دانلود رایگان مقاله روابط پویا بین درآمدهای نفتی، مخارج دولت و رشد اقتصادی

چکیده

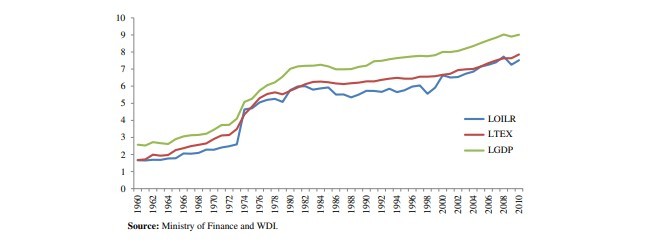

هدف از این مقاله ، به طور تجربی بررسی رابطه پویا بین درآمدهای نفتی، مخارج دولت و رشد اقتصادی در دولت سلطنتی بحرین است. درآمد نفت منبع اصلی تامین مالی مخارج دولت و واردات کالا و خدمات است. افزایش قیمت نفت در سال های اخیر هزینه های عمومی در زیرساخت های اجتماعی و اقتصادی را افزایش داده است. در این مقاله، ما بررسی می کنیم که آیا هزینه های عظیم دولت سرعت رشد اقتصادی را افزایش داده است یا نه. برای این منظور، ما از تجزیه و تحلیل هم ادغامی چند متغیره و مدل تصحیح خطا و داده ها در سالهای 1960-2010. استفاده کردیم. نتایج کلی بیان می کند که درآمدهای نفتی به عنوان منبع اصلی برای رشد و کانال اصلی در تامین مالی مخارج دولت باقی می ماند.

1. مقدمه

آیا منابع طبیعی غنی برای یک کشور نعمت یا مصیبت است ؟ این سوال برای کار علمی قابل توجه ایجاد شده است. اگرچه با کارعلمی گسترده، یک پاسخ قانع کننده ارائه نشده است. علاوه بر این، ارتباط فراوانی بین منابع طبیعی و رشد اقتصادی در میان دانشمندان مورد بحث است. این نمی تواند در میان اقتصاد دانان حل و فصل شود که فراوانی منابع طبیعی هم یک مصیبت و یا یک برکت و رحمت برای کشورهای غنی از منابع طبیعی است.

اولین قسمت از مطالعات علمی یک رابطه منفی بین وفور منابع و عملکرد ضعیف اقتصادی ایجاد می کند (آتی (1986، 1990، 1993، 1998، 2001)، بولمر توماس (1994)، گلب (1988)، لعل و مینت (1996)، رانیس (1991)، ساکس و وارنر (1995، 1997، 1999). نتایج ظاهر می شود تا از فرضیه " منابع مصیبت" حمایت کند. ساکس و وارنر (1997) یک رابطه منفی روشن بین منابع طبیعی مبتنی بر صادرات (کشاورزی، مواد معدنی و سوخت) و رشد در دوره 1970-1990 از 95 نمونه از کشورهای در حال توسعه پیدا کرد بجز دو کشور مالزی و موریس که 2٪ در هر سال رشد اقتصادی در طول سالهای 1970-1980 داشتند. به همان شیوه، آتی (2001) متوجه شد که رشد درآمد سرانه کشورهایی با منابع فقیر بین دو تا سه برابر سریع تر از کشورهای با منابع فراوان برای دوره 1960-1990 است. او اذعان می کند که فراوانی منابع محصول انتظار می رود که رشد کمتری نسبت به معادل تولید آن داشته باشد. علاوه بر این، کشورهای معدنی در میان ضعیف ترین اجراکنندگان بوده اند. این به اصطلاح " منابع مصیبت" نامیده می شود که از بسیاری اقتصاددانان برای توضیح ریشه های اصلی آن الهام گرفته شده است.

به هرحال، چنین نتیجه گیری بیان شده فوق الذکر بدون انتقاد نیست. نتایج به دوره انتخاب، به تعریف "منابع طبیعی" و به روش مورد استفاده بسیار حساس هستند. برخی از محققان برخی شک و تردید هایی در مورد استحکام این یافته ها به علت تفاوت در اندازه گیری فراوانی منابع طبیعی بیان می کند (استیجنز، 2005). شرانک (2004) توضیح می دهد که این شواهد اثبات نمی کند که منابع طبیعی فراوانی از هر نوع باعث رشد ضعیف اقتصادی می شود حتی اگر آنها در ارتباط باشند. ارتباط علت و معلولی نیست. این چیزی است که ما در هر کتابچه راهنمای کاربر اقتصاد خواندیم. راس (2003) فراتر می رود و بیان می کند که رابطه بین فراوانی منابع طبیعی و اقتصادهای ضعیف ممکن است کاملا با حذف یک متغیر سوم جعلی همراه باشد.

همانطور که در بسیاری کشورهای غنی از منابع طبیعی، رشد اقتصادی بحرین به شدت تحت تاثیر نوسانات نفت، گاز و قیمت مواد معدنی در بازارهای بین المللی قرار گرفته است. این وابستگی اقتصادی بحرین به بخش نفت خود را نشان می دهد حتی اگر آن به عنوان حداقل وابسته نفتی در مقایسه با همسایه های خود در منطقه در نظر گرفته شود. نرخ رشد بحرین به طور کلی به دنبال یک مسیر مشابه به نرخ رشد عربستان است اما به دلیل شکاف بزرگ در تولید نفت و گاز و ذخیره بین دو کشور کمتر فرار است.

بحرین یکی از اولین کشورهای خلیج فارس بود که شروع به متنوع ساختن اقتصاد کرد. در اواخر دهه 70، دولت یک گام به جلو در سیاست تنوع سازی با جذب موسسات مالی و خدمات برای راه اندازی دفاتر منطقه ای در کشور برداشت. علاوه بر این، بحرین در میان اولین کشور در شرق میانه و منطقه شمال آفریقا یک پایگاه صنعتی ایجاد کرد و آن برای سرمایه گذاران خارجی، از جمله سرمایه گذاران منطقه ای در توسعه صنعتی آن (لونی 1989) جذاب بوده است. در طول دهه گذشته، دولت اصلاحات ساختاری را تشدید کرده است تا زیرساخت های پادشاهی و همچنین رفاه شهروندان بحرینی را بهبود بخشد. بحرین به یک اقتصاد باز با تجارت آزاد و حساب سرمایه تبدیل شده است. آن نیز مرکز امور بین المللی و مکان مورد نظر برای سرمایه گزارن شده است. کشور بحرین به سرعت در حال تبدیل شدن ، به عنوان یک کشور کلیدی برای بانکداری، امور مالی اسلامی، صنعت بیمه اسلامی، حمل و نقل و ارتباطات در منطقه خلیج فارس است و مکان بسیاری از شرکت های چند ملیتی شده است . امروزه، اقتصاد بحرین به عنوان اقتصاد پویایی بی سابقه ای شناخته شده است، جمعیت به شدت در حال رشد است و پروژه ها دوبرابر شده است. هدف دولت بحرین در توسعه برنامه های این بود که وابستگی هزینه های جاری به درآمدهای نفتی، تامین مالی این هزینه ها از طریق منابع غیر نفتی را کاهش دهد.

به هرحال کاهش در فعالیت های اقتصادی بین سالهای 1990 و 2000 باعث شده است که عدم تعادل شدید مالی برای بحرین و درامد های نفتی به شدت کاهش یابد. در طول دهه گذشته، وضعیت بدتر شده است همانطورکه اقتصاد جهانی یک دوره نوسانات شدید در قیمت های نفت را تجربه می کند. در نتیجه، موقعیت مالی بحرین از کمبود جزئی در سال 2002 (0.1٪ - از تولید ناخالص داخلی) به کسری بیشتر از حدود 10٪ از تولید ناخالص داخلی در سال 2009 با توجه به کاهش درآمدهای نفتی نقل مکان کرد. درآمد کل از BD 1.04 میلیارد در سال 2000 به 2.8 میلیارد BD در سال 2008 قبل از کاهش به BD 1.7 میلیارد در سال 2009 (سازمان انفورماتیک مرکزی، 2011) افزایش یافته است. درآمدهای نفت و گاز رشدی از BD 765 میلیون در سال 2000 به 2.3 میلیارد BD در سال 2008 قبل از کاهش به BD 1.4 میلیارد در سال 2009 ثبت کردند، در حالی که درآمدهای غیر نفتی از BD 264 میلیون در سال 2000 به BD 367 میلیون در سال 2008 قبل از کاهش به BD 262 میلیون در سال 2009 (سازمان انفورماتیک مرکزی، 2011) افزایش یافت. این بدان معنی است که درآمد دولت و سیاست های مالی به طور کلی در بقای سلطنت به شدت وابسته به درآمدهای نفتی است. درآمد نفت، خون زندگی اقتصاد بحرین (حمدی و صبا، 2013 a، b) است.

صرف نظر از نوسانات درآمد نفت، دولت همیشه سطح بالایی از هزینه های جاری را حفظ کرده است. در مقابل، سرمایه و یا توسعه هزینه به نوسانات درآمدهای نفتی حساس می باشد. این مشاهدات ساده و به طور کلی نشان می دهد آسیب پذیری وضعیت مالی دولت به شوک درآمد نفت غیر منتظره وابسته است. دولت نمی تواند هزینه های فعلی خود را به راحتی در مورد بازار منفی نفت تنظیم کند. در این شرایط، زمانی که قیمت نفت کاهش می یابد، دولت قادر نیست که حجم فعالیت های خود را بلافاصله کاهش دهد، منجر به کسری بودجه قابل توجهی می شود (فرزانگان، 2011). این باعث می شود که کسری بودجه یک مسئله حیاتی برای دولت شود. پس از آن مهم است که به طور جدی تر اصلاح نظام مالیاتی بررسی شود.

با توجه به وزن نفت در کشور پادشاهی کوچک، این مقاله بر اهمیت درآمدهای نفتی در تامین نیازهای مالی دولت و بهبود رفاه خانواده بحرینی تاکید می کند. دقیقا، هدف آن بررسی روابط پویا بین درآمدهای نفتی، کل مخارج دولت و رشد اقتصادی در کشور سلطنتی بحرین است. در دانش ما، این نوع از سوال هرگز در کارهای علمی مدرن با وجود اهمیت نفت در تامین مالی اقتصاد کشورهای وابسته به نفت تجزیه و تحلیل نشده است. بنابراین این مقاله، اولین تلاش در کارعلمی برای تجزیه و تحلیل روابط کوتاه مدت و بلند مدت بین درآمدهای نفتی، مخارج دولت و رشد اقتصادی در مورد یک اقتصاد وابسته به نفت است. برای رسیدن به این هدف، ما از یک مدل اقتصاد سنجی بر اساس هم ادغامی و تکنیک های مدل تصحیح خطا برای سری داده های زمانی طولانی استفاده می کنیم که دوره زمانی آن از سال 1960 تا سال 2010 است. نتایج کلی نشان می دهد که با وجود تلاش های دولت بحرین برای تنوع بخشیدن به اقتصاد خود، درآمدهای نفتی به عنوان منبع اصلی برای رشد و کانال اصلی باقی می ماند که مخارج مالی دولت همانطورکه آنها 87.85٪ از مجموع درآمدهای دولت در سال 2011 را نشان می دهند (سازمان انفورماتیک مرکزی، 2011). بنابراین، ما دولت بحرین را تشویق می کنیم تا به سیاستهای خود بر روی استراتژی های رشد گرا موثر ادامه دهد و به اصلاحات ساختاری بیشتری برای توسعه بخش غیر نفتی انجام دهد.

بقیه مقاله به شرح زیر است: بخش 2 زمینه نظری در مورد عواقب اقتصاد کلان از نوسانات قیمت نفت، بخش 3 روش اقتصاد سنجی ،. بخش 4 نتایج در حالی که بخش 5 نتیجه گیری را ارائه می دهد .

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to empirically examine the dynamic relationships between oil revenues, government spending and economic growth in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Oil revenues are the main source of financing government expenditures and imports of good and services. Increasing oil prices in the recent years have boosted public expenditures on social and economic infrastructure. In this paper, we investigate whether the huge government spending has enhanced the pace of economic growth or not. To this end, we use a multivariate cointegration analysis and error-correction model and data for 1960–2010. Overall results suggest that oil revenues remain the principal source for growth and the main channel which finance the government spending.

1. Introduction

Is natural resource-rich a blessing or a curse for a country? This question has generated considerable academic work. Even though, with an extensive literature, a convincing answer is not provided. Furthermore, the relationship between natural resource abundance and economic growth is controversial among scholars. It could not be settled among economists that natural resource abundance is either a curse or a blessing for natural resource-rich countries.

The first body of the literature establishes a negative relationship between resource abundance and poor economic performance (Auty (1986, 1990, 1993, 1998, 2001), Bulmer-Thomas (1994), Gelb (1988), Lal and Myint (1996), Ranis (1991), Sachs and Warner (1995, 1997, 1999)). The results appear to support the “resource curse” hypothesis. Sachs and Warner (1997) find a clear negative relationship between natural resource based exports (agriculture, minerals and fuels) and growth in the period 1970–90 from a sample of 95 developing countries. Two exceptions were Malaysia and Mauritius that sustained 2% per year growth during 1970–80. In the same way, Auty (2001) found that per capita income of resource poor countries grew between two to three times faster than that of the resource-abundant countries for the period 1960–1990. He admits that crop-led resource abundance would be expected to have lower growth compared to its manufacturing equivalent. Furthermore, mineral driven countries have been among the weakest performers. This so-called “resource curse” has inspired many economists to explain its origins.

Nevertheless, such conclusions exposed above are not without criticism. The results are very sensitive to the period chosen, to the definition of “natural resources” and to the methodology used. Some scholars put forward some doubts about the robustness of these findings due to differences in the measurements of natural resources abundance (Stijns, 2005). Schrank (2004) explains that this evidence does not prove that natural resources abundance of any kind causes poor economic growth even if they are correlated. Correlation does not mean causation. This is what we read in every econometrics manual. Ross (2003) goes further and put forward that the relationship between natural resources abundance and poor economies may be completely spurious by omitting a third variable.

As in most natural resource-rich countries, Bahrain's economic growth has been strongly influenced by the volatility of oil, gas and mineral prices in international markets. This reveals Bahrain's economic dependence on its oil sector even though it is considered as the least oil dependent compared to its regional peers. Bahraini growth rates have generally followed a similar path to Saudi growth rates but have been less volatile because of huge gaps in oil and gas production and reserve between the two countries.

Bahrain became one of the first Gulf countries to start diversifying its economy. In the late 70s, the government went one step further in its diversification policy by attracting financial and service institutions to set up regional offices in the country. Moreover, Bahrain was among the first countries in the Middle East and North Africa region to build an industrial base and it has been the most attractive for foreign investors, including regional ones in its industrial development (Looney, 1989). During the past decades, the government has intensified the structural reforms to improve the infrastructure of the kingdom as well as the well being of Bahraini citizens. Bahrain has become an open-ended economy with liberalized trade and capital account. It has also become the hub of international affairs and the preferred destination for investors.1 Quickly, Bahrain emerged as a key player for banking, Islamic finance, Islamic insurance industry, transportation and communication in the Gulf region and has become home to many multinational firms. Nowadays, the economy has known an unprecedented dynamism, population has been growing drastically and projects have been multiplying. The goal of the Bahraini government in development plans was to reduce the dependence of current expenditures to oil revenues, financing these costs through non-oil sources.

Nevertheless, the slow-down in economic activity between the 1990s and 2000s has caused severe fiscal unbalances for Bahrain and oil revenues decreased drastically.2 During the last decade, the situation has worsened as the world economy has known a period of severe volatility in oil prices.3 As a result, Bahrain's fiscal position moved from a minor deficit in 2002 (−0.1% of GDP) to a greater deficit of about 10% of GDP in 2009 due to the drop in oil revenues. Total revenue increased from BD 1.04 billion in 2000 to BD 2.8 billion in 2008 before decreasing to BD 1.7 billion in 2009 (Central Informatics Organisation, 2011). Oil and gas revenues registered a growth from BD 765 million in 2000 to BD 2.3 billion in 2008 before decreasing to BD 1.4 billion in 2009, while non-oil revenues rose from BD 264 million in 2000 to BD 367 million in 2008 before going back BD 262 million in 2009 (Central Informatics Organisation, 2011). This means that the government revenues and the overall fiscal policy in the Kingdom remain hugely based on oil revenues. Oil revenues are the life blood of the Bahraini economy (Hamdi and Sbia, 2013a,b).

Regardless of oil revenue volatility, the government has always kept a high level of current expenditures. By contrast, capital or development expenditures are sensitive to fluctuation in oil revenues. These simple and general observations show the vulnerability of the government fiscal situation to unexpected oil revenue shocks. Government cannot adjust its current spending easily in the case of a negative oil market. In this condition, when oil prices go down, the government is not able to reduce the size of its activities immediately, leading to a significant budget deficit (Farzanegan, 2011). This makes budget deficits a critical issue for the government. It is then important to consider a reform of the tax system more seriously.

Given the weight of oil in the small kingdom, this paper sheds light on the importance of oil revenues in financing the government needs and improving the well-being of Bahraini households. Precisely, it aims at investigating the dynamic relationships between oil revenues, total government expenditures and economic growth in the Kingdom of Bahrain. To the best of our knowledge, this type of question has never been analyzed in modern literature despite the importance of oil in financing the economies of oil-dependent countries.4 Therefore, this paper is the first attempt in literature to analyze the short-run and long-run relationships between oil revenues, government expenditures and economic growth in the case of an oil-dependent economy. To reach this goal, we use an econometric model based on cointegration and error correction model techniques for a long time series data which covers the period from 1960 to 2010. Overall results suggest that despite the efforts of the Bahraini government to diversify its economy, oil revenues remain the principal source for growth and the main channel that finance government spending as they represent 87.85% of total government revenues in 2011 (Central Informatics Organisation, 2011). Therefore, we encourage the government of Bahraini to continue working on effective growth-oriented strategies and to undertake more structural reforms to promote non-oil sector.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a theoretical background on the macroeconomic consequences of oil price volatility. Section 3 presents the econometric methodology; Section 4 provides the results while Section 5 concludes.

چکیده

1. مقدمه

2. پیامدهای اقتصاد کلان نوسانات نفت

3. روش های اقتصاد سنجی

3.1 داده ها

3.2 روش شناسی

4. نتایج تجربی

4.1 آزمون ریشه واحد

4.2. هم ادغامی: بلند مدت و کوتاه مدت

4.3 توابع عکس العمل آنی

5. نتیجه گیری و الزامات سیاستگذاری

منابع

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Macroeconomic consequences of oil volatility

3. The econometric methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Methodology

4. Empirical results

4.1. Unit root tests

4.2. Cointegration: long-run and short-run

4.3. Impulse response functions

5. Conclusion and policy implications

References