دانلود رایگان مقاله پیاده سازی حسابداری تعهدی در بخش دولتی

چکیده

این مقاله با استفاده از نظریهی مبسوطِ نهادیِ جدید، در تلاش است تا نظرات حسابداران، متصدیان بودجه و سیاستگذارانی را که در پیادهسازی حسابداری تعهدیِ بخش دولتی در کشورهای مختلف عضو OECD دخیل هستند، منعکس سازد. نظراتِ کنشگران سازمانی و چالشهایی را که آنها در فرایند پیاده سازی حسابداری تعهدی و بودجه بندی در محیط های خاص شان مواجه هستند، در نشریات پژوهشیِ مرتبط با حسابداری تعهدیِ بخش دولتی،دیده و شنیده نمیشوند. یافتههای تجربیِ این پژوهش بیانگر این است که ابهامات سیاسی و فنی که در پیاده سازیِ حسابداری بخش دولتی در کشورهای مختلف وجود دارند، بسیار گسترده تر از چیزی هستند که در کارهای دانشگاهی ترسیم شده اند و در گزارش ها و پژوهش های طرفداران حسابداری تعهدی وجود دارند. وقتی که این چالشها به سطح سازمان تسری پیدا کرد، سردرگمی و عدمقطعیتی را در میان متصدیان بودجه و خزانه ایجاد کرد؛ یعنی میان کسانی که به حسابداری تعهدی بخش دولتی در حوزه های خاص شان می پردازند و مشروعیت سطح سازمانی را تهدید می کنند. بنابراین ارتباط و تشریکمساعی بیشتر میان کنشگران در سطوح سازمانی، حوزهی سازمانی و نهادی، جهت ایجاد مجموعه ی جدیدی از دانش و معلومات برای تسهیل حسابداری تعهدیِ بخش دولتی در میان کشورها، مورد نیاز میباشند.

1. مقدمه

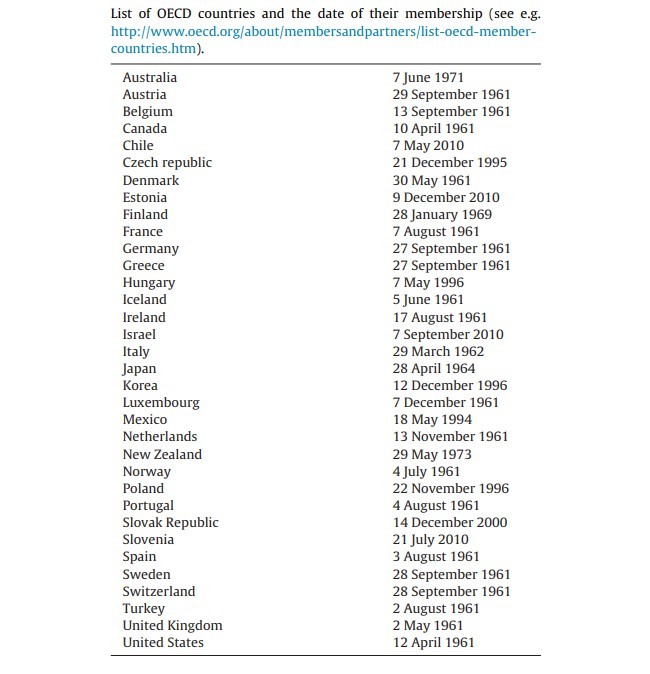

هدف از این مقاله، واکاویِ چالشهای عمدهایست که در فرایند پیادهسازیِ حسابداری تعهدی در بخش دولتی در کشورهای عضو سازمان همکاری و توسعه ی اقتصادی (OECD) وجود دارند. ما به دغدغههای کنشگران اصلی در سازمان کشورهای عضوOECD می پردازیم، که اکثریت آنها حسابداران ارشدی هستند که از میان متصدیان خزانه و بودجه انتخاب شده اند، یا سیاستگذارانی هستند که از وزارتخانهها و قسمتی از بدنهی دولت انتخاب شده اند که مستقیماً در تهیه یا پیادهسازیِ حسابداریِ تعهدی و اصلاحات مرتبط با بودجهبندی در حوزهی خودشان، دخیل بودهاند.از آنجاکه اکثریت قریب به اتفاق اعضای OECD را کشورهای پیشرفته تشکیل می دهند (اعضای اتحادیهی اروپا و کاربرانِ عمده ی حسابداری و بودجهبندیِ تعهدی در سطح جهانی)، این سازمان فرصت مناسبی را جهت تحقیق روی تجارب مرتبط با حسابداری تعهدی پیش رو می گذارد. سازمان همکاری و توسعهی اقتصادی، بهترین انعکاس و آینه ای تمام عیار از روند جهانی در زمینهی حسابداریِ تعهدیِ بخش دولتی می باشد.

پیادهسازی حسابداری تعهدی توسط اعضای OECD، به بخش کلیدیِ تحقق اصلاحات مالیِ بخش دولتی تبدیل شده است، که مجموعاً از آن با عنوان «مدیریت دولتیِ نوین (NPM)» و «مدیریت نوینِامور مالیِ دولتی(NPFM)» نام برده می شود. سازمان OECD بعنوان بخشی از فرایند بهبودِ حاکمیت بخش دولتی، از اتخاذ حسابداری تعهدی توسط کشورهایی که عضو این سازمان هستند حمایت کرده است. تلاش کشورهای عضو در جایگزین کردن حسابداری تعهدی به جای حسابداری نقدی، اجتنابناپذیر تلقی میشود. تاکیدات مشابهی در ارتباط با برتری حسابداری تعهدی بر حسابداری بودجهای، بلحاظ شفافیت در تخصیص منابع، شناساییِ هزینههای فعالیتهای دولت و آمار باکیفیتِ بالا - یعنی آمار مالی دولت (GFS) و سیستم حسابهای اروپایی (ESA)، که برای تصمیمات مالی و هزینهای بسیار مهم هستند- توسط سازمانهای بین المللی انجام گرفتهاند (سازمانهایی نظیر صندوق بینالمللی پول و بانکجهانی)، سیاستگذران منطقهای (مثلاً کمیسیون اروپا)، استانداردگذارانِ بینالمللی در زمینه ی حسابداری و حسابرسی (IPSAS) (مثلاً فدراسیون بینالمللیِ حسابداران (IFAC) و EUROSTAT) و انجمنهای حرفهایِ حسابداری و شرکتهای حسابداری (CIPA) (فدراسیون حسابداران اروپا (FEE)، انجمن رسمیِ حسابداران و امور مالی (CIPFA))، همگی از طرفدارانِ عمدهی حسابداری تعهدی در بخش دولتی بشمار میروند.

علیرغم این پشتیبانی و حمایتی که شرکتهای فوق از حسابداری تعهدی انجام دادهاند، در عین حال نسبت به پیادهسازی آن نیز تذکرات و هشدارهایی داده اند که عبارتند از: در نظر گرفتن ابهامات فنی و مقادیر منابع و تخصصی که کشورها باید برای پیادهسازیِ آن در اختیار داشته باشند. مثلاً انجمنهای حرفه ای، استانداردگذاران و شرکتهای حسابرسی یا حسابداران، شروطی را در خصوص اتخاذ حسابداری تعهدی و استانداردهای بینالمللیِ حسابداری بخش دولتی وضع کردهاند که کشورهای عضو اتحادیهی اروپا باید آنها را رعایت نمایند. در میان جامعه ی آکادمیک، حرکت به سوی حسابداری تعهدی، یک مسیر اصلاحاتِ مورد مناقشه بوده است. برخی از اهالیِ دانشگاه ظاهراً در خصوص منافع حسابداری تعهدی متقاعد شده اند، اما سایرین نگرانی هایی در خصوص ربط مندیِ حسابداری تعهدیِ شِبهتجاری در شرکتهای دولتی -که از اهداف و کانتکستهای مختلف برخوردارند- مطرح کرده اند. دیدگاه گروه دوم این است که پیادهسازیِ حسابداری تعهدی، بیش از اینکه منبعث از دلایل مرتبط با کارآمدی باشد، منبعث از دلایل مرتبط با مشروعیت و قانونیبودن می باشد و نیز معتقدند که در مزایای حسابداری تعهدی نیز غلو شده است.

ادعا می شود که استدلالهایی که لَه و علیهِ پیادهسازی حسابداری تعهدی در بخش دولتی مطرح می شوند –که سازمانهای بینالمللی، سیاستگذاران، استانداردگذاران، حسابداران حرفهای و اهالیِ دانشگاه مطرح میکنند-، هنجارمند هستند اما مبتنی بر شواهد نیستند.مثلاً، بین آنچه بطور نرمال از حسابداری تعهدی انتظار می رود و آنچه در عمل از پیادهسازیِ آن در سطوح مختلف سازمانی بدست آمده است، خلائی وجود دارد.با توجه به وقت و منابعی که مصروف پیادهسازیِ حسابداری تعهدی شده است، این مساله در کشورهایی نظیر استرالیا و بریتانیا مشهود است –اولین کشورهایی که حسابداری و بودجهبندیِ تعهدی را اختیار کردند.اما آنچه در نشریات پژوهشیِ مرتبط با حسابداری تعهدی در بخش دولتی غایب است، صدای کنشگرانِسطح سازمان است، که عمدتاً شامل حسابداران دولتی، متصدیان بودجه و سیاستگذارانی می باشد که بواقع در پیاده سازیِ حسابداری تعهدی دخیل هستند. پرسش هایی که هنوز در نشریات پژوهشیِ بخش دولتی به آنها پاسخی داده نشده است، شامل این پرسشها میشود: این کنشگرانِ سازمانی چگونه اصلاحات مرتبط با حسابداری تعهدیِ بخش دولتی را در محیطهای خاص به پیش می برَند، استراتژی ها و مکانیزم هایی که آنها بکار می گیرند و چالش های خاصی که در فرایند پیاده سازی با آنها روبرو هستند.

این مقاله تلاش می کند که این خلاءِ معلوماتی را که در نشریات پژوهشی وجود دارد، پر کند. ما درصدد هستیم صدای حسابداران، متصدیان بودجه و سیاستگذارانی را که در ابعاد مختلفِ حسابداری و بودجهبندی در کشورهای عضو OECD دخیل هستند، شنیده شود. این کار را از طریق نسخهی بسطیافته ی نظریه ی نهادیِ نوین که به نهادینهسازیِ نوین نیز معروف است، انجام می دهیم؛ این نسخه بطور خاص نقش عوامل میانسازمانی را در فرایند نهادیسازی تصدیق می کند. برخی ابعاد یک چارچوب را دیلارد، ریگسبای و گومان (2004) مطرح کردهاند. این زاویهی دید به ما اجازه می دهد قبل از پیادهسازی حسابداری تعهدی در محیط های خاص، روش ها و ایدههای حسابداریِ تعهدیِ بخش دولتی را که در سطوح مختلف وجود دارند، ترسیم نماییم: بویژه در سطح سیاسی و اقتصادیِ OECD)، سطح میدان سازمانی (یعنی کشورهای عضو OECD) و سطح سازمانی (یعنی کنشگرانِ کشورهای عضور OECD).

مابقیِ این مقاله به این ترتیب سازماندهی شده است. ایدههای نهادینهسازیِ نوین که لنز حساسی را جهت این پژوهش در اختیار ما می گذارد، در بخش 2 ارائه شده است. روش پژوهش را پس از آن –یعنی در بخش 3- ذکر می کنیم. بخش 4 دیدگاهها و تجاربی را بیان می کند که کشورهای عضو سازمان همکاری اقتصادی در خصوص حسابداری تعهدیِ بخش دولتی و چالش هایی که در پیادهسازی عناصر مختلفِ حسابداری تعهدی در پیادهسازیِ عناصر مختلفِ حسابداری تعهدی، بودجه بندی و IPSASها با آن روبرو بوده اند.بخش پایانی مقاله نیز در پرتوی این نظریه، به تحلیلِ پیادهسازیِ حسابداری تعهدی بخش دولتی در کشورهای عضو میپردازد و پیشنهادات را ارائه می دهد.

2. چارچوب نظری: نهادینهسازیِ مبسوطِ نوین

دانشمندان حسابداریِ بخش دولتی، در تلاش بوده اند تا با استفاده از رویکردهای جامعهشناختی مختلف، تغییرات حسابداری را تئوریزه نمایند. مثلاً تحقیقات مختلفی در زمینهی نظریهی شبکه ی کنشگران –بخصوص در زمینه ی مفهوم ترجمه- انجام گرفته است تا نحوه ی تغییرات حسابداری را و روش هایی که بواسطه ی آنها، نوآوری هایی –از طریق شبکهای از متحدان بشری و غیر بشری- در بخش مراقبت های بهداشتی و در سایر محیط های بخش دولتی رخ داده است، در قالب نظریه بیان گردد. استفاده ی گسترده از حسابداریِ تعهدی در بخش دولتی، رابطه ی اجتناب ناپذیری با ایده های نهادینهسازیِ نوین داشته است. بسیاری از ابعاد نظری، در توضیح تغییرات حسابداری با ارجاع به محیط/متغیرهای بیرونی، ناکام بوده اند؛ یعنی محیطها/متغیرهایی که در نظم دهی به روشهای حسابداری در سطح جهانی، غلبه و سیطره دارند. آنچه در نظریه ی نهادیِ نوین بطور ضمنی مطرح است، نقش سازمانها/نهادهای خارجی –مثلاً IFAC، کمیسیون اروپا و OECD- در انتشار و ترویج اصلاحات حسابداریِ بخش دولتی می باشد. بنابراین از حجمِ زیادی از نشریات پژوهشی که در مورد حسابداری بخش دولتی مطلب نوشتهاند، از نظریه ی نهادیِ نوین استفاده کرده اند و به بررسی این موضوع پرداخته اند که ایده های مشابه در زمینه ی اصلاحات (حسابداری تعهدی و IPSASها) چگونه در میان کشورهای مختلف پخش شده اند، با وجود اینکه تفاوتهای قابل توجهی در خروجی ها و نتایج این اصلاحات در آن کشورها وجود دارند.

ایدهی نهادینهسازیِ نوین، عمدتاً از مفاهیم «مشروعیت» و «ایزومورفیسم/همساختی یا همسانی» استفاده کرده است. گفته می شود که سازمانها تمایل دارند با ساختارها و هنجارهایی که بلحاظ اجتماعی پذیرفته شده اند، بعنوان بخشی از رفتار مشروعیتجویِ خودشان، خود را وفق دهند و در این فرایند به همسانی یا همساختیِ سازمانی می رسند. دیماگیو و پاوِل (1983) به سه فشار/مکانیزم اشاره می کنند که در همساختیِ سازمانی نقش دارند: اجباری، تقلیدی و هنجاری. در حالیکه مکانیزم اجباری، بویژه در بخش دولتی، به مداخله ی دولت و فشار تامینکنندگان منابع ربط داده شده است، اما مکانیزم هنجارمند بعنوان خروجیِ حرفه ای شدن تلقی شده است (مثلاً از طریق تاثیر مشاوران، دانشمندان یا افراد حرفهای). مکانیزم تقلیدی به تقلید روشهای همه-جا-حاضر در حوزهای مربوط می شود که برچسب موفقیت و مدرن بودن خورده است.نشریات پژوهشی زیادی در زمینه ی بخش دولتی از این سه مکانیزم استفاده کرده اند تا توضیح دهند که اتخاذ حسابداری تعهدی به چه نحو به یک عنصر داخلی از رفتار مشروعیت جویانه تبدیل شده است، و به این طریق مساله ی انتخابهای حسابداری درون سازمانها را روشن میسازند.اطمینان از مشروعیت، برای شرکتهای بخش دولتی یک کار الزامی بوده است، نه فقط جهت اجتناب از پرسش های مهمی که در خصوص فعالیتهایشان مطرح است، بلکه به این جهت که چهرهی آنها در کانتکست عملیاتیِ خودشان، بصورت سازمانهایی مدرن و منطقی ترسیم گردد. با اینحال، هیندمان و کانولی (2011)، از نظر دغدغههایی که کشورها/سازمانها در خصوص مشروعیت دارند، بین آنها تمایز قائل شده است. آنها استدلال می کنند که اولین کشور هایی که از حسابداریِ تعهدی در بخش دولتی استفاده کرده اند –یعنی نیوزلند، استرالیا و بریتانیا-، تا اندازهی زیادی تحت تاثیر فواید حاصل از کارآمدیِ فنیِ اقتصادی قرار داشتهاند، اما کشورهایی که بعدتر اقدام به اتخاذ حسابداریِ تعهدی کردند، بیشتر دغدغه ی مشروعیت داشتند و تقلید اضطرابِ انطباق،میزد.

Abstract

Drawing on extended new institutional theory, this paper has striven to make heard the voices of accountants, budget officers, and policy makers involved in implementing public sector accruals in different OECD member states. Such voices of the organisational actors and the challenges that they are encountering in the process of implementing accrual accounting and budgeting in their specific settings are missing in the existing public sector accruals literature. The empirical findings of the study demonstrate that the political and technical ambiguities in implementing public sector accruals across countries are much broader than outlined in the academic work and presented in the reports and studies of the proponents. Such challenges, when cascaded down to the organisational level, have brought about vast uncertainty and confusion amongst most of the budget and treasury officers who deal with public sector accruals in their specific jurisdictions, threatening the legitimacy at the organisational level. More communication and collaboration amongst the actors at institutional, organisational-field and organisational levels are therefore needed to build a coherent body of knowledge in facilitating public sector accruals reforms across countries.

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to explore the major challenges involved in implementing public sector accruals in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD) member countries.We look atthe concerns of key organisational actors of OECD member states, the majority of whom are senior accountants from treasuries and budget officers, as well as policy makers from ministries or governmental bodies directly involved in developing or implementing accrual accounting and budgeting reforms in their respective jurisdictions. The OECD represents a propitious research setting of accrual accounting experiences since the vast majority of its members are developed countries, EU members and the major adopters of accrual accounting and budgeting at a global level (Blöndal, 2003). The organisation is perhaps the best representative of a global trend in public sector accruals.

Implementing accrual accounting in OECD member states has become a key part of realising public sector financial reforms, which are collectively referred to as New Public Management (NPM) and New Public Financial Management (NPFM) reforms (Guthrie, Olson, & Humphrey, 1999; Hood, 1995). As part of improving public sector governance (Almquist, Grossi, van Helden, & Reichard, 2013), the OECD has advocated the adoption of accrual accounting for its member countries Member states’ attempts at replacing their cash accounting with accrual accounting are considered to be inevitable, particularly in the evolving sovereign debt crisis. Such efforts are hailed as major achievements in managing public expenditures more effectively and efficiently (Lapsley, Mussari, & Paulsson, 2009; Pollanen & Loiselle-Lapointe, 2012). Similar assertions relating to the supremacy of accrual accounting to budgetary accounting in terms of improving transparency in resource allocation, identifying full costs of governments’ activities, and engendering high quality statistics, i.e. the Government Finance Statistics (GFS) and the European System of Accounts (ESA), which are crucial for fiscal and spending decisions, have been made by international organisations [e.g. the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank], regional policy makers [e.g. the European Commission (EC)], international accounting and auditing standards setters [e.g. the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) and the EUROSTAT], and professional accounting associations and accounting firms [e.g. the Federation of European Accountants (FEE), the Chartered Institute of Public Finance & Accountancy (CIPFA), Ernst & Young and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC)], all of which are considered to be major proponents of public sector accruals (see e.g. FEE, 2007; IFAC, 2011; PWC, 2013).

Despite this support, many of these proponents have also cautioned the implementation of accrual accounting in the public sector, given its technical ambiguities and the amount of resources and expertise that the countries should make available to address them (FEE, 2007; IFAC, 2011; IMF, 2009). For instance, professional associations, standards setters and firms of auditors or accountants have expressed several reservations with regard to the adoption of accrual accounting and International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSASs) by the EU member states (European Commission, 2012). Within the academic community, the move towards accrual accounting has been a debated reform trajectory (Broadbent & Guthrie, 2008; Carlin, 2005). Whilst some academics are apparently convinced of the benefits of accrual accounting (see e.g. Anessi-Pessina & Steccolini, 2007; Ball, 2012; Bergmann, 2012; Caperchione, 2006; Chan, 2003; Likierman, 2003; Lüder & Jones, 2003), others have raised concerns over the pertinence of business-like accrual accounting in public entities, which have different objectives and contexts (see e.g. Becker, Jagalla, & Skærbæk, 2014; Carlin, 2005; Connolly & Hyndman, 2006; Ezzamel, Hyndman, Johnsen, & Lapsley, 2014; Guthrie, 1998; Mellett, 2002; Monsen, 2002). The latter group is of the view that the implementation of accrual accounting is driven more by legitimacy than efficiency reasons and that the benefits of accrual accounting are overstated.

The arguments for and against the implementation of public sector accruals – uttered by international organisations, policymakers, standards setters, professional accountants and academics – are claimed to be normative and lacking empirical evidence (Jagalla, Becker, & Weber, 2011; Lapsley et al., 2009). For example, there is apparently a gap between what is normatively expected from accrual accounting and what has been achieved in its implementation at different organisational levels in practice (Guthrie, 1998). This is evident in countries such as Australia and the UK – the early adopters of accrual accounting and budgeting – given the time and resources consumed in the implementation (Connolly & Hyndman, 2006; Guthrie, 1998; Hyndman & Connolly, 2011). Missing from the public sector accrual literature, however, are the voices of actors at the organisational level, primarily government accountants, budget officers and policy makers, who are actually involved in implementing accrual accounting. Questions that are yet to be answered in the public sector accrual literature include how such organisational actors are advancing public sector accruals reforms in their specific settings, the strategies and mechanisms they are deploying and the specific challenges that they are encountering in the implementation process.

This paper strives to fill this knowledge gap in the public sector accrual literature. We seeks to make heard the voices of accountants, budget officers, and policy makers involved in implementing various aspects of accrual accounting and budgeting in different OECD member states. This is approached through the extended version of neo-institutionaltheory, also referred to as new institutionalism (Carruthers, 1995; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), particularly the version that acknowledges the role of intra-organisational actors in the institutionalisation process. Some aspects of a framework proposed by Dillard, Rigsby, and Goodman (2004) have been adopted. This angle allows us to delineate how the public sector accrual ideas and practices cascade down through different levels, in particular the economic and political level (i.e. the OECD), the organisational-field level (i.e. OECD member states), and the organisational level (i.e. actors in different OECD member states), prior to their adoption in particular contexts.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. The ideas of new institutionalism, which provide a sensitising lens for this study, are presented in Section 2. The research method is outlined thereafter. Section 4 presents the views and experiences of OECD member states with regard to public sector accruals and the challenges they have encountered in implementing different elements of accrual accounting, budgeting and IPSASs in their specific contexts. The final section analyses the implementation of public sector accruals in the member states in the light ofthe theory, and offers some concluding remarks.

2. Theoretical framework: extended new institutionalism

Public sector accounting scholars have striven to theorise accounting changes using varied sociological approaches (see e.g. Goddard, 2010; Jacobs, 2012; Van Helden, Johnsen, & Vakkuri, 2008). For instance, several pieces of research have drawn on the ideas of actor network theory, in particular the concept of translation (see e.g. Callon, 1986; Latour, 1987) to analyse how accounting changes (see e.g. Justensen & Mouritsen, 2011) and the ways in which innovations, through a network of human and non-human allies, have taken place in the health care sector (Chua, 1995; Lowe, 2000; Preston, Cooper, & Coombs, 1992) as well as in other public sector settings (Christensen & Skærbæk, 2007, 2010; Lukka & Vinnari, 2014). The widespread adoption of accrual accounting in the public sector has nevertheless been predominantly associated with the ideas of new institutionalism (Jacobs, 2012; Modell, 2013). Many theoretical perspectives have failed to explain accounting changes withreference to external variables/environment, which have increasingly become dominant in regulating accounting practices at a global level. Implicit in neo-institutional theory (see e.g. DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1977) is the role of external organisations/institutions, for instance, the IFAC, the European Commission, and the OECD amongst others, in disseminating public sector accounting reforms (Jacobs, 2012). The extent public sector accounting literature has therefore drawn on neo-institutional theory to investigate how similar reform ideas (i.e. accrual accounting and the IPSASs) have been diffused across countries, although there are significant variations in reform outcomes, i.e. practice variations (Ahn, Jacobs, Lim, & Moon, 2014; Carpenter & Feroz, 2001; Ezzamel, Hyndman, Johnsen, Lapsley, & Pallot, 2007; Hyndman & Connolly, 2011; Oulasvirta, 2014; Pollanen & Loiselle-Lapointe, 2012).

The ideas of new institutionalism have primarily drawn on the notions of “legitimacy” and “isomorphism” (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1977). It is stated that organisations tend to conform to socially accepted norms and structures as part of their legitimacy-seeking behaviour, and in the process become isomorphic. DiMaggio and Powell (1983) mention three pressures/mechanisms contributing to organisational isomorphism, i.e. coercive, mimetic, and normative. Whilst the coercive mechanism, especially in the public sector, has been linked to state intervention and pressure from resource providers, the normative mechanism has been seen as an outcome of professionalisation (e.g. through the influence of consultants, scholars or other esteemed professionals). The mimetic mechanism is concerned with emulating the ubiquitous practices in the field which have a tag of being successful and modern. A stream of public sector literature draws on these three mechanisms to explain how the adoption of accrual accounting has become an integral element of legitimacyseeking behaviour, thereby illuminating the case of accounting choices within organisations (Adhikari, Kuruppu, & Matilal, 2013; Ball & Craig, 2010; Carpenter & Feroz, 2001; Irvine, 2008). Ensuring legitimacy has been indispensable for public sector entities, not only to avoid critical questions regarding their activities but also to portray their image as modern and rational organisations in their operating contexts. However, Hyndman and Connolly (2011:38) have differentiated between organisations/countries in terms of their concerns over legitimacy. They argue that the early adopters of accrual accounting in the public sector, i.e. New Zealand, Australia and the UK, were to a large extent motivated by technical economy efficiency gains, but that the later adopters were more concerned with legitimacy and involved in “mindless imitation fuelled by anxiety-driven pressures to conform”.

چکیده

1. مقدمه

2. چارچوب نظری: نهادینهسازیِ مبسوطِ نوین

4. بخش تجربی

4.1 پیادهسازیِ حسابداری تعهدی

4.2 اهمیت بودجهبندیِ حسابداری تعهدی

4.3 کاربردپذیریِ IPSASها

5. بحث و نتیجه

منابع

ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical framework: extended new institutionalism

3. Research setting, data collection and analysis

3.1. An overview of the annual public sector accruals symposium

3.2. Data collection

3.3. Data analysis

4. Empirical section

4.1. The implementation of accrual accounting

4.1.1. Political challenges

4.1.2. Technical challenges

4.2. Significance of accrual budgeting

4.3. The applicability of IPSASs

5. Discussion and conclusions

References