دانلود رایگان مقاله طراحی زنجیره تامین با در نظر گرفتن اقتصادهای مقیاس

چکیده

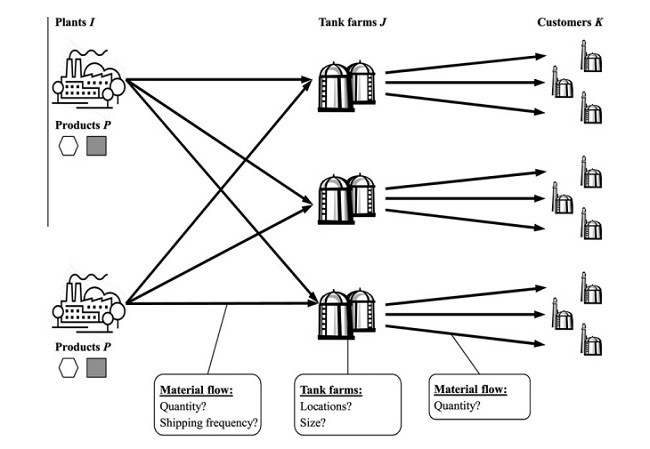

در این مقاله, ما یک مدل طراحی زنجیره تامین چند محصولی 3-مرتبه ای را با اقتصادهای مقیاس در حمل و نقل و انبارداری در نظر می گیریم که به صراحت فراوانی حمل و نقل در آن در نظر گرفته می شود. مدل ما به طور همزمان, موقعیت ها و اندازه محوطه مخازن, جریان های موارد و فراوانی حمل و نقل را در درون این شبکه بهینه سازی می کند. ما تمام هزینه های مرتبط را در نظر می گیریم: هزینه محصول, هزینه حمل و نقل, هزینه کرایه مخزن, هزینه توان عملیاتی مخزن و هزینه موجودی. این مسئله بر اساس یک نمونه واقعی از یک شرکت شیمیایی است. نشان خواهیم داد که در نظر گرفته اقتصادهای مقیاس و فراوانی حمل و نقل در مرحله طراحی, حیاتی است و عدم موفقیت در انجام آن منجر به هزینه های قابل توجه بالاتر از هزینه های بهینه و مطلوب می شود. انواع گسترده ای از مسائل را با راه حل شاخه و کران و با ابتکارات راه حل کارآمد مبتنی بر تکنیک های خطی سازی تکراری که توسعه داده ایم, حل می نماییم. ما نشان می دهیم که این ابتکارات نسبت به تکنیک استاندارد شاخه و کران, برای مسائل بزرگی چون یکی از شرکت های شیمیایی که به تحقیق ما مرتبط هستند عالی تر هستند.

1. مقدمه

افزایش جهانی شدن و گستردگی آن به افزایش روزافزون حجم حمل و نقل ها منجر شده است. یکی از صنایعی که تغییرات زیادی را به خود دیده است, صنعت شیمیایی است. در طی دهه اخیر, بسیاری از شرکت ها در این صنعت, سایت های تولید جهانی را تاسیس نموده اند و از این سایت ها برای برآورده سازی تقاضاهای جهانی استفاده نموده اند. به طور مثال Bayer (2007), برای سرمایه گذاری 1.8 میلیارد دلار آمریکا در سایت تولید Toluylen–Diisocyanat (TDI) در شانگهای در سال 2009 برنامه ریزی نمود و برای این کار, ظرفیت تولید این سایت را دو برابر و به 300000 تن در هر سال رساند. سرمایه گذاری های مشابهی توسط بسیاری از شرکت های دیگر صورت گرفته است. BASF (2007) ظرفیت های کارخانه های خود را در Nanjing, Ludwigshafen, Antwerp, و Pasir Gudang از 2002 تا 2006 گسترش دادند و یک کارخانه جدید را در Pudong در سال 2006 افتتاح نمودند. SABIC (2006,2007), the Saudi Basic Industries Corporation, که یک تولیدکننده پیشرو در مواد شیمیایی, کودها, پلاستیک ها و فلزات است, شبکه جهانی خود را با تسلط بر تجارت پتروشیمیDutch group DSM (2002), عملیات های پتروشیمی Huntsman’s UK, و عملیا های GE Plastics برای ایالات متحده (2006) گسترش داد. در سال 2006, SABIC تقریباً 500 شناور را برای حمل و نقل 8.6 میلیون تن مواد شیمیایی و گاز به بیش از 90 بندر در بیشتر از 35 کشور در سراسر دنیا استفاده نمود.

برای تطبیق تقاضای جهانی با عرضه جهانی, شرکت های شیمیایی از زنجیره های عرضه جهانی استفاده نمودند. معمولاً, محصولات در کارخانه های معدودی تولید می شوند و به محوطه های مخازن منطقه ای منتقل می شوند و در آنجا ذخیره می شوند. بنابراین تقاضای مشتری با استفاده از این محوطه های مخازن منطقه ای برآورده می شود. در بیشتر وضعیت ها, مخازن تحت مالکیت یک اپراتور محوطه قرار دارند که مخازن را به شرکت های شیمایی کرایه می دهد. هنگام طراحی یک زنجیره تامین (عرضه), شرکت ها باید چند تصمیم بگیرند: تصمیم گیری در مورد ترکیب محصول و کمیت هیا تولید در سایت های تولید, در موقعیت های محوطه مخازن و ظرفیت های مخازن و در مورد فراوانی تحویل ها بین کارخانه ها. این تصمیمات طراحی زنجیره تامین, تصمیمات متوسط تا بلند مدت هستند و معمولاً به صورت سالانه یا دوسالانه گرفته می شوند.

ساختار هزینه زنجیره های تامین مواد شیمیایی, چندین صرفه جویی مقیاسی (اقتصادهای مقیاس) مهم را نشان می دهد که باید در زمان طراحی زنجیره تامین در نظر گرفت. مهم ترین آنها, صرفه جویی های مقیاسی در کمیت های حمل و نقل و در ظرفیت های مخازن است. نرخ کرایه کشتی بین اروپا و آمریکای جنوبی, به عنوان نمونه, از حدود به کاهش یافته است, در حالیکه حجم حمل و نقل از 1000 به 10000 مترمکعب افزایش یافته است. هزینه های کرایه مخازن, صرفه جویی های مقیاسی مشابه را نشان می دهد. هزینه کرایه یک مخزن معمولی 500 مترمکعبی, به عنوان نمونه, (54 دلار آمریکا/مترمکعب/در سال) است در حالیکه هزینه کرایه یک مخزن معمولی 500 مترمکعبی, به عنوان نمونه, است.

تحقیقات قبلی به برخی از موضوعات پرداخته اند که در زمان طراحی زنجیره های تامین مانند موردی که ما در نظر می گیریم, به یکدیگر مرتبط هستند. هرچند, از نظر ما, رویکردی وجود ندارد که تمام این مشخصات اصلی را به طور همزمان در نظر گرفته باشد: طراحی ترکیبات محصول, مسیرهای حمل و نقل, فراوانی حمل و نقل, موقعیت های انبارش مواد, اندازه های انبارش و ذخیره, در نظر گرفتن موارد غیرخطی در حمل و نقل و هزینه های انبارش. از آنجا که تصمیمات عمدتاً بر یکدیگر تاثیر می گذارند, آنها باید به طور همزمان برای کسب یک طراحی زنجیره تامین کارآمد گرفته شوند و نمی توانند به طور مستقل از یکدیگر گرفته شوند.

مدل حاصل؛ یک مسئله جریان شبکه خطی تکه ای غیرمحدب است که به عنوان سخت-NP نامیده می شود (مثلاً Kim and Pardalos, 2000b). ما تکنیک Balakrishnan and Graves (1989) را برای بیان مدل خود به عنوان برنامه ترکیبی- عدد صحیح به کار می بریم. برای حل موثر مسائلی در اندازه واقعی, روش های راه حل ابتکاری جدید را توسعه دادیم. کار ما بر اساس یک پروژه برای یک شرکت شیمیایی است که زنجیره تامین دریایی آن را دوباره طراحی نمود و ما تحلیل های عددی خود را بر اساس داده های این شرکت پایه نهادیم. با این حال, کاربرد این مدل و رویکردهای راه حل به این محیط محدود نمی شوند. آنها برای طراحی زنجیره های تامین در صنایع دیگر که مشخصات مشابه با صنعت شیمیایی دارند, مانند صنایع زغال سنگ, فلز, سنگ, نفت و گاز قابل استفاده هستند.

بقیه این مقاله به شرح زیر سازماندهی شده است. در بخش 2, نوشته های مرتبط را بررسی می نماییم. در بخش 3, مسئله طراحی زنجیره تامین را از نظر ریاضی مدلسازی می نماییم. تاکید خاص ما بر مدلسازی موارد غیرخطی در هزینه ها به طور دقیق و گنجاندن تعداد تحویل به عنوان متغیرهای تصمیم گیری می باشد. در بخش 4, چندین ابتکار را برای حل مسائل طراحی زنجیره تامین دنیای واقعی توسعه می دهیم. همچنین نشان می دهیم که چگونه راه حل های بهینه را می توان برای مسائل در اندازه کوچک تا متوسط محاسبه نمود و چگونه می توان یک حد پایین را برای عملکرد خط مشی بهینه محاسبه نمود. در بخش 5, ما تعدادی از مسائل را حل می کنیم و عملکرد ابتکارات را مقایسه می نماییم. نتایج ما نشان می دهد که این ابتکارات, راه حل هایی را تولید می کند که نزدیک به بهینگی هستند. همچنین ما مزایای مدل جامع خود را در برابر مدل های ساده شده نشان می دهیم. در بخش 6, نتیجه گیری می نماییم.

2. مرور نوشته ها

در ارتباط با تحقیقات ما, نوشته هایی در مورد مدل های طراحی زنجیره تامین با هزینه ذخیره غیرخطی و هزینه حمل و نقل خطی, مدل هایی با هزینه ذخیره خطی و هزینه حمل و نقل غیرخطی و مدل هایی با ذخیره غیرخطی و هزینه حمل و نقل غیرخطی وجود دارند. ما نوشته های مرتبط را در این بخش مرور می نماییم.

مدل ها با هزینه ذخیره غیرخطی و هزینه حمل و نقل خطی برای سایت های ظرفیت دار و بدون ظرفیت توسعه یافته اند. Feldman et al (1966), یک مدل بدون ظرفیت را معرفی نمودند که با ابتکار جمع و کم کردن حل نمودند. اصلاحات این روش برای مسائل بدون ظرفیت توسط Spielberg (1969a,b), Drysdale and Sandiford (1969), Khumawala and Kelly (1974), and Whitaker (1985) توسعه یافته است. Baxter (1984) از یک نسخه پیوسته این مسئله استفاده نمود که در آن, انبارها را می توان در هر جایی قرار داد و به مجموعه ای از موقعیت های بالقوه از پیش تعریف شده محدود نمی شوند. او این مسئله را با یک روش تخصیص-موقعیت و تشویق حل نمود. رویکردهای راه حل بهینه توسط Efroymson and Ray (1966) توسعه یافته است و آنها از روش شاخه و کران برای حل این مسئله استفاده نمود و Broek et al. (2006) نیز آن را با اتکا بر الگوریتم آزادسازی لاگرانژ توسعه داد.

Abstract

In this paper we consider a 3-echelon, multi-product supply chain design model with economies of scale in transport and warehousing that explicitly takes transport frequencies into consideration. Our model simultaneously optimizes locations and sizes of tank farms, material flows, and transport frequencies within the network. We consider all relevant costs: product cost, transport cost, tank rental cost, tank throughput cost, and inventory cost. The problem is based on a real-life example from a chemical company. We show that considering economies of scale and transport frequencies in the design stage is crucial and failing to do so can lead to substantially higher costs than optimal. We solve a wide variety of problems with branch-and-bound and with the efficient solution heuristics based on iterative linearization techniques we develop. We show that the heuristics are superior to the standard branch-and-bound technique for large problems like the one of the chemical company that motivated our research.

1. Introduction

Increasing globalization and vertical disintegration have resulted in a large increase of transportation volumes. One of the industries that has experienced radical changes is the chemical industry. During the last decade, many companies in this industry have established global production sites and use these sites to meet global demands. Bayer (2007), for instance, planned to invest 1.8 billion USD into a Toluylen–Diisocyanat (TDI) production site in Shanghai by 2009, doubling the production capacity of this site to 300,000 tons per year. Similar investments have been made by many other companies. BASF (2007) expanded the capacities of its plants in Nanjing, Ludwigshafen, Antwerp, and Pasir Gudang from 2002 to 2006 and opened a new plant in Pudong in 2006. SABIC (2006, 2007), the Saudi Basic Industries Corporation, a leading manufacturer of chemicals, fertilizers, plastics, and metals, expanded its global network by taking over the petrochemicals business of the Dutch group DSM (2002), Huntsman’s UK petrochemical operations (2006), and GE Plastics’ US-based operations (2006). In 2006, SABIC used nearly 500 vessels to ship over 8.6 million metric tons of chemicals and gases to more than 90 ports in over 35 countries around the world.

To match global demand with global supply, chemical companies use global supply chains. Typically, products are produced at a few plants and are shipped to regional tank farms, where they are stored. Customer demand is then met utilizing these regional tank farms. In most situations, the tanks are owned by a tank farm operator that rents the tanks to chemical companies. When designing a supply chain, companies must make a number of decisions: they must decide on the product mix and production quantities at the production sites, on the locations of the tank farms and tank capacities, and on the frequency of deliveries between plants. These supply chain design decisions are medium- to long-term decisions and are typically made annually or bi-annually

The cost structure of chemical supply chains exhibits several important economies of scale that have to be considered when designing the supply chain. The most important ones are economies of scale in transportation quantities and economies of scale in tank capacities. The freight rate between Europe and South America, for instance, decreases from about 400 USD/m3 to 200 USD/m3 when the transportation volume increases from 1000 m3 to 10,000 m3 . The costs of tank rentals exhibit similar economies of scale. The rental cost of a typical 500 m3 tank, for instance, is 54 USD/m3 /year, whereas the cost of a 2000 m3 tank is only 24 USD/m3 /year.

Previous research has addressed some of the issues that are relevant when designing supply chains like the one we consider. However, to our best knowledge, there does not exist an approach that considers all of the main characteristics simultaneously: design of product mixes, transportation routes, transportation frequencies, storage locations, and storage sizes, taking into account non-linearities in transportation and storage costs. Since the decisions greatly impact one another, they must be made simultaneously to obtain an efficient supply chain design and cannot be made independently. The main contribution of the paper is that it provides an approach for modeling and solving such complex supply chain design problems with economies of scale and transport frequencies and that it provides numerical results from a realworld application.

The resulting model is a non-convex piecewise linear network flow problem, which is known to be NP-hard (e.g. Kim and Pardalos, 2000b). We apply the technique of Balakrishnan and Graves (1989) to state our model as a mixed-integer program. To solve problems of realistic size efficiently, we developed new heuristic solution methods. Our work is based on a project for a chemical company that redesigned its sea freight supply chain and we base our numerical analyses on data of this company. However, the application of the model and the solution approaches are not limited to this setting. They can also be used for designing supply chains in other industries that exhibit similar characteristics as the chemical industry, such as the coal, metal, stone, oil, and gas industries.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the relevant literature. In Section 3, we model the supply chain design problem mathematically. We place particular emphasis on modeling non-linearities in costs accurately and on incorporating delivery frequencies as decision variables. In Section 4, we develop several heuristics for solving real-world supply chain design problems. We also show how the optimal solutions can be computed for small to medium-sized problems and how a lower bound on the performance of the optimal policy can be computed. In Section 5, we solve a number of problems and compare the performances of the heuristics. Our results indicate that the heuristics generate solutions that are close to optimality. We also show the advantages of our comprehensive model versus simplified models. In Section 6, we draw conclusions.

2. Literature review

Related to our research are the literature on supply chain design models with non-linear storage cost and linear transportation cost, models with linear storage cost and non-linear transportation cost, and models with non-linear storage and non-linear transportation cost. We review the corresponding literature in this section.

Models with non-linear storage cost and linear transportation cost have been developed for uncapacitated and capacitated sites. Feldman et al. (1966) introduced an uncapacitated model that they solved with add and drop heuristics. Refinements of the add and drop heuristic for uncapacitated problems have been developed by Spielberg (1969a,b), Drysdale and Sandiford (1969), Khumawala and Kelly (1974), and Whitaker (1985). Baxter (1984) used a continuous version of the problem, where warehouses can be located anywhere and are not restricted to a set of predefined potential locations. He solved the problem with an adaptive locationallocation and perturbation method. Optimal solution approaches have been developed by Efroymson and Ray (1966), who used branch-and-bound to solve the problem, and by Broek et al. (2006), who relied on Lagrangian relaxation.

چکیده

1. مقدمه

2. مرور نوشته ها

3. فرمولاسیون مدل

3.1 هزینه حمل و نقل بین سایت های تولید و محوطه های مخزن

3.2 هزینه تولید

3.3 هزینه ذخیره

3.4 هزینه حمل و نقل بین محوطه های مخزن و مشتریان

3.5 خطی سازی هزینه حمل و نقل و ذخیره

3.6 مدل ریاضی

4. رویکرد راه حل

4.1 راه حل مستقیم با کد استاندارد شاخه و کران

4.2 خطی سازی توسط آزادسازی انتگرالیته

4.3 خطی سازی توسط فرمولاسیون دوباره مدل

5. نتایج محاسباتی

5.1. مقایسه رویکردهای راه حل ابتکاری و دقیق

5.2 اثر فرمولاسیون مسئله بر عملکرد زنجیره تامین

6. نتیجه گیری

abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

3. Model formulation

3.1. Transportation cost between production sites and tank farms

3.2. Production cost

3.3. Storage cost

3.4. Transportation cost between tank farms and customers

3.5. Linearization of transportation and storage cost

3.6. Mathematical model

4. Solution approach

4.1. Direct solution with a standard branch-and-bound code

4.2. Linearization by integrality relaxation

4.3. Linearization by model reformulation

5. Computational results

5.1. Comparison of exact and heuristic solution approaches

5.2. Effect of problem formulation on supply chain performance

6. Conclusion

References