دانلود رایگان مقاله تاثیر فرهنگ سازمانی بر یکپارچگی زنجیره تامین

چکیده

هدف- این مطالعه با هدف پر کردن شکاف در درک آثار فرهنگ سازمانی بر یکپارچگی زنجیره تامین (SCI) صورت گرفته است و این کار با بررسی روابط بین فرهنگ های سازمانی و SCI صورت گرفته است. مطالعات موجود در مورد بررسی سوابق SCI عمدتاً بر محیط ها, روابط داخل شرکت و دیگر عوامل در سطح شرکت تمرکز می نمایند. این مطالعات به طور کلی به فرهنگ سازمانی نگاه نموده اند. مطالعات کمی که آثار فرهنگ سازمانی بر SCI را بررسی نموده اند, یافته های ناسازگاری را نشان داده اند.

طراحی/ روش شناسی/رویکرد- با قرار دادن فرهنگ سازمانی در چارچوب رقابتی ارزش (CVF), این مطالعه یک مدل مفهومی را برای روابط بین فرهنگ سازمانی و SCI ایجاد می کند. این مطالعه از رویکرد اقتضایی و رویکرد پیکربندی برای بررسی روابط پیشنهادی با استفاده از داده های جمع آوری شده از 317 تولیدکننده در سراسر 10 کشور استفاده می کند.

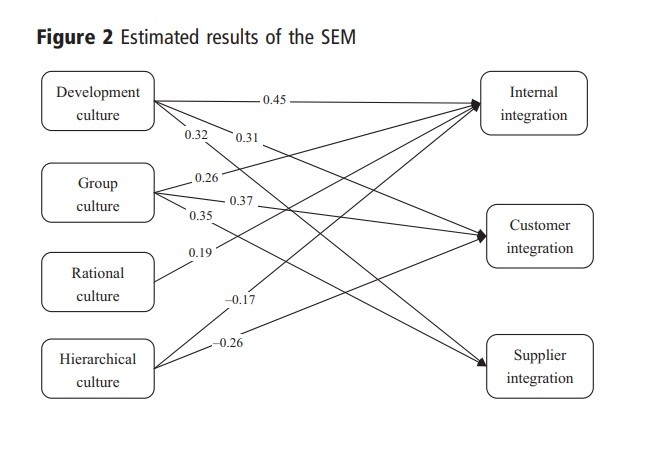

یافته ها- نتایج احتمالی نشان می دهد که فرهنگ توسعه و گروهی به طور مثبت با تمام سه بعد SCI در ارتباط هستند. با این حال, فرهنگ عقلانی به طور مثبت تنها به یکپارچگی داخلی مرتبط است و فرهنگ سلسله مراتبی به طور منفی به ادغام مشتری و داخلی مرتبط است. رویکرد پیکربندی, چهار مشخصه از فرهنگ سازمانی را شناسایی می کند: مشخصات سلسله مراتبی, انعطاف پذیر, یکسانی و سطحی. مشخصه یکسان, بالاترین سطح از توسعه, فرهنگ های گروهی و عقلانی و کمترین سطح از فرهنگ سلسله مراتبی را نشان می دهد. مشخصه یکسان, همچنین دارای بالاترین سطوح از ادغام داخلی, مشتری و تامین کننده است.

محدودیت ها/پیامدهای پژوهش- این مطالعه تحت چندین محدودیت قرار دارد. از نظر تئوری, این مطالعه تمام ناسازگاری ها در رابطه بین فرهنگ سازمانی و SCI را حل و فصل نمی کند. از نظر روش شناسی, این مطالعه از داده های سطح مقعی از تولیدکنندگان با عملکرد-عالی استفاده می کند. چنین داده هایی نمی توانند توضیحات قوی در مورد علت و معلول را فراهم نمایند, بلکه تنها یافته هایی کلی و سطحی را ارائه می دهند.

پیامدهای عملی- این مطالعه به مدیران یادآوری می کند تا در هنگام پیاده سازی SCI, فرهنگ سازمانی را در نظر گیرند. این مطالعه همچنین سرنخ هایی را برای کمک به مدیران در ارزیابی و تنظیم فرهنگ سازمانی برای SCI فراهم می کند.

ارزش/ اصالت- این مطالعه دو سهم نظری را در این حوزه دارا است. اولاً, با بررسی روابط بین فرهنگ سازمانی و SCI در یک زمینه جدید, یافته های این مطالعه, شواهدی اضافی را برای وفق دادن یافته های ناسازگار با این موضوع فراهم می کند. دوماً, صرفه نظر از کار قبلی بررسی ابعاد خالص فرهنگ سازمانی, این مطالعه یک رویکرد اقتضایی و پیکربندی ترکیبی را برای پرداختن به آثار فردی و جمعی تمام ابعاد فرهنگ سازمانی اتخاذ می کند. این رویکرد جامع تر, درک ما را از روابط بین فرهنگ سازمانی و SCI قوی می کند.

1. مقدمه

یکپارچگی زنجیره تامین (SCI) یا توسعه همکاری راهبردی درون شرکتی یا بین شرکتی در طول زنجیره تامین (Zhao et al., 2008) به طور گسترده به عنوان یک راهبرد مهم برای بهبود عملکرد شرکت مد نظر قرار گرفته است (Flynn et al., 2010; Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001; Koufteros et al., 2005; Vickery et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2011). هرچند, پیاده سازی SCI آسان نیست, زیرا به سرمایه گذاری های خاص در میان شرکای زنجیره تامین نیاز دارد که اغلب پیچیده و دارای ریسک است (Wu et al., 2004). نوشته های مدیریت راهبردی نشان داده اند که اتحادیه های راهبردی که جنبه های مهم از SCI هستند (Zhao et al., 2011) دارای نرخ شکست بالایی هستند (Das and Teng, 1999; Park and Ungson, 2001; Whipple and Frankel, 2000). نوشته های SCI نیز نشان داده اند که ادغام کامل تامین کنندگان و مشتریان با یکدیگر نادر است و نتایج دور از ایده آل است (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Fawcett and Magnan, 2002; Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001). بنابراین, به منظور تسهیل پیاده سازی SCI, شناسایی عوامل درگیر و اثرات آنها بر SCI لازم است (Fawcett and Magnan, 2002).

در میان سوابق ممکن از SCI, ما به طور خاص به فرهنگ سازمانی علاقه مند هستیم که به عنوان ارزش ها یا باورها مشترک در میان اعضای یک سازمان تعریف می شود (Schein, 2004; Zu et al., 2010). دو دلیل برای تمرکز بر فرهنگ سازمانی وجود دارد. اولاً, فرهنگ سازمانی نسبت به عوامل دیگر مانند فناوری یا اطلاعات دارای انعطاف پذیری کمتری است (Schein, 2004; Zu et al., 2010 et al., 2005). ثانیاً, فرهنگ سازمانی, نقش مهمی در مدیریت زنجیره تامین ایفا می کند (SCM) (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Dowty and Wallace, 2010; Fawcett et al., 2008). فرهنگ سازمانی مناسب از نظر تسهیم اطلاعات, کار تیمی و اتخاذ ریسک بر رفتار کارمندان داخلی تاثیر می گذارد (McCarter et al., 2005). فرهنگ سازمانی در حوزه هایی چون مهارت های رابطه و اعتماد, بر رفتار درون شرکتی تاثیر می گذارد (Beugelsdijk et al., 2006; Schilke and Cook, 2014). چنین مهارت های مرتبط با فرهنگ سازمانی برای موفقیت SCI مهم هستند (Fawcett et al., 2008; McAfee et al., 2002; McCarter et al., 2005; Whitfield and Landeros, 2006). زمانی که حمایت از فرهنگ سازمانی مناسب وجود ندارد, احتمالاً شرکت ها به اهداف خود دست نمی یابند. مثلاً, به علت برخوردهای (تناقضات) فرهنگ سازمانی داخلی, شرکت های اروپایی تابعه ژاپن برخی اوقات موفقیت به ارائه خدمات تحویل رضایت بخش نمی شوند (de Koster and Shinohara, 2006).

با توجه به اهمیت فرهنگ سازمانی برای SCM, مطالعات قبلی به طور گسترده به بررسی رابطه بین فرهنگ سازمانی و SCI پرداخته اند (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Naor et al., 2008; Zu et al., 2010). بیشتر این مطالعات از چارچوب ارزش رقابتی (CVF) استفاده نموده اند که توسط Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) برای نشان دادن فرهنگ سازمانی پیشنهاد شده است. CVF شامل چهار بعد می شود, یعنی, ابعاد فرهنگ توسعه, گروهی, سلسله مراتبی و عقلانی. مطالعات مبتنی بر CVF, ارتباطاتی بین این ابعاد مختلف فرهنگ سازمانی و ابعاد مختلف SCI ایجاد نموده اند (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Naor et al., 2008; Zu et al., 2010). هرچند, دو شکاف در این مطالعات موجود باقی می ماند.

اولاً, یافته های مطالعات موجود سازگار نیستند, حتی با اینکه آنها از تعاریف مشابه فرهنگ گروهی استفاده نموده اند. به طور مثال, Naor et al. (2008) دریافته اند که فرهنگ گروهی به طور مثبت مرتبط با درگیری مشتری و تامین کننده است که دو جنبه مهم از SCI هستند. با این حال, Braunscheidel et al. (2010) دریافتند که فرهنگ گروهی نه مرتبط با ادغام تامین کننده (SI) است و نه مرتبط با ادغام مشتری (CI). Zu et al. (2010) گزارش دادند که فرهنگ سلسله مراتبی, نه مرتبط با روابط مشتری است و نه تامین کننده و Braunscheidel et al. (2010) نشان دادند که فرهنگ سلسله مراتبی به طور منفی مرتبط با SI و CI است.

ثانیاً, مطالعات موجود تنها به بررسی آثار فردی هر بعد متفاوت از فرهنگ سازمانی بر SCI پرداخته اند و به آثار مشترک این ابعاد نپرداخته اند (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Naor et al., 2008; Zu et al., 2010). برای مثال, Braunscheidel et al. (2010) آثار فردی چهار بعد فرهنگی را بر SCI به طور جداگانه بدون بررسی آثار همکاری آنها در فرهنگ سازمانی مورد بررسی قرار دادند. در حقیقت, این محدودیت در بیشتر مطالعات فرهنگ سازمانی که مرتبط با CVF می باشد متداول است (Leisen et al., 2002; McDermott and Stock, 1999; Nahm et al., 2004; Prajogo and McDermott, 2005; Stock et al., 2007; Zu et al., 2010). در بررسی اخیر از نوشته ها در مورد CVF, Hartnell et al. (2011 و صفحه 687) نشان دادن که بیشتر مطالعای که از CVF استفاده نموده اند, تنها به بررسی ارتباط مستقل انواع فرهنگ ها با معیارهای اثربخشی پرداخته اند و به تعامل همکارانه در میان ارزش هایی که فرهنگ سازمان را تعریف می کنند نپرداخته اند و روابط بین ابعاد فرهنگی مرتبط را که با هم برای حمایت یا ممانعت از اقدامات SCM کار می کنند نادیده گرفته اند. (Dowty and Wallace, 2010). این رویکرد گسسته نتوانسته است به درستی تاثیر فرهنگ سازمانی را منعکس نماید (Flynn et al., 2010; Hult et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 1993; Miller, 1986). به امید اجتناب از این مسئله در آینده, بسیاری از محققان, پژوهش های بیشتری را نموده اند که از رویکرد پیکربندی برای در نظر گرفتن ابعاد فرهنگ در هم تنیده استفاده می کند (Detert et al., 2000; Hartnell et al., 2011; Stock et al., 2007; Zu et al., 2010).

این مطالعه با پاسخ به دو سوال پژوهشی به دنبال پرداختن به این شکاف ها در مطالعات قبلی است:

RQ1: چگونه چهار بعد فرهنگ سازمانی به طور یک به یک بر SCI تاثیر می گذارند؟

RQ2: چگونه این چهار بعد به طور مشترک بر SCI تاثیر می گذارند؟

برای پاسخ به این سوالات, ما پژوهش پیمایشی را در زمینه ای جدید با تولیدکنندگان دارای عملکرد-عالی (HPMs) در 10 کشور انجام دادیم. با مجموعه داده های برگرفته از مشارکت این شرکت ها و اتخاذ یک رویکرد اقتضایی, بررسی نمودیم که چگونه چهار بعد فرهنگ سازمانی (فرهنگ توسعه, گروهی, سلسله مراتبی و عقلانی) به سه بعد SCI (SI, II و CI) مرتبط می شوند. همچنین ما وضوح این روابط را از طریق استفاده از مدلسازی معادله الگوی (SEM) مد نظر قرار دادیم. بنابراین, با اعمال یک رویکرد پیکربندی, هدف ما, شناسایی مشخصات فرهنگ سازمانی مختلف و بررسی نحوه تغییر ابعاد SI, II و CI در سراسر مشخصات فرهنگی مختلف است. با پاسخ به سوالات پژوهشی خود, با دو روش به نوشته های SCI کمک خواهیم نمود.

Abstract

Purpose – This study aims to bridge the gap in understanding the effects of organizational culture on supply chain integration (SCI) by examining the relationships between organizational cultures and SCI. The extant studies investigating the antecedents of SCI focus mainly on environments, interfirm relationships and other firm-level factors. These studies generally overlook the role of organizational culture. The few studies that do examine the effects of organizational culture on SCI show inconsistent findings.

Design/methodology/approach – By placing organizational culture within the competing value framework (CVF), this study establishes a conceptual model for the relationships between organizational culture and SCI. The study uses both a contingency approach and a configuration approach to examine these proposed relationships using data collected from 317 manufacturers across ten countries.

Findings – The contingency results indicate that both development and group culture are positively related to all three dimensions of SCI. However, rational culture is positively related only to internal integration, and hierarchical culture is negatively related to both internal and customer integration. The configuration approach identifies four profiles of organizational culture: the Hierarchical, Flexible, Flatness and Across-the-Board profiles. The Flatness profile shows the highest levels of development, group and rational cultures and the lowest level of hierarchical culture. The Flatness profile also achieves the highest levels of internal, customer and supplier integration.

Research limitations/implications – This study is subject to several limitations. In theoretical terms, this study does not resolve all of the inconsistencies in the relationship between organizational culture and SCI. In terms of methodology, this study uses cross-sectional data from high-performance manufacturers. Such data cannot provide strong causal explanations, but only broad and general findings.

Practical implications – This study reminds managers to consider organizational culture when they implement SCI. The study also provides clues to help managers in assessing and adjusting organizational culture as necessary for SCI.

Originality/value – This study makes two theoretical contributions. First, by examining the relationships between organizational culture and SCI in a new context, the findings of the study provide additional evidence to reconcile the previously inconsistent findings on this subject. Second, by departing from the previous practice of investigating only particular dimensions of organizational culture, this study adopts a combined contingency and configuration approach to address both the individual and synergistic effects of all dimensions of organizational culture. This more comprehensive approach deepens our understanding of the relationship between organizational culture and SCI.

1. Introduction

Supply chain integration (SCI), or the development of strategic intrafirm and interfirm collaboration along the supply chain (Zhao et al., 2008), has been widely regarded as an important strategy for improving firm performance (Flynn et al., 2010; Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001; Koufteros et al.,2005; Vickery et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2011). However, the implementation of SCI is not easy, as it requires mutual adaptation and relation-specific investments among supply chain partners, which are often quite complicated and risky (Wu et al., 2004). The strategic management literature indicates that strategic alliances, which are important aspects of SCI (Zhao et al., 2011), have a high failure rate (Das and Teng, 1999; Park and Ungson, 2001; Whipple and Frankel, 2000). The SCI literature also suggests that full integration with suppliers and customers is rare, and the results can be far from ideal (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Fawcett and Magnan, 2002; Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001). Thus, to facilitate the implementation of SCI, it is necessary to the identify factors involved and their effects on SCI (Fawcett and Magnan, 2002).

Among the possible antecedents of SCI, we are particularly interested in organizational culture, which is defined as the values or beliefs shared by members of an organization (Schein, 2004; Zu et al., 2010). There are two reasons for focusing on organizational culture. First, organizational culture is more intractable than other factors such as technology or information (Fawcett et al., 2008; McCarter et al., 2005). Second, organizational culture plays an important role in supply chain management (SCM) (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Dowty and Wallace, 2010; Fawcett et al., 2008). Appropriate organizational culture influences the behavior of internal employees in terms of information sharing, teamwork and risk taking (McCarter et al., 2005). Organizational culture also affects interfirm behavior in areas such as relationship skills and trust (Beugelsdijk et al., 2006; Schilke and Cook, 2014). Such organizational culture-related skills are important for SCI success (Fawcett et al., 2008; McAfee et al., 2002; McCarter et al., 2005; Whitfield and Landeros, 2006). When the support of an appropriate organizational culture is absent, firms may not achieve their objectives. For example, because of internal organizational culture clashes, European subsidiaries of Japanese companies have sometimes failed to provide satisfactory delivery service (de Koster and Shinohara, 2006).

Given the importance of organizational culture for SCM, previous studies have extensively examined the relationship between organizational culture and SCI (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Naor et al., 2008; Zu et al., 2010). Most of these studies have used the competing value framework (CVF) proposed by Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) to represent organizational culture. The CVF includes four dimensions, namely, the development, group, hierarchical and rational culture dimensions. Studies based on the CVF establish the links between these various dimensions of organizational culture and the different dimensions of SCI (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Naor et al., 2008; Zu et al., 2010). Nevertheless, two gaps remain in these extant studies.

First, the findings of the extant studies are not consistent, even though they use similar definitions of group culture. For example, Naor et al. (2008) find that group culture is positively related to both supplier and customer involvement, which are two important aspects of SCI. However, Braunscheidel et al. (2010) find that group culture is related to neither supplier intergration (SI) nor customer integration (CI). Zu et al. (2010) report that hierarchical culture is related to neither customer nor supplier relationships, and Braunscheidel et al. (2010) find that hierarchical culture is negatively related to both SI and CI.

Second, the extant studies examine only the individual effects of each different dimension of organizational culture on SCI, rather than the joint effects of these dimensions (Braunscheidel et al., 2010; Naor et al., 2008; Zu et al., 2010). For instance, Braunscheidel et al. (2010) examine the individual effects of the four cultural dimensions on SCI separately, without investigating their synergistic effects on organizational culture simultaneously. In fact, this limitation is prevalent in most studies of organizational culture that involve the CVF (Leisen et al., 2002; McDermott and Stock, 1999; Nahm et al., 2004; Prajogo and McDermott, 2005; Stock et al., 2007; Zu et al., 2010). In a recent review of literature on the CVF, Hartnell et al. (2011, p. 687) find that most studies using CVF examine only the “culture types’ independent association with effectiveness criteria”, but not the “synergistic interaction among the values that define an organization’s culture” ignore the relationships between closely related cultural dimensions that work together collectively to support or hinder SCM practices (Dowty and Wallace, 2010). This fragmented approach may fail to correctly reflect the true influence of organizational culture in a holistic way (Flynn et al., 2010; Hult et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 1993; Miller, 1986). In the hope of avoiding this problem in the future, many researchers call for further research that uses a configuration approach to consider the interwoven cultural dimensions simultaneously (Detert et al., 2000; Hartnell et al., 2011; Stock et al., 2007; Zu et al., 2010).

This study seeks to address these gaps in previous studies by answering two research questions: RQ1: How do the four organizational culture dimensions influence SCI individually?

RQ2: How do the four culture dimensions jointly influence SCI?

To answer these questions, we conduct survey research in a new context with high-performance manufacturers (HPMs) in ten countries. With a dataset drawn from the participating HPMs and by taking a contingency approach, we investigate how the four dimensions of organizational culture (development, group, hierarchical and rational culture) are related to the three dimensions of SCI (SI, II and CI). We also intend to clarify these relationships through the use of structural equation modeling (SEM). Then, applying a configuration approach, we aim to identify various organizational culture profiles and investigate how the dimensions of SI, II and CI vary across different culture profiles. By answering our research questions, we contribute to the SCI literature in two ways.

چکیده

1. مقدمه

2. پیش زمینه نظری و مدل مفهومی

2.1 یکپارچگی زنجیره تامین

2.2 فرهنگ سازمانی و CVF [2]

2.3 رویکرد اقتضایی و پیکربندی

2.4 اثرات فرهنگ سازمانی بر SCI

3. توسعه فرضیه ها

3.1 فرهنگ توسعه و SCI

3.2 فرهنگ گروهی و SCI

3.3 فرهنگ عقلانی و SCI

3.4 فرهنگ سلسله مراتبی و SCI

3.5 مشخصات فرهنگ سازمانی و SCI

4. روش شناسی

4.1 جمع آوری داده ها

4.2 طراحی پرسشنامه

4.3 توسعه اندازه گیری

5. تحلیل و نتایج

5.1 نتایج رویکرد اقتضائی

5.2 نتایج رویکرد پیکربندی

5.3 نتایج ترکیبی رویکردهای اقتضایی و پیکربندی

6. بحث و بررسی

6.1 کمک های نظری

6.2 پیامدهای مدیریت

6.3 محدودیت ها و تحقیقات آینده

7. نتایج

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical background and the conceptual model

2.1 Supply chain integration

2.2 Organizational culture and CVF[2]

2.3 Contingency and configuration approach

2.4 The effects of organizational culture on SCI

3. Hypotheses development

3.1 Development culture and SCI

3.2 Group culture and SCI

3.3 Rational culture and SCI

3.4 Hierarchical culture and SCI

3.5 Organizational culture profiles and SCI

4. Methodology

4.1 Data collection

4.2 Questionnaire design

4.3 Measurement development

5. Analysis and results

5.1 Results of the contingency approach

5.2 Results of the configuration approach

5.3 Combined results of the contingency and

configuration approaches

6. Discussion

6.1 Theoretical contributions

6.2 Managerial implications

6.3 Limitations and future research

7. Conclusions