تحقیقات سرمایش اسپری مورد استفاده قرار گرفته شده بود، برای بررسی پدیده اصلی و بررسی اثرات پارامترهای مختلف مفید بوده ولی پیاده سازی آن در یک محیط دستگاهی دشوار خواهد بود. جدیداً، روش های دیگری مانند تصویرسازی برای مطالعه سرمایش اسپری مورد استفاده قرار گرفته شده است. برای فوق گدازهای کم، ردیفی از گرمکنندههایی در اندازه ی میکرو که به صورت جداگانه کنترلشده و بر روی زیر لایه ای شفاف و سیلیکونی قرار گرفته شدند مورد استفاده قرار گرفته شد (Horacek et al., 2005). فاصله فضایی شار حرارتی در دمای سطحی ثابت به دست آمد و تصویرسازی و اندازه گیری ناحیه تماس مایع-جامد و طول خط تماس سه فاز با استفاده از یک روش بازتابی درونی انجام گردید (Horacek et al., 2005). اندرکنش بین روان کار پودری و آلیاژ مذاب با استفاده از یک سیستم پرسرعت ویدیویی مشاهده گردید (Kimura et al., 2002). نتایج مشاهدات درجا نشان دادند که تبخیر موم موجود در روان کار باعث تشکیل یک فیلم نازک گازی بین آلیاژ مذاب و قالب شده که توانایی عایقبندی را بهبود داده است.

در بیشتر مطالعات مربوط به اثرات اعمال روان کار، سیستمی دارای صفحات گرم شده که درواقع شبیهسازیشدهی قالب های ریخته گری تحتفشار می باشد، مورد استفاده قرار گرفته و داده های دمایی با استفاده از ترموکوپل هایی که درون این صفحات جایگذاری شده اند جمع آوری می شوند (Lee et al., 1989; Garrow, 2001). ضریب های انتقال حرارت (یا شارهای حرارتی) با استفاده از برون یابی ساده داده ها یا فرایند انتقال حرارت معکوس به دست می آیند. در برخی از این مطالعات، داده ها در فرکانس های کم ثبت شدند؛ بهعنوانمثال، در تحقیق لیو، فقط دو داده بر ثانیه ثبت گشتند (Liu et al., 2000). به علت تأخیر زمان پاسخ ترموکوپل، این امکان وجود دارد که داده های دمایی با دمای واقعی بسیار متفاوت باشد. برای جلوگیری از آنالیز سنگین داده ها، مثلاً انجام آنالیز انتقال حرارت معکوس و یا در نظر گرفتن زمان پاسخ ترموکوپل (Reichelt et al., 2002)، سابو و وو (Sabau and Wu, 2007) از حس گر برای اندازه گیری مستقیم شار حرارتی استفاده کردند. علاوه بر داده های مربوط به شار حرارتی، حس گر، داده های مربوط به دمای سطح را نیز ارائه می دهد که محاسبه ضریب انتقال حرارت را امکان پذیر می سازد. توزیع دمایی شار حرارتی متوسط اسپری های آبی، که توسط سابوو و وو(Sabau and Wu, 2007) ارائه گشت، مشابه با نتایج بهدستآمده با استفاده از منحنی جوش استخری بوده است. این امر استفاده از حسگرهای یادشده را برای اندازه گیری مستقیم شار حرارتی در شرایط خاص ریخته گری تحتفشار تائید می کند.

در این تحقیق، با استفاده و تکمیل روش اصل اول نحوه ی کار روان کار توصیف می گردد. رفتار روان کار توسط آنالیز توزین حرارتی، حسگرهای شار حرارتی (HFS) و تصویربرداری مادونقرمز بررسی گشت؛ از روان کار Diluco 135TM که توسط شرکت Cross Chemical Company, Inc تأمین گردید استفاده شد. این روان کار Diluco برای قطعات ریختگی منیزیم ساختهشده است. بر اساس معلومات شرکت سازنده، در تولید این روان کار از روغن های تصفیهشده، پلیمرهای طبیعی و مصنوعی، موم های طبیعی و مصنوعی، عوامل تر کننده و عوامل امولسیون کننده برای تسهیل خروج قطعات از قالب استفاده شده است. نسبت رقت 15:1 برای مخلوط روان-کار:آب توسط سازنده توصیه شده است.

در قسمت دوم، آنالیز توزین حرارتی آنالیز حرارتی افتراقی برای تعیین ویژگی های تجزیه شدن روان کار استفاده گردید زیرا این ویژگیهای روانکار برای تعیین کارایی آن و کیفیت قطعه ریختگی اهمیت دارند. بهعنوانمثال، اگر روانکار سریعاً و در دمای کم تبخیر شود، فلز مذاب در تماس مستقیم با قالب قرار گرفته و درواقع روان کار وظیفه خود را انجام نخواهد داد. از طرف دیگر، اگر اتمسفر موجود در حفره قالب دارای مقدار قابلتوجهی محصولات تجزیهشده ی فرار باشد، احتمال حبس شدن گاز درون فلز مذاب افزایش یافته که باعث افزایش عیوب گشته و کیفیت قطعه را کاهش خواهد داد. در قسمت سوم، نتایج شار حرارتی و دمای سطحی که با استفاده از حسگر شار حرارتی اندازه گیری شدند، ارائه شده است. در طی آزمایش، فاصله بین نازل اسپری و صفحه ثابت نگه داشته شد.

Abstract

During the high pressure die casting process, lubricants are sprayed in order to cool the dies and facilitate the ejection of the casting. The cooling effects of the die lubricant were investigated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), heat flux sensors (HFS), and infrared imaging. The evolution of the heat flux and pictures taken using a high-speed infrared camera revealed that lubricant application was a transient process. The short time response of the HFS allows the monitoring and data acquisition of the surface temperature and heat flux without additional data processing. A similar set of experiments was performed with deionized water in order to assess the lubricant effect. The high heat flux obtained at 300 ◦C was attributed to the wetting and absorbent properties of the lubricant. Pictures of the spray cone and lubricant flow on the die were also used to explain the heat flux evolution.

1. Introduction

During the die casting process, the dies are sprayed with a lubricant, dies are closed, and liquid metal is injected into the die cavity under high pressures. Net shape parts are produced after subsequent metal solidification and cooling, dies are opened, and parts are ejected. Lubricants facilitate the ejection of the finished product, reduce the soldering effects (Fraser and Jahedi, 1997), and cool the dies (Piskoti, 2003). The lubricant film thickness on the die surface was used to quantify the lubricant adhesion performance. The lubricant film thickness was usually determined indirectly, using optical or X-ray techniques (Fraser and Jahedi, 1997) or die temperature (Piskoti, 2003). Channels are drilled into the dies for heating or cooling in order to maintain temperature levels that will yield progressive solidification and uniform cooling of the parts. In order to minimize casting defects, the metal delivery and heating/cooling systems are designed based on the analysis of heat transfer and solidification phenomena. One of the parameters required for the die design is the amount of heat removed during lubricant application. Data on heat transfer coefficients or heat flux evolution during lubricant application are used to characterize the heat removal capability of lubricants and perform numerical simulations of the die casting process (Liu et al., 2000).

Spray cooling was mainly studied for other applications than the die casting process. There is significant effort on the study of spray impingement for power electronics using water and refrigerants, and steel industry using water and oils (Stewart et al., 1995). Few predictive models for heat transfer exist other than those for critical heat flux (CHF) (Pautsch and Shedd, 2005). A CHF correlation that accounts for volumetric flow rate, fluid properties, spray angle, droplet diameter, and subcooling was proposed by Mudawar and Estes (Mudawar and Estes, 1996). For low superheat, Hsieh et al. (Hsieh et al., 2004a) presented correlations for heat flux removed as a function of dimensionless parameters such as droplet Webber number and liquid Jacob number. Although this information would be useful for the formulation of new lubricants, it is difficult, if not impossible, to use correlations on boiling, droplet or water sprays developed for other processes. For example, boiling in droplets deposited on a hot surface differs from that observed in a pool boiling, since heat transfer relies on the contact area between the droplets and surface (Cui et al., 2003). The correlations obtained in the spray impingement studies are not applicable to the lubricant application process since there are significant differences between these processes. These differences include:

• Different superheat: in the die casting process, the superheat varies from 150 to 400 ◦C, while for power electronics and steel quenching is approximately less than 150 and larger than 1100 ◦C, respectively;

• different surface materials;

• different flow rates;

• transient versus uniform: most of boiling studies are for uniform state processes while the die lubrication is very transient, lasting from 0.2 to several seconds.

In the steady-state boiling three distinct regions exist: forced convection and evaporation, nucleate boiling, and critical heat flux, while in the transient cooling, the film boiling and transition boiling play an important role (Hsieh et al., 2004b). Gonzalez and Black (Gonzalez and Black, 1997) found that the interaction between spray and buoyant jet issued from a heated surface would reduce the droplet velocity.

The first principle approach, which was used to investigate spray cooling for other industries, is useful to investigate the fundamental phenomena and assess the effect of numerous parameters, but it would be difficult to implement in a plant environment. Other techniques, such as visualization had been recently used for the study of spray cooling. For low superheats, an array of individually controlled microheaters mounted on a transparent silica substrate was employed (Horacek et al., 2005). The spatial distribution of the heat flux was obtained at constant surface temperature while visualization and measurements of the liquid–solid contact area and the three-phase contact line length were made using an internal reflectance technique (Horacek et al., 2005). For die lubrication, the interaction between powder lubricants and molten alloy was observed with high-speed video system (Kimura et al., 2002). The result of in situ observation revealed that an enhanced insulating ability was due to formation of thin gaseous film between molten alloy and die by vaporized wax.

In most studies on the lubricant application effects, heated plate systems that mimic the die casting dies were employed and temperature data were obtained using thermocouples that were embedded into the plates (Lee et al., 1989; Garrow, 2001). The heat transfer coefficients (or heat fluxes) were obtained using either simple data extrapolation or inverse heat transfer procedures. In some of these studies, the data were recorded at low frequencies, e.g., only two data points per second were taken in Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2000). Due to the thermocouple response time, the temperature data could be very different than the actual temperature. In order to avoid cumbersome analysis of the data, such as performing inverse heat transfer analysis or accounting for the thermocouple response time (Reichelt et al., 2002), a sensor was used by Sabau and Wu (Sabau and Wu, 2007) for the direct measurement of heat flux. In addition to the heat flux data, the sensor provided data on the surface temperature, enabling the computation of the heat transfer coefficient. The temperature distribution of the average heat flux for water spray, which was presented by Sabau and Wu (Sabau and Wu, 2007), was similar that for the wellknown pool-boiling curve, validating the use of these sensors for the direct measurement of heat fluxes under conditions specific to the die casting process.

In this study, a complementary effort to the first principle approach was undertaken to characterize the lubricant performance. The lubricant behavior was evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), heat flux sensors (HFS), and infrared imaging. The Diluco 135TM lubricant, which was supplied by Cross Chemical Company, Inc., was used in this study. This Diluco lubricant was formulated for magnesium castings. Based on the information provided by the manufacturer, this lubricant was formulated with refined oils, natural and synthetic polymers, natural and synthetic waxes, wetting agents and emulsifying agents in order to aid in the mold release process. A dilution ratio of 15:1 for the water:lubricant mixture was recommended by the manufacturer.

In the second section, thermogravimetric analysis differential thermal analysis (DTA) was used to determine lubricant decomposition characteristics since these properties of the lubricant are important for its performance and casting quality. For example, if the lubricant vaporizes fast and at low temperatures, the molten metal would make contact directly with the die material and lubricant would not fulfill its function. On the other hand, if the atmosphere in the die cavity would include significant amounts of volatile decomposition products, there is higher probability of gas entrapped into the molten metal, giving rise to defects that would decrease the casting quality. In the third section, the results for the heat flux and surface temperature, which were measured using a heat flux sensor, were presented. During the experiments, the distance between the spray nozzle and plate was held constant.

چکیده

1. مقدمه

2. تجزیه روان کار

3. آزمایش های اعمال روان کار

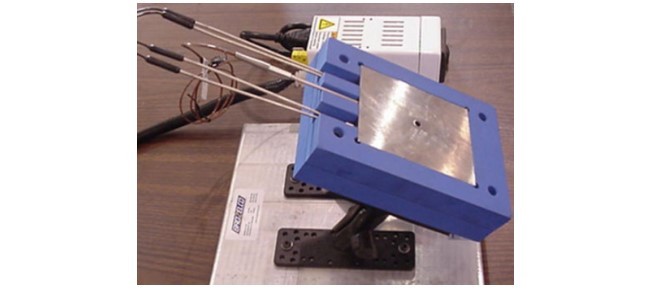

3.1 حسگر شار حرارتی

3.2 داده های شار حرارتی

4. تصویربرداری مادون قرمز

4.1 نتایج تصویربرداری مادون قرمز

5. نتیجه گیری

منابع

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Lubricant decomposition

3. Lubricant application experiments

3.1. Heat flux sensor

3.2. Heat flux data

4. Infrared visualization

4.1. Infrared imaging results

5. Conclusion

References