دانلود رایگان مقاله تعارض در روابط، همخوانی نام خانواده با شرکت و ثروت اجتماعی

چکیده

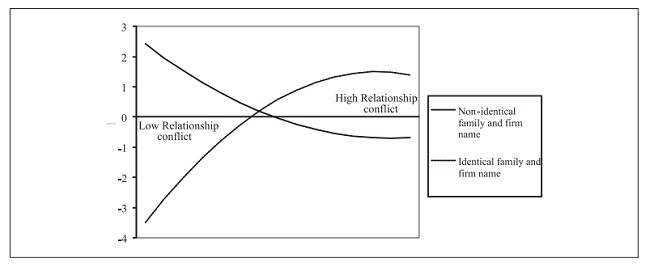

در این مقاله به بررسی این مسئله می پردازیم که چگونه تعارض روابط و همخوانی نام شرکت و خانواده بر ارزشیابی های شخصی مالک-مدیر شرکت خانوادگی تاثیر می گذارد. از دیدگاه ثروت اجتماعی احساسی و نظریه سازمان رفتاری، رابطه یو شکل را بین تعارض داخل شرکت خانواده و ارزش گذاری شخصی شرکت می یابیم. در حالی که تاثیر مستقیم بین همخوانی اسمی و ارزشیابی شخصی شرکت نیافتیم، نشان می دهیم که همخوانی اسمی تاثیر متقابل با تعارض رابطه داشته و بر ارزشیابی ها تاثیر می گذارد. مفاهیم و اثرگذاری های یافته های ما بررسی می شوند.

مقدمه

«طرفین به طور دوستانه تمامی اختلاف های خود را خارج از دادگاه حل و فصل می کنند و در انتظار رشد بی وقفه کسب و کار هستند. این بدان معنا نیست که خصومت از بین رفته است. واژه ها و تاکتیک های تند در طی سال ها همانند زخم های ماندگار اند که درمان آنها زمان زیادی می برد (گرانت، 2017)».

ثروت اجتماعی احساسی نوعی ابزار غیر مالی است که بر بخشش های مطلوب به مالکیت شرکت های خانوادگی تاثیر می گذارد. محققین از محیط شرکت خانوادگی برای بررسی ثروت اجتماعی احساسی استفاده می کنند چون نکات غیرمالی در این زمینه رایج اند. لذا ابزار غیرمالی یا ثروت اجتماعی احساسی به عنوان مولفه پایه ای دارندگان ارزش کل بوده که بر مالکیت در شرکت خانوادگی تاثیر می گذارد. با این وجود یافته های اخیر نشان میدهند که ثروت اجتماعی احساسی بر ارزشیابی شرکت از جانب صاحبان شرکت تاثیر می گذارد. ارزشگذاری شخصی شرکت خانوادگی را حداقل بهای قابل قبول می دانیم که مایل به شرکت بپردازیم.محققین نشان می دهند که تمایل صاحبان به حفظ و ارتقا ثروت اجتماعی احساسی رفتار شرکت خانواده و تصمیم گیری را پیش می برد. به هر حال ادبیات توصیف نکرده اند که مالکین چگونه به تجارب منفی مربوط به شرکت های خانوادگی رسیدگی می کنند که ازاین به بعد آنها را هزینه های اجتماعی احساسی می نامیم.

در این مقاله با مدل سازمان رفتاری و ثروت اجتماعی احساسی و نظرات ترکیبی، به بررسی نحوه بررسی هزینه اجتماعی احساسی توسط مالکین مبتنی بر تعارض رابطه و ارزشیابی شخصی شرکت می پردازیم. این فرض شهودی را به چالش می کشیم که هزینه های اجتماعی احساسی منجر به ارزشیابی های پایین تر می شوند. به طور ویژه رابطه یو شکل بین تعارض رابطه در شرکت های خانوادگی مطرح می کنیم.چنین فرضیه سازی می کنیم که همخوانی نام خانواده تاثیر متقابل در تعارض رابطه و ارزشیابی شرکت دارد.

این مقاله چند اثر بر ادبیات و نوشته ها دارد. نخست اینکه ادبیات ثروت اجتماعی احساسی را گسترش می دهیم و به بررسی هزینه های اجتماعی اقتصادی مربوط به کارکردهای منفی از جمله تعارض در رابطه می پردازیم. طبق فرضیه ها نشان می دهیم که مالکین هزینه های اجتماعی احساسی را به حالت غیرشهودی و غیرخطی هنگام ارزیابی شرکت در نظر میگیرند. این یافته ها مفاهیمی برای نحوه نگرش محققان به عکس العمل صاحبان شرکت به دامنه وسیع تر هزینه های اجتماعی اقتصادی دارند. دوم اینکه مقاله حاضر به درک بهتر ارزشیابی فردی شرکت های خانوادگی می افزاید. سوم اینکه مقاله ما به نگرش های نظریه نگرشی می افزاید و نشان می دهد که تاثیر بخشش چه رابطه ای با تعارض رابطه و همخوانی نام خانواده دارد. بدین ترتیب، یافته های ما مفاهیمی برای داره کردن شرکت خانوادگی، انتقال مالکیت شرکت خانوادگی خصوصی دارند. در آخر اینکه ادبیات مربوط به تعارض روابط را گسترش می دهیم. لذا پیچیدگی های تعارض شرکت خانوادگی که قبلا در ادبیات و نوشته ها مطرح نشده اند به بحث رایج درباره ناهمگونی شرکت خانوادگی می افزاید.

ثروت اجتماعی احساسی و ارزشیابی شرکت خانوادگی

ثروت اجتماعی احساسی «جنبه غیرمالی شرکت می باشد که نیازهای تاثیرگذار خانواده را برطرف می کند.» که این مقوله همچنین بخشش اثرگذار یا بخشش اجتماعی احساسی نام دارد. ثروت اجتماعی احساسی به شرح نحوه پیگیری اهداف غیرمالی و رفتار شرکت خانوادگی کمک می کند. ارزش گذاری شخصی شرکت از جانب مالکین آن برجستگی خاصی در محیط شرکت خانوادگی دارد. ارزیابی شرکت های خانوادگی در اکثر حالات شخصی است. این ارزشیابی ها پیچیده اند که شامل احتمال نیز هستند و اغلب به لحاظ مسائل مطلوبیت اجتماعی یک سو نگر هستند. در این شرایط فرایندهای شناختی افراد دخیل هستند که بر ارزشیابی ها تاثیر می گذارند. برای درک نحوه عملکرد ثروت اجتماعی احساسی به عنوان نقطه مرجع جهت تاثیر بر ارزشگذاری شخصی مالکیت شرکت خانوادگی، یک سو نگری هایی در فرایند تصمیم گیری وارد می کند.نخست با نظریه نگرش، پیش بینی خط مبنا برای حالت معمولی فراهم می کنیم. تاثیر بخشش به تفاوت بین بهایی می پردازد که در آن فرد مایل است به خرید و فروش شی بپردازد. نظریه نگرش همچنین تمایل دارندگان به سرمایه گذاری قبلی نشان میدهد. در نتیجه، تصمیم گیرندگان با نسبت دادن ارزش به سرمایه گذاری های قبلی زمان، پول و اثرگذاری تمایل کمی به تقسیم دارایی از خود نشان می دهند. همچنین مالکین این هزینه ها را بخشی از ارزش دارایی می دانند. تحقیقات قبلی نشان می دهند این مسئله درباره دارایی ها به ویژه بخشش های اجتماعی احساسی در رابطه با مالکیت شرکت خانوادگی درست است. لذا متناسب با نظریه دورنما، انتطار داریم مالکین مولفه غیرمالی هنگام تصمیم گیری قیمت فروش قابل قبول شرکت خانوادگی را در نظر بگیرند. به علاه نظریه دورنما، نشان می دهد که ارزش فردی مربوط به مولفه غیرمالی ارزشگذاری شرکت به احتمال زیاد به سمت تاثیر مثبت مربوط به ثروت اجتماعی احساسی مربوط می گردد. لذا نظریه دورنما را در این حالت کلی به کار می بریم که نمی تواند به طور کامل نحوه نگرش مالکین به تاثیر منفی در ارزشگذاری های فردی نشان دهد. برای نمونه می دانیم که برخی جوانب مالکیت شرکت خانوادگی از جمله تعارض در رابطه توام با تاثیر منفی اند.با این وجود نمی دانیم که آیا مالکین تاثیر منفی در ارزشگذاری ثروت اجتماعی احساسی را در ارزشیابی شرکت در نظر می گیرند. به علاوه نمی دانیم که آیا نقطه مرجع مالکین برای ارزشگذاری شخصی هنوز شامل مولفه غیرمالی در حالت تاثیر منفی می باشد. برای بررسی این پیچیدگی ها، نظریه پردای خود را فراتر از نظریه دورنما گسترش میدهیم و از منطق ترکیبی و بی.ای.ام استفاده می کنیم. بی.ای.ام در ادبیات شرکت های خانوادگی بر مبنای تاثیر بخشش می باشد که در نظریه دورنما تاکید گردید. بی.ام.ای نقطه مرجع عمده مالکین به تصمیم گیری می باشد.در واقع تحقیقات قبلی نشان می دهند که انگیزه حفظ ثروت اجتماعی احساسی بر تصمیمات شرکت های خانوادگی تاثیر می گذارد. به کارگیری بی.ای.ام فرض ضمنی تاثیر متقابل بین ثروت اجتماعی احساسی و ثروت مالی است. ادبیات با گسترش بی.ام.ای به معرفی شرط بندی های ترکیبی در نظریه پردازی می پردازند تا پتانسیل پیامد برد و باخت را در چارچوب تصمیم گیرنده در نظر بگیرند. در واقع برومیلی خاطر نشان می کند که تصمیمات کمی وجود درد که شامل فرصت فقط باخت یا فقط برد می باشند. این مباحث نظری می توانند رفتار شرکت خانواده پیچیده را شرح دهند. برای مثال در حالی که ادبیات از قبل نشان می دهند که اجتناب از باخت ثروت اجتماعی احساسی منجر به عدم سرمایه گذاری در تحقیق و توسعه می گردد، با توجه به دیدگاه های نظری بالا، می توانیم بردهای را به خاطر تحولات در نقاط مرجع درک کنیم. تحقیقات اخیر کاتلر با همکاران نشان دهنده ماهیت پویا نقاط مرجع صاحب شرکت خانواده می باشد که منجر به تغییراتی در ارزشیابی ثروت اجتماعی احساسی می گردد. چون تاثیر متقابل بین ثروت مالی و ثروت اجتماعی احساسی مستقیم نیست و در بین شرکت های خانواده ناهمسان است، این تاثیرات متقابل مفاهیمیبرای ارزشگذاری شرکت دارند و میزان تعارض رابطه متغییر فرایند شرکت خانوادگی عمده بوده که بر ارزشگذاری های فردی تاثیر میگذارد. به علاوه همخوانی نام شرکت خانواده نحوه ارزیابی مالکین شرکت و تاثیر تعارض رابطه در ارزشیابی های کلی را تغییر می دهد. در زیر به طور مفصل به این روابط می پردازیم.

تعارض رابطه و ارزشیابی شرکت های خانوادگی

تعارض رابطه به عنوان «آگاهی از ناسازگاری بین فردی تعریف می شود که شامل مولفه های اثرگذار از جمله تنش احساسات و برخورد می باشد.» امازون (1996) به تفکیک ناپذیری رابطه تعارض و تاثیر منفی پرداخته و واژه تعارض اثرگذار را به کار می گیرد. پریم و پرایش از برچسب «تعارض اجتماعی احساسی» استفاده می کنند تا به توصیف تعارض منفی بپردازند. تعارض رابطه با اختلافات، مشاجره، مانور سیاسی، رقابت، خصومت و پرخاشگری توصیف می گردد و توام با احساسات منفی از جمله خشم، ناامیدی، تنفر، خصومت و آزردگی است. طبق نظر داچ تعارضات رابطه اراده خوب، درک متقابل، تکمیل فعالیت های سازمانی و عملکرد را کاهش می دهند یا مانع می شوند. جن (1995) همچنین نشان می دهد که تعارض در رابطه منجر به رضایتمندی کاهش یافته و عدم توجه به دیگر اعضا گروه می گردد. تا کنون شواهدی نشان دهنده تاثیرات مثبت تعارض رابطه بر عملکرد یا رضایتمندی نیست.

تعارض در رابطه در شرکت های خانوادگی رایج است و پیامدهای ناگوار دارد. ماهیت تعارض در شرکت های خانوادگی پیچیده و متمایز است که به خاطر رابطه بین نظام خانواده و شرکت است. برای نمونه بی صلاحیتی عضو خانواده، استحقاق، فرصت طلبی سرمایه گذاری ثروت اجتماعی احساسی را از بین می برد و منجر به تعارض در رابطه می گردد. همچنین تعارض در رابطه ممکن است در شرکت های خانوادگی تشدید گردد که به خاطر تعارضات بین اعضا خانوادگی در محل کار محیط خانواده است. این تعارضات نهادینه شده و به دشوار حل و فصل می شوند چون خانواده ها گروه های اجتماعی با خاطره های ماندگار هستند. تعارض در رابطه منجر به هزینه اجتماعی احساسی می گردد که نوعی بی اعتمادی و ناسازگاری در بین اعضا خانواده پدید می آورد. در زیر رابطه بین تعارض در رابطه و ارزشیابی فردی مالک شرکت را بررسی می کنیم.

وقتی تعارض در رابطه نباشد، یعنی روابط سازگار باشند، می توان انتظار تاثیر مثبت، افزایش تعهد به شرکت و افزایش ثروت اجتماعی احساسی را داشت. با توجه به روابط خانوادگی مثبت درون شرکت، انتظار داریم مالکین ارزشیابی های فردی را بر اساس تمایل به حفظ ثروت اجتماعی احساسی چارچوب بندی کنند.

Abstract

We investigate how family relationship conflict and family and firm name congruence influence subjective firm valuations by family firm owner-managers. Drawing on the socioemotional wealth perspective, behavioral agency theory and mixed gamble reasonings, we hypothesize and find a U-shaped association between relationship conflict inside the family firm and subjective firm valuation. While we do not find a direct effect between name congruence and subjective firm valuation, we show that name congruence interacts with relationship conflict to affect valuations in a complex fashion. Implications and contributions of our findings are discussed.

Introduction

“The parties have amicably resolved all of their disputes out of court and look forward to the continued growth of the business. That doesn’t mean the animosity is gone. The harsh words and tactics over the years left wounds that will take a long time to heal (Grant, 2017).”

Socioemotional wealth (SEW) is the nonfinancial utility or affective endowments attached to ownership of the family firm (Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007). Scholars use a family business setting to investigate owners’ socioemotional utility because nonfinancial considerations are prevalent in this context (Gedajlovic, Carney, Chrisman, & Kellermanns, 2012). As such, nonfinancial utility, or socioemotional wealth is recognized as an integral component of the total value owners attribute to ownership in the family firm (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, 2008; Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008; Zellweger & Dehlen, 2012). Yet recent findings show that SEW can also detract from firm valuation and trade-offs between financial wealth and SEW are made (Kotlar, Signori, De Massis, & Vismara, 2018). Accordingly, the subjective valuation of the family firm by its owners accounts for both the financial and nonfinancial utility of ownership (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, 2008; Kammerlander, 2016). Specifically, we define subjective valuation of the family firm as the minimum acceptable price at which owners would be willing to sell the firm to a buyer from outside the family (Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, & Chua, 2012).Scholars show that owners’ desire to preserve and enhance SEW drives family firm behavior and decision making (e.g., Berrone, Cruz, Gómez-Mejía, & Larraza Kintana, 2010; Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Gómez-Mejía, Patel, & Zellweger, 2018; Zellweger, Kellermanns,Chrisman, et al., 2012); however, the literature does not describe how owners handle negative experiences related to the family firm, hereafter referred to as socioemotional costs. Socioemotional costs arise from negative features related to ownership, such as relationship conflict and the associated negative emotions (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, 2008), as well as sacrifice and pressure (Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008).

In this study, we draw on SEW, behavioral agency model (BAM; Wiseman & Gómez-Mejía, 1998), and mixed gambles (e.g., Gómez-Mejía et al., 2014), which are all three grounded in prospect theory, to investigate how owners account for the socioemotional cost of relationship conflict in their subjective valuation of the family firm. We challenge the intuitive assumption that socioemotional costs would automatically lead to lower valuations. We propose that socioemotional costs such as relationship conflict among family members are viewed differently by family members and can thus increase or decrease subjective valuations of the family firm. Specifically, we hypothesize a U-shaped relationship between relationship conflict in family firms (e.g., Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007) and subjective firm valuations; whereby low levels and high levels of relationship conflict promote greater levels of subjective valuations. We further hypothesize that family name congruence, evident by the presence of identical firm and family owner names, interacts with relationship conflict to influence subjective valuations. Indeed, family name congruence between the owning family and firm is shown to affect the presence of SEW (GómezMejía, Cruz, Berrone, & De Castro, 2011).

Our study makes multiple contributions to the literature. First, we extend the SEW literature by examining socioemotional costs associated with negatively valenced functions such as relationship conflict. To this point, the literature has only been mostly concerned with positively valenced sources of SEW. Rather than a simple depletion of SEW, we hypothesize and demonstrate that owners account for socioemotional costs in a counterintuitive, nonlinear fashion when assigning subjective value to the family firm. These findings have implications for how scholars view family firm owners’ potential responses to a broader range of negatively valenced socioemotional costs. It also provides new insights on the research of mixed gambles in SEW and the role of vulnerability (e.g., Gómez-Mejía et al., 2014; Martin, Gomez-Mejia, & Wiseman, 2013). Second, we contribute to a better understanding of the subjective valuation of family firms by their owners (e.g. Foss, Klein, Kor, & Mahoney, 2008; Kotlar et al., 2018; Leitterstorf & Rau, 2014; Thomsen & Pedersen, 2000; Zellweger, Richards, Sieger, & Patel, 2016; Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, et al., 2012). Third, our article adds to the insights of the wider prospect theory by showing how an endowment effect can be driven by relationship conflict and family name congruence (Carmon & Ariely, 2000; DeSteno, Petty, Wegener, & Rucker, 2000; Lerner, Small, & Loewenstein, 2004; Loewenstein & Lerner, 2003). As such, our findings have implications for family firm governance (Lubatkin, Schulze, Ling, & Dino, 2005) and the transfer of private family firm ownership (e.g., Capron & Shen, 2007). Finally, we extend the literature on relationship conflict (e.g., Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Jehn, 1995) by not only tying relationship conflict to firm valuation but also by showing that the curvilinear relationship varies based on family name congruence. This suggests complexities of family firm conflict not previously acknowledged in the literature and contributes to the ongoing debate on family firm heterogeneity (e.g., Chua, Chrisman, Steier, & Rau, 2012; Stanley, Kellermanns, & Zellweger, 2017; Westhead & Howorth, 2007).

Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Valuation

SEW is “the non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s affective needs” (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007, p. 106) and is also referred to as affective endowment or socioemotional endowment (Berrone, Cruz, & GómezMejía, 2012; Gómez-Mejía, Makri, & Larraza-Kintana, 2010). SEW helps explain how the pursuit of nonfinancial goals drives family firm behavior (cf. Chua, Chrisman, & De Massis, 2015; Martin & Gómez-Mejía, 2016; Miller & Breton-Miller, 2014; Schulze & Kellermanns, 2015).The subjective valuation of the firm by its owners is particularly salient in the family firm setting owing to the affect-dense setting of the family system (Anderson & Reeb, 2003; Sharma & Manikutty, 2005) and the prominence of SEW as a primary reference point (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007) since ownership is typically maintained within the family with transgenerational sustainability intentions in mind and as the firm is typically not for sale outside the family (Zellweger et al., 2016).Valuing privately held family firms is subjective in most cases as no liquid market for shares exists (Fernando, Schneible, & Suh, 2014). These valuations are complex, involve considerable uncertainty, and are often biased by social desirability concerns (e.g., family legacy considerations). In these circumstances, individuals’ cognitive processes are likely to be infused by affect (Forgas, 1995), whereby affect primes what is selectively recalled and interpreted and, ultimately, biases valuations.To further our understanding of how SEW acts as a reference point to influence the subjective valuation of family firm ownership (Zellweger & Dehlen, 2012), which is likely to impose biases in the decision process, we use multiple approaches. First, we draw on prospect theory to establish a baseline prediction for the typical case. The endowment effect, a central tenet of prospect theory, explains the difference between the price at which an individual is willing to purchase and sell an object. Prospect theory postulates that it takes a more advantageous offer to make an individual sell an endowed asset in comparison to the price at which the individual would be willing to buy the same asset, owing to loss aversion and a bias toward the status quo (Tversky & Kahneman, 1991). Prospect theory also recognizes the propensity for owners to capitalize prior investments such that they are less willing to relinquish an asset for its current market value even if the decision puts that value at risk (Arkes & Blumer, 1985). As a consequence of attributing value to prior investments of time, money, and affect, decision makers display a decreasing willingness to part with the asset (Moon, 2001). Likewise, owners can consider these costs to be part of the value of an asset, thereby heightening its minimum acceptable sale price (Thaler, 1980). Prior research suggests this is particularly true of affect-infused assets, specifically the socioemotional endowments related to family firm ownership (Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008; Zellweger & Dehlen, 2012). Thus, consistent with prospect theory, we expect owners to include the nonfinancial component of giving up the SEW associated with ownership when deciding the minimum acceptable sales price of the family firm. Moreover, prospect theory suggests the subjective value attached to the nonfinancial component of firm valuation will most likely be biased upward given the positive affect associated with SEW, and the reluctance to relinquish it.Yet we propose the application of prospect theory to this general case cannot fully explain how owners account for negative affect in subjective valuations. For example, we know that some aspects of family firm ownership, such as relationship conflict, are infused with negative affect (Zellweger, Kellermanns, Chrisman, et al., 2012). Yet we do not know if owners account for negative affect in their evaluation of SEW by simply reducing their SEW assessment and with it firm valuation. Furthermore, we do not know if the owner’s reference point for subjective valuation will still incorporate a nonfinancial component (SEW) in the case of negative affect or shift solely to the financial wealth component of the valuation. To address these complexities, we extend our theorizing beyond prospect theory and draw on both BAM and mixed gambles reasoning in SEW.BAM (Wiseman & Gómez-Mejía, 1998) in the family firm literature builds on the endowment effect emphasized in prospect theory, suggesting that the value owners place on preserving SEW is associated with ownership in the family firm. BAM proposes the owner’s primary reference point for decision making is framed by aversion to loss of the current SEW endowment (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Indeed, prior research shows that motivation to preserve SEW influences family firm decisions (e.g., Berrone et al., 2010; Chrisman & Patel, 2012; Patel & Chrisman, 2014). The applications of BAM often hold the implicit assumption of a trade-off between SEW and financial wealth (Martin & Gómez-Mejía, 2016).

Relationship Conflict and Valuation in Family Firms

Relationship conflict is defined as “an awareness of interpersonal incompatibilities [that] includes affective components such as feeling tension and friction” (Jehn & Mannix, 2001, p. 238). Amason (1996) echoes the inseparability of relationship conflict and negative affect and adopts the term affective conflict, and Priem and Price (1991) use the label “social-emotional conflict” to describe negative conflict. Relationship conflict is characterized by disagreements, argumentation, political maneuvering, competition, hostility, and aggression (Barki & Hartwick, 2004). Relationship conflict is embedded with a wide array of negative emotions such as anger, frustration, hatred, animosity, and annoyance (Barki & Hartwick, 2004; De Dreu & Weingart, 2003). According to Deutsch (1969), relationship conflicts decrease goodwill, mutual understanding, and camaraderie, which hinder the completion of organizational tasks and work performance. Jehn (1995) also shows that relationship conflict leads to reduced satisfaction and a lack of regard for other group members. To date, no evidence shows positive effects of relationship conflict on either performance or satisfaction (McKee, Madden, Kellermanns, & Eddleston, 2014).

Relationship conflict is prevalent in family firms (e.g., Beehr, Drexler, & Faulkner, 1997; Danes, Zuiker,Kean, & Arbuthnot, 1999; Dyer, 1986; Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004) and can often have disastrous consequences (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007). The dynamics of conflict in family businesses are complex and distinctive because of the unique interdependence between family and business systems (Memili, Chang, Kellermanns, & Welch, 2015; Sorenson, 1999). For example, family member incompetence, entitlement, or opportunism may undermine the SEW investment by other family members and lead to relationship conflict (Eddleston & Kidwell, 2012; Kidwell, Kellermanns, & Eddleston, 2012). Also, relationship conflict may become particularly intense in family firms because conflicts among family members are sustained in repetitive interactions in both work and family settings (e.g., Kaslow, 1993). These relationship conflicts become institutionalized and difficult to resolve because families are social groups with long histories and enduring memories, and the personal costs of exiting either the family or firm are high (Schulze, Lubatkin, & Dino, 2003). Thus, rather than providing an endowment, relationship conflict could lead to socioemotional cost, which can manifest itself as hostile rejection, abject dependence, mental distrust, manipulation, and maladaptation among family members (Eddleston & Kellermanns, 2007; Kellermanns & Eddleston, 2004). Below, we will argue the connection between relationship conflict and the family firm owner’s subjective valuation of the firm in more detail.

In the absence of relationship conflict, that is, in harmonious relationships, positive affect can be expected (Isen & Baron, 1991), heightening commitment to the firm and increasing SEW. Given the positive family relationships within the firm, we expect owners to frame subjective valuations based on the desire to preserve socioemotional endowments associated with ownership in the firm (Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008). Prospect theory/BAM suggests that owners will not only place a high value on the current SEW endowment but also be strongly averse to losing it (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). Owners will therefore include a premium for relinquishing SEW in their subjective valuation of the firm.

چکیده

مقدمه

ثروت اجتماعی احساسی و ارزشیابی شرکت خانوادگی

تعارض رابطه و ارزشیابی شرکت های خانوادگی

همخوانی اسمی شرکت و خانواده و ارزشیابی در شرکت های خانوادگی

تاثیر متقابل همخوانی نام با تعارض رابطه بر ارزشیابی فردی

روش

متغییر وابسته

متغییرات مستقل

متغییرات کنترل

متغییرات کنترل مالی.

متغییرات کنترل غیرمالی.

آزمون های یک سونگری

نتایج

آزمون های پایایی

بحث و نتیجه گیری

محدودیت ها و تحقیقات آتی

Abstract

Introduction

Socioemotional Wealth and Family Firm Valuation

Relationship Conflict and Valuation in Family Firms

Family and Firm Name Congruence and Valuation in Family Firms

The Interaction of Name Congruence With Relationship Conflict on Subjective Valuation

Method

Dependent Variable

Independent Variables

Control Variables

Tests for Bias

Results

Robustness Tests

Discussion and Conclusion

Limitations and Future Research

Acknowledgements

Notes

References