دانلود رایگان تحقیق انگلیسی هویت واقعی توماس ادیسون نابغه با ترجمه فارسی

هویت واقعی توماس ادیسون نابغه

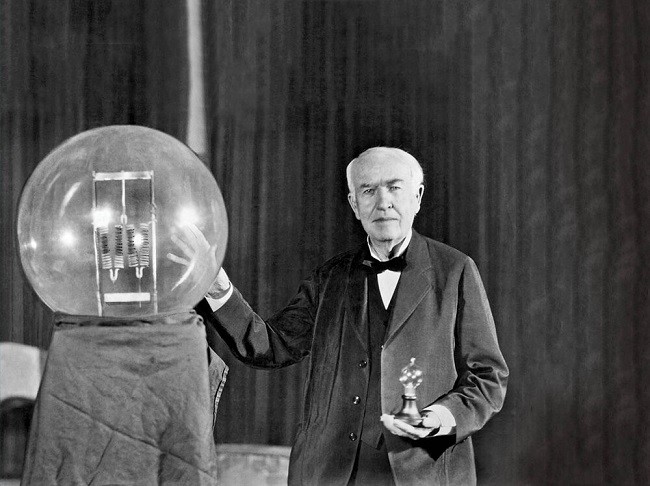

قبل از اینکه لامپ وجود داشته باشد ایده هایی وجود داشت. اما از بین تمام ایده هایی که تاکنون به اختراع تبدیل شده اند، فقط لامپ به نماد ایده ها تبدیل شده است. نوآوری های قبلی از تجربه «دیدن نور» به معنای واقعی کلمه جانبه گرایی میکردند، اما هیچکس در مورد لحظه های نور مشعل صحبت نکرد یا ایده شمع ها را در حباب های کارتونی ترسیم کردند. چیزی که لامپ را به تصویری قوی برای ایده ها تبدیل کرد، نه تنها اختراع، بلکه مخترع آن بود.

توماس ادیسون تا زمانی که لامپ های رشته ای طولانی مدت را کامل ساخت، به خوبی شناخته شده بود، اما آنقدر از او در کنار یکی از لامپ ها عکس گرفته میشد که عموم مردم این لامپ ها را با خود اختراع مرتبط میکردند. این مورد نوعی ویژگی گذرا بود: ادیسون در طول زندگی خود 1093 اختراع مختلف را ثبت کرد. او یک روز در سال 1888، صد و دوازده ایده را نوشت. به طور متوسط در طول دوران بزرگسالی خود، تقریباً هر یازده روز یک بار چیزی را به ثبت رساند. البته لامپ و گرامافون، کینتوسکوپ، دستگاه تایپ، باتری قلیایی و کنتور برق هم بین این موارد بود. بعلاوه: یک دستگاه شیره گیر، یک عروسک سخنگو، بزرگترین سنگ شکن جهان، قلم برقی، نگهدارنده میوه و خانه ضد گردباد از اختراعات او محسوب میشد.

همه این اختراعات کارساز یا منبع درآمدری برای وی نبودند. ادیسون هرگز با قلم خود برای نابینایان به جایی نرسید. مبلمان بتنی او اگرچه بادوام بود اما از بین رفت و نوآوری های ناموفق او در معدن، شانس را برای او از بین برد. اما او بیش از صد شرکت تأسیس کرد و هزاران دستیار، مهندس، ماشین کار و محقق را به کار گرفت. در زمان مرگ او، طبق یک تخمین، حدود پانزده میلیارد دلار از اقتصاد ملی تنها از اختراعات او به دست آمد. او یک نام آشنا بود، نه تنها به این دلیل که نام او در هر خانواده ای سر زبان ها بود بلکه نام وی بر روی وسایل، دستگاه ها و محصولاتی که مدرن بودن را برای بسیاری از خانواده ها تعریف می کرد، حک شده بود.

مخالفان ادیسون اصرار دارند که بزرگترین اختراع او شهرت خودش بود که با هزینه همکاران و رقبا به دست آمد. مدافعان او اظهار می کنند که شهرت او با هوش و ذکاوت وی متناسب بود. با این حال، حتی برخی از تحسینکنندگان او، شکل خاص اختراع او را که هرگز برای خلق چیزی از هیچ نبود، اشتباه متوجه شده اند. هویت واقعی نبوغ او در «ادیسون» (محصول انتشارات راندوم هاوس)، زندگینامه جدیدی از ادموند موریس، نویسنده ای که به طرز معروفی در مورد اینکه یک زندگی نامه نویس چقدر باید مبتکر باشد، مشخص میشود. موریس که به خاطر کتاب های سه گانه اش درباره تئودور روزولت تحسین شد، به خاطر کتاب عجیبش درباره رونالد ریگان مورد سرزنش قرار گرفت. ادیسون ممکن است فهمیده باشد که چگونه جهان را روشن کند، اما موریس ما را به این فکر وادار می کند که چگونه میتوان به بهترین شکل یک زندگی را روشن کرد.

البته ادیسون واقعاً لامپ را اختراع نکرد. مردم از سال 1761 سیم های رشته ای میساختند و بسیاری از مخترعان دیگر تا سال 1878 زمانی که ادیسون توجه خود را به مشکل روشنایی معطوف کرد، نسخه های مختلفی از چراغ های رشتهای را نشان داده و حتی به ثبت رساندند. هدیه ادیسون، در اینجا و جاهای دیگر، اختراعی نبود که آن را کامل سازی مینامید بلکه یافتن راه هایی برای بهتر یا ارزانتر کردن اشیا یا هر دو بود. ادیسون به دنبال مشکلاتی نبود که نیاز به راه حل داشته باشند. او به دنبال راه حل هایی بود که نیاز به اصلاح داشتند.

ادیسون که در سال 1847 در اوهایو به دنیا آمد و در میشیگان بزرگ شد، از کودکی آزمایش میکرد، زمانی که یک آزمایشگاه شیمی در زیرزمین خانه اش ساخت. تلاش اولیه تنها باعث خشم مادرش شد که نگران انفجارها بود، بنابراین، در سیزده سالگی، کارآفرین جوان شروع به فروش تنقلات به مسافرانی کرد که در راه آهن محلی از پورت هارون به دیترویت سفر می کردند. او همچنین نسخه هایی از مطبوعات آزاد دیترویت را برای فروختن در راه خانه بر میداشت. در سال 1862، پس از نبرد شیلو، او هزار نسخه خرید، زیرا میدانست که همه آنها را میفروشد و هر چه از راه آهن دورتر میرفت، قیمت را بیشتر و بیشتر میکرد. در حالی که هنوز در سنین نوجوانی خود بود، یک لتر پرس قابل حمل خرید و شروع به چاپ روزنامه خود در قطار در حال حرکت کرد و دو طرف یک برگه را با نوشته های گوناگون محلی پر کرد. تیراژ آن به چهارصد در هفته افزایش یافت و ادیسون باربر را در اختیار گرفت. او یک آزمایشگاه شیمی کوچک نیز در آنجا ساخت.

یک روز، ادیسون پسر خردسال رئیس ایستگاه را دید که روی ریل ها بازی می کرد و قبل از اینکه قطاری که از روبرو می آمد او را له کرد، پسر را به مکان امنی کشید. به عنوان پاداش، پدر به ادیسون کد مورس را آموزش داد و به او نحوه کار با دستگاه های تلگراف را نیز نشان داد. این موضوع در آن تابستان مفید بود، زمانی که آزمایشگاه ادیسون باعث آتش سوزی شد، متصدی او را از قطار اخراج کرد. ادیسون که مجبور به ترک روزنامه شد، چند سال بعد را به عنوان یک تلگراف برای وسترن یونیون و سایر شرکت ها گذراند و در هر کجا که کار مرتبطی پیدا می کرد آن را انتخاب کرد مثل شرکت های ایندیانا، اوهایو، تنسی، کنتاکی. او زمان داشت تا در کنار کارهای خود نیز آزمایش کند و اولین اختراع خود را در سال 1869 به ثبت رساند: یک ضبط کننده رأی الکتریکی که نیاز به فراخوانی را با شمارش فوری آرا از بین می برد. آنقدر خوب کار کرد که هیچ نهاد قانونگذاری آن را نخواست، زیرا در میان آرا مثبت و منفی زمانی را برای اعمال نفوذ باقی نگذاشت.

این شکست ادیسون را از هرگونه علاقه به اختراع منصرف نکرد: از آن زمان به بعد، او ذائقه کارعملی و سودآوری را در خود پرورش داد. اگرچه قانونگذاران نمیخواستند آرای آنها سریع تر شمارش شود، اما بقیه میخواستند همه چیز در سریعترین زمان ممکن پیش برود. برای مثال، شرکتهای مالی، اطلاعات سهام خود را سریع میخواستند، و شرکتهای ارتباطی میخواستند خدمات تلگرام خود را سرعت بخشند. اولین محصولات سودآور ادیسون یک دستگاه گیرنده تلگراف و یک تلگراف تمام جهتی بود که قادر به ارسال چهار پیام در آن واحد بود. او که صاحب آن اختراعات بود، برای تحقیقات تلگراف خود حمایت مالی پیدا کرد و از پول وسترن یونیون برای خرید یک ساختمان متروکه در نیوجرسی استفاده کرد تا به عنوان کارگاه استفاده کند.

در سال 1875، پس از رشد بیشتر در آن مکان، سی هکتار را در نزدیکی نیوآرک خرید و شروع به تبدیل ملک به چیزی کرد که دوست داشت آن را کارخانه اختراع خود بنامد. این آزمایشگاه یک آزمایشگاه دو طبقه با آزمایشات شیمی در طبقه بالا و یک ماشین فروش در پایین بود. کارگاه ها حداقل به قدمت هفائستوس هستند، اما کارگاه ادیسون اولین مرکز تحقیق و توسعه در جهان بود - مدلی که بعداً توسط دولت ها، دانشگاه ها و شرکت های رقیب پذیرفته شد. همانطور که شناخته شد، منلو پارک، مسلماً مهمترین اختراع ادیسون بود، زیرا بسیاری از موارد دیگر را با اجازه دادن به تقسیم مسائل به اجزای شیمیایی، الکتریکی و فیزیکی مجزا، که تیم هایی از کارگران میتوانستند از طریق تئوری و سپس آزمایش البته قبل از حرکت مستقیم به تولید حل کنند، تسهیل کرد.

منلو پارک همچنین شامل یک خانه سه طبقه برای خانواده ادیسون بود. در سال 1871، زمانی که بیست و چهار ساله بود، با دختری شانزده ساله به نام مری استیلول ازدواج کرد که در هنگام طوفان باران به دفتر او پناه برده بود. آنها سه فرزند داشتند که ادیسون دو تای آنها را دات و دش نامید. احتمالاً به لطف آنها، اولین ضبط صوتی ساخته شد که در نوامبر 1877، پاپا ادیسون را در حال خواندن "مری یک بره کوچک داشت" را نشان می دهد.

منبع:

http://www.newyorker.com

The Real Nature of Thomas Edison’s Genius

There were ideas long before there were light bulbs. But, of all the ideas that have ever turned into inventions, only the light bulb became a symbol of ideas. Earlier innovations had literalized the experience of “seeing the light,” but no one went around talking about torchlight moments or sketching candles into cartoon thought bubbles. What made the light bulb such an irresistible image for ideas was not just the invention but its inventor.

Thomas Edison was already well known by the time he perfected the long-burning incandescent light bulb, but he was photographed next to one of them so often that the public came to associate the bulbs with invention itself. That made sense, by a kind of transitive property of ingenuity: during his lifetime, Edison patented a record-setting one thousand and ninety-three different inventions. On a single day in 1888, he wrote down a hundred and twelve ideas; averaged across his adult life, he patented something roughly every eleven days. There was the light bulb and the phonograph, of course, but also the kinetoscope, the dictating machine, the alkaline battery, and the electric meter. Plus: a sap extractor, a talking doll, the world’s largest rock crusher, an electric pen, a fruit preserver, and a tornado-proof house.

Not all these inventions worked or made money. Edison never got anywhere with his ink for the blind, whatever that was meant to be; his concrete furniture, though durable, was doomed; and his failed innovations in mining lost him several fortunes. But he founded more than a hundred companies and employed thousands of assistants, engineers, machinists, and researchers. At the time of his death, according to one estimate, about fifteen billion dollars of the national economy derived from his inventions alone. His was a household name, not least because his name was in every household—plastered on the appliances, devices, and products that defined modernity for so many families.

Edison’s detractors insist that his greatest invention was his own fame, cultivated at the expense of collaborators and competitors alike. His defenders counter that his celebrity was commensurate with his brilliance. Even some of his admirers, though, have misunderstood his particular form of inventiveness, which was never about creating something out of nothing. The real nature of his genius is clarified in “Edison” (Random House), a new biography by Edmund Morris, a writer who famously struggled with just how inventive a biographer should be. Lauded for his trilogy of books about Theodore Roosevelt, Morris was scolded for his peculiar book about Ronald Reagan. Edison may have figured out how to illuminate the world, but Morris makes us wonder how best to illuminate a life.

Edison did not actually invent the light bulb, of course. People had been making wires incandesce since 1761, and plenty of other inventors had demonstrated and even patented various versions of incandescent lights by 1878, when Edison turned his attention to the problem of illumination. Edison’s gift, here and elsewhere, was not so much inventing as what he called perfecting—finding ways to make things better or cheaper or both. Edison did not look for problems in need of solutions; he looked for solutions in need of modification.

Born in 1847 in Ohio and raised in Michigan, Edison had been experimenting since childhood, when he built a chemistry laboratory in his family’s basement. That early endeavor only ever earned him the ire of his mother, who fretted about explosions, so, at thirteen, the young entrepreneur started selling snacks to passengers travelling on the local railroad line from Port Huron to Detroit. He also picked up copies of the Detroit Free Press to hawk on the way home. In 1862, after the Battle of Shiloh, he bought a thousand copies, knowing he would sell them all, and marked up the price more and more the farther he got down the line. While still in his teens, he bought a portable letterpress and started printing his own newspaper aboard the moving train, filling two sides of a broadsheet with local sundries. Its circulation rose to four hundred a week, and Edison took over much of the baggage car. He built a small chemistry laboratory there, too.

One day, Edison saw a stationmaster’s young son playing on the tracks and pulled the boy to safety before an oncoming train crushed him; as a reward, the father taught Edison Morse code and showed him how to operate the telegraph machines. This came in handy that summer, when Edison’s lab caused a fire and the conductor kicked him off the train. Forced out of newspapering, Edison spent the next few years as a telegrapher for Western Union and other companies, taking jobs wherever he could find them—Indiana, Ohio, Tennessee, Kentucky. He had time to experiment on the side, and he patented his first invention in 1869: an electric vote recorder that eliminated the need for roll call by instantly tallying votes. It worked so well that no legislative body wanted it, because it left no time for lobbying amid the yeas and nays.

That failure cured Edison of any interest in invention for invention’s sake: from then on, he cultivated a taste for the practical and the profitable. Although legislators did not want their votes counted faster, everyone else wanted everything else to move as quickly as possible. Financial companies, for instance, wanted their stock information immediately, and communication companies wanted to speed up their telegram service. Edison’s first lucrative products were a stock-ticker device and a quadruplex telegraph, capable of sending four messages at once. Armed with those inventions, he found financial support for his telegraphy research, and used money from Western Union to buy an abandoned building in New Jersey to serve as a workshop.

In 1875, having outgrown that site, he bought thirty acres not far from Newark and began converting the property into what he liked to call his Invention Factory. It was organized around a two-story laboratory, with chemistry experiments on the top floor and a machine shop below. Workshops are at least as old as Hephaestus, but Edison’s was the world’s first research-and-development facility—a model that would later be adopted by governments, universities, and rival corporations. Menlo Park, as it came to be known, was arguably Edison’s most significant invention, since it facilitated so many others, by allowing for the division of problems into discrete chemical, electrical, and physical components, which teams of workers could solve through theory and then experimentation before moving directly into production.

Menlo Park also included a three-story house for Edison’s family. In 1871, when he was twenty-four, he married a sixteen-year-old girl named Mary Stilwell, who had taken refuge in his office during a rainstorm. They had three children, two of whom Edison nicknamed Dot and Dash. It is likely thanks to them that the first audio recording ever made, in November of 1877, features Papa Edison reciting “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

Source:

http://www.newyorker.com

| لامپ رشته ای | light bulb |

| نماد | symbol |

| رسم کردن | sketching |

| ماشین تایپ | dictating machine |

| ضد طوفان | tornado-proof |

| نابودی | doom |

| دستیار | assistant |

| تخمین زدن | estimate |

| مدرن بودن | modernity |

| مخالف | detractor |

| حک شده | plastered |

| به دست آمدن | Cultivate |

| همکار | Collaborator |

| نشان دادن | demonstrate |

| روشنایی | illumination |

| ترس | fret |

| متصدی | conductor |

| مجزا کردن | division |

| اجزا | components |

| خواندن | recite |