دانلود رایگان مقاله تاثیر بر سهامدار و تنوع درآمدهای مالی در ازای مسئولیت اجتماعی

به عقیده من، تحقیقات درباره جنبه کسب و کار مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت باید ماهیت مسیر روابط شرکت-سهامدار را مد نظر قرار دهند و من ساختار ظرفیت تاثیر سهامدار را برای پر کردن این شکاف مطرح می کنم. این ساختار شرح می دهد که چرا تاثیرات مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت بر عملکرد مالی شرکت در بین شرکت ها و بسته به زمان فرق می کند. من یک سری پیشنهادات برای کمک به تحقیقات آتی در زمینه شرایط تولید سود مالی متغییر جهت سرمایه گذاری در مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت مطرح می کنم.

جان هاید، بازنشسته پلیس ویل کالیف می گوید که به دشوار می توان باور نمود که فیلیپ موریس «مرد خوبی است بر این اساس که برای قربانیان سیل زده آب اهدا می کند، یا اینکه به گرسنگان کمک می کند» (السپ، 2002).

تردید زیادی وجود دارد مبنی بر اینکه چه زمانی یک شرکت همچون مک دونالد شروع می کند درباره سالاد صحبت کند، چون مردم می دانند که مک دونالدز به طور ویژه به سلامت آمریکایی اهمیت نمی دهد.

به نظرم، این مسئله به این بستگی دارد که آیا آن بخشی از تصویر کلی است. همانند کراگر، این اقدام یک باره نیست، آنها قوطی های برای بی خانمان ها یا چیزی در جشن شکرگزاری و کریمس می آورند. این نوعی تجارت برای آنها محسوب می گردد.

آیا شرکت های دولتی باید به عنوان نماینده تحولات اجتماعی پیش رونده محسوب شوند؟ برای نمونه، آیا لوی استراز گروه حامی برای خاتمه بخشی به نژاد پرستی تشکیل داد؟ آیا شرکت فورد به یافتن دارو ایدز کمک نمود؟ این شرکت ها تا چه حد به آرمان های اجتماعی کمک نموده اند؟ چون در پاسخ به این سوالات، مسائل اخلاقی وجود دارد، افراد منطقی اختلاف نظر دارند. برخی معتقدند که چون شرکت ها منابع را از جوامع استخراج می کنند، آنها تعهد اخلاقی در قبال خدمات رسانی به جامعه دارند، در حالی که سایرین باور دارند شرکت ها در قبال کمک رسانی به جامعه ناکارآمد اند.

با توجه به این بحث اخلاقی، محققان زیادی به بررسی «نمونه کسب و کار» مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت پرداخته اند. حجم فزاینده ای از ادبیات به بررسی این مسئله پرداخته اند که آیا مزایای مالی شرکت هزینه ها را جبران نموده و بر رفاه اجتماعی تاثیر می گذارد. بدین ترتیب، مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت را می توان به عنوان سرمایه گذاری عاقلانه توجیه کرد، اگر این طور نباشد، مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت را می توان به عنوان مسئله واسطه مورد اعتراض قرار داد. نتیجه اینکه پس از سی سال تحقیق، نمی توانیم به طور واضح به این نتیجه برسیم که آیا سرمایه گذاری یک دلاری در فعالیت های اجتماعی بیش از یک دلار سود را برای سهام دار به بار می آورد.

جنبه ابهام کسب و کار به انواع نقائص موچود در تحقیقات محققان برمی گردد که این مسئله را از زوایای دید نظری مختلف بررسی نموده اندهمانطور که قدرت مطالعات مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت افزایش یافته است تا این نقائص را بررسی کنند، رابطه بین مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت و عملکرد مالی هنوز تیره مانده است. ماگولیس والش اخیرا کمبود مطالعات تجربی درباره رسیدگی به این مسئله را خاطر نشان نموده اند. در نتیجه این مسئله تنش پیرامون پاسخگویی شرکت به مشکلات اجتماعی را بدتر می کند. لذا مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت به عنوان معمای اخلاقی باقی می ماند.

بی نظمی بی وقفه درباره نمونه کسب و کار نباید به عنوان مسئله شگفت آور تلقی گردد.ویژگی منحصر به فرد و پویا شرکت و محیط آنها مانع از پایداری سود مالی به ازای مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت در گذر زمان و در میان شرکت ها می گردد لذا نباید انتظار داشته باشیم که مزیت مالی دائمی را –ضرورتا نرخ جهانی سود- در یک شرکت عمومی به ازای واحد سرمایه گذاری اجتماعی تجربه خواهیم کرد. رستوران های مک دونالدز و ساب وی را در نظر بگیرید. هر چند صنعت یکسان دارند و با شرایط رقابت مشابه رو به رو می شوند، هر کام برای کنترل چاقی 1 میلیون دلار کمک می کنند، اما تجربه سود مالی مشابه در آنها، احتمالی است. در واقع سود آنها فرق می کند و یک مورد به سود مثبت دست یافته و دیگری زیان را تجربه می کند. حتی درون یک شرکت، درجات مشابه سرمایه گذاری مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت در گذر دوره های زمانی مختلف احتمالا منجر به سودهای مالی مختلف می گردد. لذا تلاش ها برای مشروعیت نمودن یا محکم نمودن یک نمونه کسب و کار «به طور نظری غیرقابل دفاع» است.

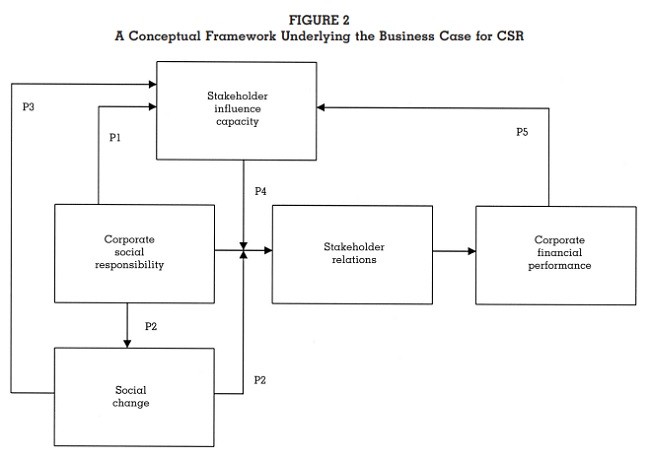

محققان اغلب شرایط زیادی را نادیده می گیرند که باعث نوسان در سود مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت می گردد. در نتیجه، نمونه کسب و کار علی رغم تحقیقات گسترده نه ایجاد می گردد و نه بی اعتبار می شود. هدف من در این مقاله کمک به جهت دهی مجدد تحقیقات مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت به دور از نزاع بلند مدت بر سر یافته های تجربی تکرار پذیر سود مالی مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت می باشد تا عومل پایه ای سود مالی مثبت ناشی از مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت مشخص گردد. همچنین چارچوب مفهومی ارائه می دهد که شرح می دهد چگونه شرکت ها سود مالی از کارکردهای مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت حاصل می کنند. شرکت ها بر مبنای استدلال نظریه سهامدار می توانند مزیت مالی کسب کنند به طوری که به سهامداران خود توجه کنند. در ادامه بخث می کنم که چگونه این مزایای مالی به خاطر ظرفیت تاثیر سهامدار در میان شرکت ها، و میزان استفاده از مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت جهت بهبود روابط متغییر است. سپس به مرور کلی نمونه کسب و کار جهت مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت می پردازم. سپس مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت را از چند مفهوم پیچیده دیگر متمایز می کنم. پس از آن، ساختار ظرفیت تاثیر سهامدار را معرفی کرده و آن را درون چارچوب مفهومی قرار داده و مرزهای این چارچوب را از طریق یک سری پیشنهادات شرح می دهم. این مقاله با بحث گسترده مفاهیم ظرفیت تاثیر سهامدار جهت آینده فعالیت ها و تحقیقات مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت به نتیجه گیری می رسد.

نمونه کسب و کار مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت

مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت اغلب به عنوان فعالیت احتیاط آمیز شرکت توصیف می گردد که هدف آن رفاه اجتماعی است. برای مثال تارگت بیان نمود که هر هفته بیش 2 میلیون دلار به خدمات اجتماعی، آموزشی و هنر در جوامعی اختصاص می دهد که در آن فروشگاه هایش مشغول به فعالیت اند. بسیاری از فعالتی های شرکت مبتنی بر رفاه جامعه، به لحاظ قانونی اجباری اند که می توان فرصت استخدام عادلانه و مرخصی پزشکی را نام برد. اما چرا در مواجه با رقابت شدید، شرکت های سودگرا به طور داوطلبانه منابع محدود و مازاد به رفاه اجتماعی به عنوان «فعالیت تقریبا جهانی» اختصاص می دهند؟ به طور یقین بهتر می توان از این منابع در جهت بهبود کارایی شرکت یا سود سهامدار بهره برد.

منتقدین مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت بر این عقیده اند که هزینه کردن منابع محدود درباره مسائل اجتماعی ضرورتا موقعیت رقابت آمیز شرکت را با افزایش هزینه های بی مورد، کاهش می دهد. به علاوه حتی اگر شرکتی دارای منابع کم اما بدون فرصت سرمایه گذاری مساعد باشد، و حتی اگر هزینه های مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت به حدکافی نباشد که به زیان رقابتی برای شرکت تبدیل گردد، شرکت هنوز می تواند از مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت خودداری کند. اختصاص منابع شرکتی به رفاه اجتماعی معادل توزیع غیرداوطلبانه ثروت از سهامداران تا سایر افراد در جامعه است. لذا هر چند مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت به طور کلی مد نظر است، اما برخی آن را نوعی هزینه بی مورد می دانند، مدیران مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت را برای سودآوری شخصی نه به سود سهامدار در پیش می گیرند (فریدمن، 1970). تعریف مک ویلیامز و سیگل از مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت، مثالی از این استدلال هزینه بی مورد می باشد: «ما مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت را به عنوان اقداماتی تعریف می کنیم که ظاهرا به سد جامعه بوده و فراتر ز منافع شرکت و چارچوب قانون است.» همچنین منقدین معتقدند که مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت چندان هم به سود شرکت عمل نمی کند.

I argue that research on the business case for corporate social responsibility must account for the path-dependent nature of firm-stakeholder relations, and I develop the construct of stakeholder influence capacity to fill this void. This construct helps explain why the effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance vary across firms and time. I develop a set of propositions to aid future research on the contingencies that produce variable financial returns to investment in corporate social responsibility.

John Hyde, a retiree in Placerville, Calif., says it’s hard to believe Philip Morris is “a good guy just because it donates water to flood victims, or helps the hungry” (Alsop, 2002: 1).

There is a lot of skepticism out there when a company like McDonald’s starts to talk about salads, because people know McDonald’s is not especially concerned about the health of America (Rich Polt, consultant, quoted in Dressel, 2003: 1).

I guess it depends if it’s [the firm’s participation in an act of corporate social responsibility] part of the total picture and [if] they really go out of their way. Like with Kroger, it isn’t a one-time shot, they’re always doing stuff for Egleston [Children’s Hospital], or they’ve got the big barrels out there for the people to bring cans for the homeless or something at Thanksgiving and Christmas. It just seems more a way of business for them, continuously, so in that case, that’s fine.... But if somebody’s doing it just for the publicity, then that would not make me think better of them (survey respondent quoted in Webb & Mohr, 1998: 235).

Should public corporations serve as agents of progressive social change? For example, should Levi Strauss fund a campaign to end racism? Should Ford contribute to finding a cure for AIDS? If so, how much should these corporations contribute to these social causes? Because there are ethical considerations inherent in answering these questions, reasonable people can and do disagree. Some argue that because corpora tions draw resources from society, they have a moral obligation to give back to society, whereas others counter that corporations are inefficient and inappropriate agents of social change, and any voluntary contributions to social causes are misappropriations of shareholders’ funds (Friedman, 1970).

Given the intractability of this ongoing ethical debate, many researchers have turned to examination of the “business case” for corporate social responsibility (CSR). A large and evergrowing body of literature has investigated whether the financial benefits to the corporation can meet or exceed the costs of its contributions to social welfare (for recent reviews, see Margolis & Walsh, 2003, and Orlitzky, Schmidt, & Rynes, 2003). If so, CSR can be justified as a wise investment; if not, CSR can be condemned as an agency problem. The result is that after more than thirty years of research, we cannot clearly conclude whether a one-dollar investment in social initiatives returns more or less than one dollar in benefit to the shareholder.

The lingering murkiness of the business case has been attributed to a variety of shortcomings present in the research of scholars approaching the topic from myriad (a)theoretical angles (Griffin & Mahon, 1997; Ullmann, 1985). Yet even as the rigor of CSR studies has increased to address these shortcomings, the link between CSR and financial performance has become only murkier. Margolis and Walsh recently described this body of research as “self-perpetuating: each successive study promises a definitive conclusion, while also revealing the inevitable inadequacies of empirically tackling the question”(2003: 278). As a result, it “reinforces, rather than relieves, the tension surrounding corporate responses to social misery” (Margolis & Walsh, 2003: 278). Thus, the seemingly tractable business case for CSR remains just as debatable as the associated ethical dilemma.

The continuing chaos surrounding the business case should not come as a surprise. The unique and dynamic characteristics of firms and their environments preclude stability in financial returns to CSR across firms and time, so we should not expect to empirically discern a consistent financial benefit— essentially, a universal rate of return—to a generic corporation for some given unit of social investment. Consider McDonald’s and Subway restaurants. Although they are both in the same industry and so face similar competitive conditions, were each to contribute $1 million to efforts to curb obesity, it is unlikely they would experience identical financial returns. In fact, their returns could differ radically, with one achieving a positive return and the other experiencing losses. Even within the same firm, identical levels of CSR investment over different time periods are likely to lead to different financial returns, such as before and after lawsuits, intense media scrutiny, or other external shocks (cf. Alsop, 2002; Hoffman, 1997). Thus, efforts to universally legitimize or condemn the business case are “theoretically untenable” (Rowley & Berman, 2000: 406).

Researchers have often overlooked the many contingencies that cause variability in returns to CSR, perhaps in their zeal to legitimize or discredit the business case (Rowley & Berman, 2000; Ullmann, 1985). As a result, the business case has been neither made nor discredited, despite extensive research (Margolis & Walsh, 2003). My goal for this paper is to help reorient CSR research away from the long-fought battle for replicable empirical findings of the financial returns to CSR in general and toward a quest for deeper understanding of the underlying drivers of whether and when particular firms may earn positive financial returns from CSR—in short, to make the business case firm specific, not universal. In furtherance of this goal, I present a conceptual framework that illustrates how firms generate financial returns from acts of CSR. Building on the stakeholder theory argument that firms can benefit financially from attending to the concerns of their stakeholders (Freeman, 1984), I discuss how these financial benefits vary as a result of stakeholder influence capacity, a construct that captures variation across and within firms in their ability to use CSR to profitably improve relationships.I next present an overview of the business case for CSR. I then distinguish CSR from several related and sometimes confounded concepts. Thereafter, I introduce the construct of stakeholder influence capacity, embed it within a conceptual framework, and elaborate the bounds of this framework through a set of propositions. The paper concludes with an extended discussion of the implications of stakeholder influence capacity for the future of CSR research and practice.

THE BUSINESS CASE FOR CSR

CSR is often described as any discretionary corporate activity intended to further social welfare. For example, Target reported that it donates more than $2 million each week to the arts, education, and social services in the communities in which its stores operate. The presence of discretion is key. Many corporate activities that further social welfare are mandated by law, such as equal employment opportunity and medical leave. But why, in the face of oftenfierce competition, do for-profit firms voluntarily allocate additional limited resources to social welfare as an “almost universal practice” (Dressel, 2003: 1)? Certainly, these resources could be put to better use in improving the efficiency of the firm, or could be returned to shareholders.

This is the core of the argument against CSR. Critics of CSR contend that expending limited resources on social issues necessarily decreases the competitive position of a firm by unnecessarily increasing its costs. Furthermore, even if a firm has slack resources but no favorable investment opportunities, and even if the costs of CSR are not ample enough to put the firm at a competitive disadvantage, the firm should still refrain from CSR. Devoting corporate resources to social welfare is tantamount to an involuntary redistribution of wealth, from shareholders, as rightful owners of the corporation, to others in society who have no rightful claim. Thus, CSR, although almost universally practiced, is considered by some to be an agency loss; managers pursue CSR for personal gain, not shareholder benefit (Friedman, 1970).

نمونه کسب و کار مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت

مرزهای مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت

تمایز مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت با عملکرد اجتماعی شرکت

تمایز مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت از دیگر تخصیص منابع شرکت

درون مرزهای مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت

خارج از مرزهای مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت

سرمایه گذاری های پیچیده و انگیزه های نهان.

شرح ناهمسانی در سود مالی مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت

جریانات مسئولیت اجتماعی شرکت سهام ظرفیت تاثیر سهامدار ایجاد می کنند

تاثیرات تحولات اجتماعی بر ظرفیت تاثیر سهامدار

ظرفیت تاثیر سهامدار به عنوان عامل واسطه

تناقض در عملکرد

بحث

نتیجه گیری

THE BUSINESS CASE FOR CSR

THE BOUNDARIES OF CSR

Distinguishing CSR from Corporate Social Performance

Distinguishing CSR from Other Corporate Resource Allocations

EXPLAINING HETEROGENEITY IN THE FINANCIAL RETURNS TO CSR

CSR Flows Build SIC Stocks

Effects of Social Change on SIC

The Paradox of Performance

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION