دانلود رایگان مقاله اثرات اولویت آیتم و تقویت رمز بر رفتار تسهیم نمایش داده شده توسط کودکان

چکیده

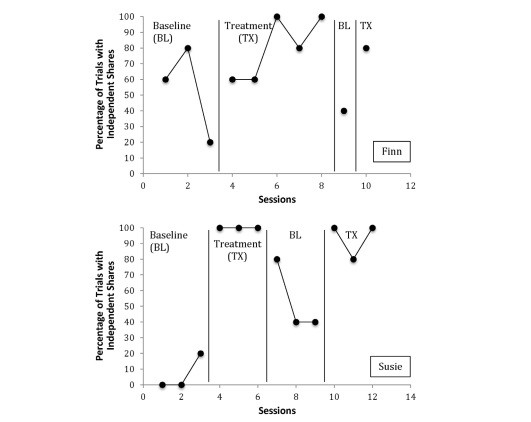

مطالعات کنونی، متغیرهای موثر بر تسهیم نمایش داده شده توسط کودکان مبتلا به اختلال طیف اوتیسم را مورد بررسی قرار دادند. مطالعه 1، اثرات دستکاری اولویت آیتم را بر روی سطح کمک مورد نیاز برای نمایش رفتار تسهیم در 4 کودک مبتلا به اوتیسم مورد بررسی قرار داد. اولویت آیتم به وضوح، 2 درصد شرکت کنندگان دارای تسهیم مستقل را تحت تاثیر قرار داد. اولویت، دارای اثر مشخصی برای شرکت کننده سوم نبود. با این حال، تسهیم یک آیتم اولویت-بالا به طور کلی به سطح بالاتری از اعلان (به عنوان مثال، برانگیختگی های سریع صوتی) برای تسهیم نیاز داشت. درصد تسهیم مستقل شرکت کننده چهارم توسط اولویت تحت تاثیر قرار نگرفت، و رفتار تسهیم مستقل او در سراسر اولویت آیتم ها مشابه بود. مطالعه 2، اثربخشی یک روش تقویت رمزی را به عنوان مداخله (درمان) طراحی شده برای افزایش تسهیم مستقل آیتم های اولویت-بالا برای دو شرکت کننده ای ارزیابی نمودند که آن ایتم ها را به طور مستقل در طول مطالعه 1 تسهیم نمودند. زمانی که روش رمزی به کار گرفته شد، تسهیم مستقل برای هر دو شرکت کننده افزایش یافت، و زمانی که این روش حذف شد، کاهش یافت.

کودکانی که اختلال طیف اوتیسم (ASD) در آنها تشخیص داده می شود، اختلافات کیفی را در ارتباط و تعامل اجتماعی تجربه می نمایند (انجمن روانپزشکی آمریکا، 2013). این نقص مداوم، تعاملات روزمره بین افراد مبتلا به ASD و همسالان آنها و مراقبان را به مشکل می کشاند. یک مهارت ضروری برای کودکان به منظور یادگیری توسعه روابط با همسالان و مشارکت مناسب در تعاملات اجتماعی، تسهیم است. تسهیم، و یا پاسخ به درخواست برای تسهیم، یک مهارت اجتماعی است که کودکان مبتلا به ASD برای تسلط بر آن تقلا می نمایند. ((Baron-Cohen، Leslie، و Frith، 1985؛ Eisenberg و Fabes، 1998؛ Marzullo-Kerth، Reeve، Reeve، و Townsend، 2011، Rheingold و Hay، 1980؛ Rutter، 1978؛ Volkmar، Carter، Sparrow، و Cicchetti، 1993؛ Wing، 1988). با این حال، با توجه به گفته های Bryant و Budd (1984)، تسلط موفق بر این مهارت اجتماعی می تواند به شانس بیشتری برای تعاملات اجتماعی مثبت با همسالان منجر شود. در واقع، برخی تصور می کنند که تسهیم یک بخش اساسی از بازی تعاملی بین همسالان است. (Bryant و Budd، 1984؛ DeQuinzio، Townsend، و Poulson، 2008).

مطالعات زیادی روی افزایش مهارت های تسهیم در کودکان در حال رشد و کودکان مبتلا به ASD متمرکز شده اند. به عنوان مثال، Barton و Ascione (1979) رفتار تسهیم نمایش داده شده توسط کودکان نوعاً در حال رشد پیش دبستانی را با پیاده سازی یک بسته درمانی افزایش دادند که شامل دستورالعمل ها، مدل سازی، تمرین رفتار، برانگیختگی های سریع، و تقویت اجتماعی بود. Bryant و Budd (1984) یافته های Barton و Ascione (1979) را با استفاده از همان بسته آموزشی برای افزایش رفتارهای تسهیم و کاهش رفتارهای غیر تسهیم نمایش داده شده توسط شرکت کنندگانی مانند کودکان پیش دبستانی با معلولیت رفتاری گسترش دادند. معرفی بسته های آموزشی به افزایش رفتارهای تسهیم و کاهش رفتارهای غیر تسهیم برای پنج نفر از شش فرزند پیشنهاد شده منجر شد.

Sawyer، Luiselli، Ricciardi، و Gower (2005) یک بسته مداخله را پیاده سازی نمودند که شامل یک روش تحریک قبل از جلسه بازی، اعلان، و تقویت مشروط اجتماعی برای افزایش تسهیم نمایش داده شده توسط یک کودک مبتلا به ASD بود. این بسته شامل یک مربی تبیین کننده اهمیت تسهیم برای شرکت کنندگان، این مربی و یک همسال شرکت کننده برای مدل سازی رفتار تسهیم مناسب، شرکت کننده ای برای تمرین رفتار تسهیم با مربی و همسال، و شرکت کننده ای برای دریافت بازخورد از مربی با اعلان و ستایش مشروط در سراسر تمرینات بود. زمانی که کل بسته درمان پیاده سازی شد، رفتارهای تسهیم شرکت کننده از سطوح پایه ارتقا یافت. هنگامی که روش تحریک در طول مرحله دوم درمان برداشته شد، تسهیم شرکت کننده کاهش یافت، که نشان می داد روش تحریک برای افزایش تسهیم نمایش داده شده توسط شرکت کننده لازم است.

DeQuinzio و همکاران. (2008) مطلوبیت یک روش زنجیره ای را برای افزایش رفتار تسهیم نمایش داده شده توسط چهار کودک مبتلا به ASD نشان دادند. زنجیره رفتار تسهیم شامل دنباله ای از پاسخ های بازی بود. این زنجیره پاسخ تسهیم در سراسر اسباب بازی های متعدد با استفاده از اعلان شنوایی از صدای ضبط ها، هدایت دستی، و دسترسی مشروط به بازی با اسباب بازی و تعامل معلم در طول جلسات مداخله آموزش داده شد. رفتار تسهیم در حضور همسالان ارتقا یافت و در یک محیط جدید به اسباب بازی های جدید تعمیم داده شد.

Marzullo-Kerth و همکاران. (2011) یافته های DeQuinzio و همکاران (2008) را با پیشنهادات آموزشی برای تسهیم به نمایش گذاشته توسط چهار کودک مبتلا به ASD در سراسر چندین کلاس با چند نمونه گسترش دادند. (به عنوان مثال، موارد هنری، اسباب بازی، مواد باشگاهی، و غذاهای سرپایی). این مداخله شامل یک روش تصحیح خطا بود که شامل یک مدل ویدئویی، برانگیختگی های سریع شنوایی و جسمی، و تقویت مشروط رمزی برای تسهیم پیشنهادات بود. همه چهار فرزند پیشنهادات تسهیم خود را در طول مداخله و پیشنهادات تسهیم تعمیم یافته به محرک جدید، یک محیط جدید، و حضور همسالان و بزرگسالان جدید افزایش دادند. یکی از شرکت کنندگان، تعمیم تسهیم را در سراسر رده ها نشان داد و همه شرکت کنندگان تعمیم تسهیم را در این رده ها نمایش دادند.

در حالی که بسته های درمانی مشخص نموده اند که می توان با موفقیت رفتار تسهیم را افزایش داد، پژوهش کمتری در ارتباط با شرایطی که تحت آن تسهیم مستقل رخ می دهد، به خصوص برای کودکان مبتلا به ASD انجام شده است. برخی از کودکان ممکن است رفتار تسهیم را در کارنامه رفتاری خود هرگز نداشته باشند. دیگر کودکان ممکن است رفتار تسهیم را نشان دهند، البته به شیوه ای متناقض. برای این گروه اول کودکان، آموزش رفتار تسهیم با استفاده از بسته های درمان مذکور ممکن است موثر باشد. برای این گروه دوم از کودکان، مداخله ممکن است قادر به تقویت کارآمد تر نمایش رفتار مورد نظر در شرایطی شود که به طور معمول با تسهیم مرتبط نیستند. یک متغیر محتمل که ممکن است رفتار تسهیم را تحت تاثیر قرار دهد، اولویت محرک به اشتراک گذاشته شده است. نشان داده شده است که حذف محرک ترجیح داده شده می تواند برای رفتار مشکل نمایش داده شده توسط بعضی از افراد معلول تحریک کننده باشد (Kang و همکاران، 2010، 2011). بنابراین، برخی از حس های شهودی را ایجاد می کند که صرفه نظر نمودن دسترسی مستقل به محرک اولویت بالا (به عنوان مثال، تسهیم) ممکن است سخت باشد.

بنابراین، هدف از مطالعه 1 در پژوهش حاضر، ارزیابی اثر اولویت محرک روی سطح کمک یا اعلان (مستقل، حرکات و اشارات، کلامی، و یا فیزیکی) مورد نیاز برای پاسخ به درخواست و تسهیم آیتم ها با همسال بود. فرضیه مطالعه 1 این بود که شرکت کنندگان به یک سطح بالاتر از اعلان و یا کمک برای پاسخ به درخواست همسال به منظور تسهیم یک آیتم اولویت-بالا نسبت به سطح اعلان یا کمک مورد نیاز برای پاسخ به یک درخواست برای تسهیم یک آیتم با اولویت کم نیاز دارند. مطالعه 2 برای ارزیابی اثربخشی مداخله مبتنی بر رمز برای افزایش تسهیم مستقل طراحی شده بود، با اینکه کمک و یا اعلان برای موفقیت تسهیم در طی مطالعه 1 لازم بود.

ABSTRACT

The current studies evaluated variables affecting sharing exhibited by children with autism spectrum disorder. Study 1 evaluated the effects of manipulating item preference on the level of assistance needed to exhibit sharing behavior for 4 children with autism. Item preference clearly affected 2 participants’ percentage of independent sharing. Preference did not have as clear of an effect for a third participant. However, sharing a high-preference item generally required a higher level of prompting (e.g., vocal prompts) to share. The fourth participant’s percentage of independent sharing was not influenced by preference, and his independent sharing behavior was similar across item preference. Study 2 assessed the effectiveness of a token reinforcement procedure as an intervention designed to increase independent sharing of high-preference items for the two participants who did not independently share those items during Study 1. Independent sharing increased for both participants when the token procedure was in place and decreased when it was removed.

Children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience qualitative impairments in communication and social interaction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These persistent deficits make everyday interactions between individuals with ASD and their peers and care givers challenging. One essential skill for young children to learn to develop relationships with peers and to participate in appropriate social interactions is sharing. Sharing, or responding to requests to share, is a social skill that children with ASD struggle to master (Baron-Cohen, Leslie, & Frith, 1985; Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998; Marzullo-Kerth, Reeve, Reeve, & Townsend, 2011; Rheingold & Hay, 1980; Rutter, 1978; Volkmar, Carter, Sparrow, & Cicchetti, 1993; Wing, 1988). However, according to Bryant and Budd (1984), successful mastery of this social skill might result in more chances for positive social interactions with peers. In fact, some consider sharing to be a fundamental part of interactive play between peers (Bryant & Budd, 1984; DeQuinzio, Townsend, & Poulson, 2008).

Several studies have focused on increasing sharing repertoires in typically developing children and children with ASD. For example, Barton and Ascione (1979) increased the sharing behavior exhibited by typically developing preschool children by implementing a treatment package that included instructions, modeling, behavior rehearsal, prompting, and social reinforcement. Bryant and Budd (1984) extended the findings of Barton and Ascione (1979) by using the same training package to increase sharing behaviors and decrease nonsharing behaviors exhibited by participants described as preschool children with behavioral handicaps. The introduction ofthe training package resulted in an increase in sharing behaviors and suggested decreases in nonsharing behaviors for five out of six children.

Sawyer, Luiselli, Ricciardi, & Gower (2005) implemented an intervention package that included a priming procedure before play sessions, prompting, and contingent social reinforcement to increase sharing exhibited by a child with ASD. The package consisted of the instructor explaining the importance of sharing to the participant, the instructor and a peer of the participant modeling appropriate sharing behaviors,the participant rehearsing sharing behaviors with the instructor and the peer, and the participant receiving feedback from the instructor with prompting and contingent praise throughout the rehearsals. The participant’s sharing behaviors increased from baseline levels when the entire treatment package was implemented. When the priming procedure was removed during a second treatment phase, the participant’s sharing decreased, suggesting that the priming procedure was necessary to increase sharing exhibited by the participant.

DeQuinzio et al. (2008) demonstrated the utility of a forward chaining procedure to increase sharing behavior exhibited by four children with ASD. The sharing behavior chain consisted of a sequence of show–give–play responses. This sharing response chain was taught across multiple toys using auditory prompting from voice-recorders, manual guidance, and contingent access to toy play and teacher interaction during intervention sessions. Sharing behavior increased in the presence of peers and generalized to novel toys in a new setting.

Marzullo-Kerth et al. (2011) extended the findings of DeQuinzio et al. (2008) by training offers to share exhibited by four children with ASD across several multiple-exemplar classes (e.g., art materials, toys, gym materials, and snack foods). The intervention included an error-correction procedure that consisted of a video model, auditory and physical prompts, and contingent token reinforcement for correct offers to share. All four children increased their offers to share during intervention, and offers to share generalized to novel stimuli, a new setting, and the presence of new peers and adults. One participant showed generalization of sharing across categories, and all participants displayed generalization of sharing within categories.

While treatment packages have been identified that can successfully increase sharing behavior, less research has been conducted related to the conditions under which independent sharing occurs, particularly for children with ASD. Some children may not have sharing behavior in their behavioral repertoire at all. Other children may exhibit sharing behavior, albeit in an inconsistent manner. For this first group of children, teaching sharing behavior using the aforementioned treatment packages may be effective. For this second group of children, intervention may be able to be more streamlined and consist simply of reinforcement for exhibiting the desired behavior under conditions not typically associated with sharing. One likely variable that may affect sharing behavior is the preference of the stimulus to be shared. Removal of preferred stimuli has been demonstrated to be evocative of problem behavior exhibited by some individuals with developmental disabilities (Kang et al., 2010, 2011). Thus, it makes some intuitive sense that independently giving up access to highpreference stimuli (i.e., sharing) may be difficult.

Thus, the purpose of Study 1 in the current investigation was to evaluate the effect of stimulus preference on the level of assistance or prompting (independent, gestural, verbal, or physical) needed to respond to a peer’s request and share items. The hypothesis of Study 1 was that the participants would require a higher level of prompting or assistance to respond to a peer’s request to share a high-preference item compared to the level of prompting or assistance needed to respond to a request to share a low-preferred item. Study 2 was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a token economy-based intervention to increase independent sharing if assistance or prompting was needed to successfully share during Study 1.

چکیده

1. روش ها: مطالعه 1

1.1. شرکت کنندگان

1.2. محیط و مواد

1.3. متغیرهای وابسته

1.4. جمع آوری داده ها و توافق ناظر داخلی

1.5. روش ها و طراحی تجربی

2. نتایج و بحث: مطالعه 1

3. روش ها: مطالعه 2

3.1. شرکت کنندگان

3.2. محیط و مواد

3.3. متغیر وابسته

3.4. جمع آوری داده ها و توافق ناظر

3.5. طراحی و روش تجربی

4. نتایج و بحث: مطالعه 2

5. بحث کلی

Abstract

1. Methods: study 1

1.1. Participants

1.2. Setting and materials

1.3. Dependent variables

1.4. Data collection and interobserver agreement

1.5. Procedures and experimental design

2. Results and discussion: study 1

3. Methods: study 2

3.1. Participants

3.2. Settings and materials

3.3. Dependent variable

3.4. Data collection and interobserver agreement

3.5. Experimental design and procedures

4. Results and discussion: study 2

5. General discussion

References