دانلود رایگان مقاله فراغت جدی و فوتبال در دانشگاه فلوریدا

چکیده

مفهوم فراغت جدی ( استبینز، 1979، 1992) برای بررسی معانی، رسوم و رویههای مربوط به طرفداری از تیم فوتبال دانشگاه فلوریدا بهکار رفت. به عقیده ما هواداران این تیم به خوبی نمایانگر طبقه فراغت جدی در بین افرادی است که فعالیتی دلخواه را دنبال میکنند. برای انجام تحقیق، مصاحبههای عمیق رو در رو با چهار زن و شانزده مرد از بین این طرفداران انجام شد. مصاحبهها مکتوب و سپس با استفاده از شیوههای مقایسه مستمر و داده بنیاد مورد تحلیل قرار گرفت ( گلیزر و استراس، 1967؛ استراتس و کوربین، 1998 الف و ب ). مضامین برخاسته از دادهها موید شش ویژگی فراغت جدی بود که استبین به آن اشاره داشت. نتایج حاکی از آن است که هواداری از تیم فوتبال گیتر نه تنها منبعی از هویت فردی را به ارمغان میآورد، بلکه در جامعه ای با بخشبندیهای فزاینده پست مدرن، به فرد نوعی حس تعلق میبخشد.

دیباچه

در سراسر دنیا، ورزش موجب میشود توجه تمامی سطوح جامعه از شرکت کنندگان گرفته تا هواداران به رسانهها، دولتها و شرکتهای چندملیتی جلب شود. دانینگ (1999) بیان میکند در طول تاریخ و در سراسر دنیا، هیچ فعالیتی این چنین مستمر به عنوان کانون دغدغهها و علایق مشترک چنین خیلی عظیمی از انسانها وجود نداشته است" ( صفحه 3). با افزایش پیچیدگیها و بخشبندیها در جامعه مدرن ( سیمل ، 1955) و اینک پست مدرن ( دانینگ، 1999)، جامعهشناسان معتقدند جهانهای اجتماعی و فرصتهای هویت جمعی که در ذات ورزش نهفته است، به این مقوله اهمیتی فزاینده میبخشد. البته به گفته دانینگ " همانندسازی تیمهای ورزشی میتواند به افراد نوعی دارایی هویتی مهم یا احساسات جمعی داده و زمینهساز حس تعلق به چیزی را فراهم آورد که در نبود ورزش، به تجربه زیستی انزواگرایانه مبدل میشود" ( صفحه ).

طی سالیان گذشته، بسیاری از صاحبنظران به بررسی اهمیت اجتماعی ورزش در سطح خرد و زندگی هواداران و همچنین در سطح کلان جامعه پرداختهاند. در این تحقیقات موضوعاتی نظیر طرفداران ورزشی عمیقا متعهد ( مک فرسون ، 1975)، همانندسازی " انطباق مثبت " و " انطباق منفی " (چیالدینی و دیگران، 1976؛ کیمبل و کوپر ، 1992؛ لی ، 1985؛ وان و برانسکومب ، 1990)؛ سطوح همانندسازی در هواداران ( اندرسون ، 1979، وان و برانسکومب، 1993)؛ سطوح رضایت طرفداران ( مادریگال ، 1995) ؛ مشارکت هواداران ( کرستتر و کوویچ ، 1997؛ شانک و بیزلی ، 2000) و هواداری به عنوان تلاشی برای تعلق ( اندرسون و استون ، 1981؛ دانینگ، 1999) مورد مطالعه قرار گرفته است. با این حال تا کنون بیشتر تحقیقات انجام شده بر روی هواداران ورزشی در ایالات متحده بر دانشجویان به عنوان هوادار متمرکز بوده است. از سوی دیگر، لازم است جایگاه هواداری ورزشی در بافت زندگی افراد درک گردد زیرا انسانها در جریان زندگی از مراحل مختلفی عبور میکنند. وجه تمایز تحقیق پیش رو آن است که تلاش داریم به هواداران در بلندمدت توجه داشته باشیم که برخی از آنها حرفه خود در مقام هوادار را در دوران دانشجویی یا به عبارتی 50 سال قبل آغاز کردهاند.

گرچه اندیشمندان ورزشی به تحلیل ابعاد مختلفی از رفتارهای هواداری و نقش ورزش در جامعه پرداختهاند، جهان اجتماعی هواداران از دید صاحبنظران فراغت پنهان مانده است (جونز ، 2000). با توجه به اهمیت ورزش به عنوان شیوهای اصلی در گذران اوقات فراغت در ایالات متحده و سراسر جهان، این مسئله تا حدودی عجیب به نظر میرسد. فلسفه هدایتگر محققان این پژوهش آن است که فراغت حوزهای کلی مشتمل بر گونههای خاص تفریحات، ورزش و گردشگری است. به همین دلیل ما معتقدیم کاوشی عمیق در خرده فرهنگ ورزش در درک رفتارهای فراغت ضروری و قابلتوجه خواهد بود.

متخصصان حوزه فراغت جهانهای اجتماعی مختلفی را مورد مطالعه قرار دادهاند که از هواداری مجزاست، از جمله شرکتکنندگان در کلوپ امریکایی کنل ، صیادان ماهی خاردار که در مسابقات ماهیگیری شرکت میکردند، سازندگان خانههای عروسکی و پرندهنگران . نتایج نشان داد مشارکت در این فعالیتها معمولا منبعی از معنا و هویت برای افراد به همراه میآورد ( برای مثال بالدوین و ونوریس ، 1999؛ بارترام ، 2001؛ کراوچ ، 1993؛ ایروین ، 1977؛ کلرت ، 1985؛ میتل استائد ، 1995؛ اولمستد ، 1993؛ اسکات و گودبی ، 1992، 1994؛ استبینز ، 1979، 1992؛ یودر ، 1997). پرسشی که اینک به ذهن متبادر میشود آن است که آیا جهانهای اجتماعی مبتنی بر ورزش در ایالات متحده به هواداران فرصتهای مشابهی در زمینه همانندسازی و معنابخشی میدهند یا خیر؟

به نظر میرسد برای طرفداران فوتبال در دانشگه فلوریدا، گیتور بودن، منبعی مهم از معنا و هویت است که در طرز پوشش، صفاتی که در توصیف خود به کار میگیرند و بعضا رنگ ماشینهایی که میرانند یا مکانهایی که در آنها زندگی میکنند، نمودار میگردد. برخی از این افراد هزاران مایل را با همراهی تیم خود سفر میکنند تا با خانواده و دوستان خود در جاده پشت سر هم حرکت کنند . برای برخی از فارغالتحصیلان ، فوتبال حلقه پیوند میان آنها و دانشگاه پیشین آنهاست. هیچ ورزش دیگری در ایالات متحده نمیتواند چنینجو، مراسم و فرآیندهای اجتماعیسازی عمیقی را پیش از شروع مسابقات ( نظیر رانندگیهای زنجیرهای) فراهم آورد. با این حال صاحبنظران عرصه فراغت با چندین پرسش مواجهند که نیازمند بررسی است. چرا هواداران تیم فوتبال گیتور تا این حد برای پشتیبانی از تیم خود زمان و انرژی صرف میکنند؟ معانی، مناسک و رویه های مرتبط با هواداری از تیم فوتبال فلوریدا چیست؟ آیا هوادار گیتور بودن نوعی فراغت جدی محسوب میشود؟

به عقیده استبینز (1982) "تماشای بازی فوتبال" یا تماشاچی بودن به معنای فراغت جدی نبوده و خصوصیتی از فراغت غیرجدی و تفریحی محسوب میشود. برخلاف استبینز، ما معتقدیم هواداران گیتور با سطح بالایی از تعهد و همانندسازی تیمی، به خوبی نمایانگر طبقهای با فراغت جدی هستند زیرا این افراد در نسبت به فعالیتهای خود جدی و متعهدند" (استبینز، 1982، 259). به زعم ما " هواداران صرفا تماشاچیانی منفعل نیستند، بلکه عنصری اساسی در عملکرد صحیح هر نهاد ورزشی برای جامعه و افراد محسوب می شوند" ( ادواردز ، 1973، 23). بر این اساس هدف اصلی این تحقیق بررسی معانی و مناسک مرتبط با هواداری از تیم فوتبال گیتور در دانشگاه فلوریدا بود. اهداف ثانویه پژوهش حاضر نیز شامل بررسی ساخت هویت و هویت جمعی در هواداران تیم فوتبال گیتور بود. در این مقاله از مفهوم فراغت جدی ( استبینز، 1970، 1982، 1992، 2001) برای در تحلیل دادهها استفاده شد. همچنین این پرسش مطرح شد که آیا هواداری ورزشی میتواند سازنده نوعی فراغت جدی با مسیر شغلی، خصلتی منحصر به فرد و نظایر این برای هواداران تیم مذکور باشد یا خیر. تیم پژوهش مشتمل بر اساتید و دانشجویان دانشگاه بود که در سطوح مختلف در انجمنهای اجتماعی دانشگاه فلوریدا با محوریت فوتبال عضویت داشتند. برخی از این اعضا دانشجویان مقطع کارشناسی در دانشگاه بوده و هواداران دو پرو پا قرص گیتور محسوب میشدند در حالیکه برخی دیگر به تازگی به این گروه پیوسته و جایی در میانه طیف، با تردید نظارهگر وقایع بودند.

پیشینه تحقیق

مفهوم فراغت جدی برآمده از آثار رابرت استبینز (1979؛ 1982؛1992 ؛ 2001) است. وی با تحقیقات گسترده قومشناسی در میان موسیقیدانان، ستارهشناسان، جادوگران، بازیگران طنز ، بازیکنان بیسبال و بسیاری قشرهای دیگر به نظریهای در این خصوص دست یافت. از دید او فراغت جدی شامل تعقیب نظامیافته فعالیتی مهم و جالب توسط فردی غیرحرفهای یا داوطلب به منظور مشارکت در یافتن نوعی حرفه است که در آن بتوان به حد کفایت دانش و مهارتهای مشخصی را کسب و ابراز کرد (استبینز، 1992 ، 3). وی در تحقیق خود چنین تصور کرد که سه نوع مشارکت در فراغت جدی وجود دارد، غیرحرفهایها، صاحبان سرگرمی و داوطلبان شغلی. استبینز (1992) عنوان میکند در بهترین حالت ، فراغت جدی را میتوان به عنوان کیفیتی دوسویه مشتمل بر فراغت تفریحی یا غیرجدی و نقطه مقابل آن در نظر گرفت. وی فراغت تفریحی را چنین تعریف میکند " فعالیت لذتبخشی آنی، دارای پاداش درونی با عمری نسبتا کوتاه که به هیچ آموزش خاصی برای بهرهمندی از آن نیاز ندارد" ( استبینز، 1997، 18) یا " انجام طبیعی امور " ( استبینز، 2001، 58). وی فعالیتهایی نظیر سوار شدن بر چرخ و فلک، تماشای تلویزیون یا تماشای مسابقه فوتبال (استبینز، 1982؛1992) را نمونههایی از فراغت تفریحی میداند. انجام چنین گونههایی منفعلی از تفریحات به حداقل میزان تحلیل یا به تمرکز بر محتوا نیاز دارد و " از فعالیت مذکور صرفا به خاطر خود فعالیت و نه میل باطنی یا اجبار به کاوش در آن به هر شکل لذت برده میشود". (استبینز، 2001، 60). هنگامی که چنین تفریحی از حالت منفعل به فعال تغییر یافته و به بیان دیگر مشارکت در آن نیازمند سطح مشخصی از مهارت، دانش یا تجربه است، میتوان مفهوم آن را در قالب سرگرمی یا فعالیتی غیرحرفهای تبیین کرد ( استبینز ، 1997؛ 20-19).

به همین ترتیب، فراغت جدی برای غیرحرفهایها، صاحبان سرگرمی و داوطلبان شغلی با شش ویژگی منحصر به فرد از فراغت غیرجدی یا تفریحی متمایز میشود. نخست آنکه شرکتکنندگان در فراغت جدی گاهی باید دوران سختی را پشت سر گذارند. گرچه مشارکت در این فعالیتها ممکن است نیازمند غلبه بر دشواریهایی باشد، کماکان خود فعالیت حس مطلوبی از سلامت را به افراد میبخشد. همچنین شرکتکنندگان موظف به بسط مشاغل در حوزه فراغت موردنظر خود هستند که مشتمل بر مراحل مختلف پیشرفت، تغییر و دستاوردهاست. دیگر آنکه در چنین مشاغلی ، تلاش مضاعف فردی در جهت کسب مهارت، آموزش و دانش ضروری است و مبین تجربه طولانی در نقش موردنظر می باشد” ( استبینز، 1982، 256). به علاوه شامل هشت مزیت ماندگار برای شرکتکنندگان است که شامل خودشکوفایی، غنای شخصی، خودابرازی، تجدید خویش، حس موفقیت، بهبود تصور از خود، احساس تعلق و تعامل اجتماعی ، محصولات ماندگار فیزیکی به عنوان ماحصل شرکت در این فعالیتها و لذت محض است ( استبینز، 1992). پنجم آنکه شرکتکنندگان به نوعی منش منحصر به فرد دست مییابند که در بطن آن جهان اجتماعی متمایزی وجود دارد ( اونروه، 1980) . چنین جهانی هنجارها، ارزشها و باورها خرده فرهنگی خود را داراست (استبینز، 1992). در نهایت مشارکتکنندگان در فراغت جدی معمولا با این فعالیتها همذات پنداری بالایی داشته و " با افتخار، هیجان و به دفعات در خصوص آنها صحبت میکنند" ( استبینز، 1992، 7).

Abstract

The concept of serious leisure (Stebbins, 1979; 1992) was used to examine the meanings, rituals, and practices associated with being a University of Florida Football fan. We contend that Gator football fans tvpifv the serious leisure cat egory of the hobbyist. Face to face in-depth inte1 were conducted with four female and sixteen male fans. The transcribed interviews were analvzed using constant comparison and grounded theory methods (Glaser & Str uss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998 a & b). Themes emerging from the data con firmed Stebbins' six characteristics of serious leisure. The results suggest that being a Gator football fan provides both a source of identity for the fan as an individual and a sense of belonging in an increasingly fragmented postmodern society.

Introduction

Around the world, sport garners attention at all levels of society from participants and fans to the media, governments, and multi-national corpo rations. Dunning ( 1999) argued, "no activities have ever served so regularly as foci of simultaneous common interest and concern to so many people all over the world" (p. 3). With the growing complexity and fragmentation of modern (Simmel, 1955), and now post-modern society (Dunning, 1999), so ciologists have postulated that the social worlds and opportunities for col lective identity inherent in sport raise it to a higher level of social impor tance. Indeed, Dunning suggested, "identification with a sports team can provide people with an important identity-prop, a source of 'we-feelings' and a sense of belonging in what would otherwise be an isolated existence" (p. 6).

Over the years, many scholars have examined the social importance of sport both at the micro level in the lives of fans and at the macro level of society. These studies have focused on such topics as the deeply committed sports fan (McPherson, 1975); team identification, "basking-in-reflected glory" (BIRGing) and "cutting-off-reflected-failure" (CORFing) (Cialdini, et al., 1976; Kimble & Cooper, 1992; Lee, 1985; Wann & Branscombe, 1990); levels of fan identification (Anderson, 1979; Wann & Branscombe, 1993); levels of fan satisfaction (Madrigal, 1995); fan involvement (Kerstetter & Kov ich, 1997; Shank & Beasley, 2000); and fandom as a search for community (Anderson & Stone, 1981; Dunning, 1999). To date however, most studies of sport fans in the US have concentrated on students as fans. There is a need to understand the place of sport fandom within the context of individual's lives as they transition through the various phases of the life course. Our study is unique in that we focus on long-term fans, some of who started their careers as a fan during their student days over 50 years ago.

While sport scholars have analyzed various aspects of fan-related behav iors and the role of sport in society, the social world of the fan has received scant attention from leisure scholars Uones, 2000). This is curious given that sport is a major form of leisure in the US and around the world. Our guiding philosophy is that leisure is the overall domain under which special forms of leisure, sport and tourism reside. As such, we contend that an in-depth study of a sport subculture is both warranted and significant to our under standing of leisure behavior.

Leisure scholars have examined various non-fan-related social worlds, such as American Kennel Club participants, tournament bass fishers, doll house builders, and bird watchers, and found that participation in them frequently provides a central source of meaning and identity for its members (e.g., Baldwin & Norris, 1999; Bartram, 2001; Crouch, 1993; Irwin, 1977; Kellert, 1985; Mittelstaedt, 1995; Olmsted, 1993; Scott & Godbey, 1992; 1994; Stebbins, 1979; 1992; Yoder, 1997). The question posed is do sport based social worlds in the US provide fans with similar opportunities for identifi cation and meaning?

For fans of the University of Florida football team, being a Gator appears to be a central source of meaning and identity as evident in the clothes they wear, the adjectives they use to describe themselves, and in some cases the color of the car they drive or the place they live. Some travel hundreds of miles to follow their team, to tailgate with their family and friends, and for some who are alumni of the University, football provides a link with their alma mater. No other sport in the L'.S. seems to engender the same pre game socializing (tailgating), rituals, and atmosphere as football. As leisure scholars, several questions present themselves for investigation. Why do Ga tor football fans devote so much time and effort to following their team? V\-bat are the meanings, rituals, and practices associated with being a Uni versity of Florida football fan? Is being a Gator football fan a type of serious leisure?

According to Stebbins (1982), "sitting at a football game" (p. 253) or spectating does not constitute serious leisure, but is characteristic of unser ious or casual leisure. Contrary to Stebbins, we contend Gator football fans, with high levels of commitment and team identification, typify the serious leisure category of the hobbyist, those individuals who "are serious about and committed to their endeavors" (Stebbins, 1982, p. 259). It is our con tention that "the fan is not merely a passive spectator. He (sic) is.... a vital component in the proper functioning of the institution of sport, for both society and for individuals" (Edwards, 1973, p. 23). The primary purpose of our paper was to examine the meanings and rituals associated v.'ith being a University of Florida Gator football fan. Secondary purposes were to examine the construction of identity and collective identity around being a Gator football fan. This study used Stebbins' (1979; 1982; 1992; 2001) concept of serious leisure to guide the data analysis and asked the question can sports fandom constitute a type of serious leisure with a career path, a unique ethos, and the like for Gator football fans? The research team consisted of faculty and students from the university who are members of the social world per taining to CF football to different degrees. Some of the research team were undergraduate students at UF and are avid Gator fans while others are rel atively new to Gator football and stand on the periphery of the social world and watch with incredulity.

Background to the Study

The concept of serious leisure emerged from the work of Robert Steb bins (1979; 1982; 1992; 2001). Stebbins developed a theory of serious leisure through extensive ethnographic research of musicians, astronomers, magi cians, stand-up comics, and baseball players among others. He defined seri ous leisure as "the systematic pursuit of an amateur, hobbyist, or volunteer activity that is sufficiently substantial and interesting for the participant to find a career there in the acquisition and expression of its special skills and knowledge" (Stebbins, 1992, p. 3). From this research he contended there are three categories of participation in serious leisure: amateurs, hobbyists, and career volunteers. Stebbins ( 1992) suggested that serious leisure is most effectively examined as a dichotomous quality of unserious or causal leisure as its opposite. He defined casual leisure as "immediately, intrinsically re warding, relatively short lived pleasurable activity requiring little or no special training to crtjoy it" (Stebbins, 1997, p. 18) or "doing what comes naturally" (Stebbins, 2001, p. 58). He proposed activities such as riding a roller coaster, watching television, or sitting at a football game (Stebbins, 1982; 1992) ex emplify forms of casual leisure. These forms of passive entertainment require "only minimal analysis of or need to concentrate on its contents" and the activity is "enjoyed for its own sake quite apart from any desire or obligation to study it in some way" (Stebbins, 2001, p. 60). When this entertainment evolves from passive to active, that is, participation requires a certain level of skill, knowledge or experience, it is then more accurately conceptualized as a hobby or amateur activity (Stebbins, 1997, pp. 19-20).

Serious leisure for amateurs, hobbyists, and career volunteers is further differentiated from unserious or casual leisure as it is characterized by six unique qualities. First, serious leisure participant5 must occasionally persevere through adversity. Even though participation in the activity may require individuals to conquer moments of difficulty, the activity still provides par ticipants with a positive sense of well-being. Second, participants develop careers in their chosen leisure pursuit that involve stages of development, transition, and various achievements. Third, careers in serious leisure require substantial personal effort to attain skills, training, knowledge, and exemplify "long experience in a role" (Stebbins, 1982, p. 256). Fourth, serious leisure provides eight durable benefits for the participant such as self actualization, self enrichment, self expression, renewal of self, feelings of accomplishment, enhancement of self-image, sense of belongingness and social interaction, lasting physical products as a result of participation, and pure fun (Stebbins, 1992). Fifth, participant5 develop a unique ethos, a central component of which is a distinct social world (Unruh, 1980), with its own subcultural norms, values, and beliefs (Stebbins, 1992). Sixth, serious leisure participants tend to identify strongly with their activity and "they are inclined to speak proudly, excitedly and frequently about them" (Stebbins, 1992, p. 7).

چکیده

دیباچه

پیشینه تحقیق

یافتهها

سختکوشی

مشاغل بلندمدت

تلاشهای قابلتوجه شخصی

مزایای بلندمدت فردی

منش منحصربه فرد

همانندسازی

بحث

Abstract

Introduction

Background to the Study

Methods

Study Site

Data Collection

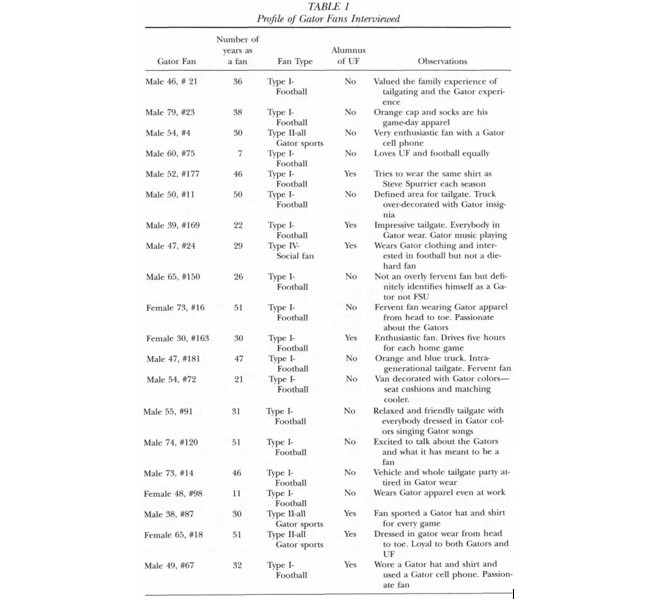

Study Particitants

Findings

Perseuerance

Long Term Careers

Significant Personal Effort

Durable Self Benefits

Unique Ethos

Identification

Discussion

References