دانلود رایگان مقاله نقشه مسیر نشخوار فکری

چکیده

نشخوار فکری به طور گستردهای مورد مطالعه قرار گرفته است و مولفه مهمی در مطالعه آسیبپذیریهای شناختی در برابر افسردگی محسوب میشود. با این حال، نشخوار فکری، معانی متفاوتی در زمینه نظریههای مختلف دارد و به طور یکپارچهای تعریف و اندازهگیری نشده است. هدف این مقاله، بررسی مدلهای نشخوار فکری و همچنین روشهای مختلف ارزیابی آن است. مدلها با توجه به چند بُعد مهم نشخوار فکری مقایسه میشوند. دستورالعملهایی برای انتخاب مدل و اندازهگیری نشخوار فکری ارائه شده و پیشنهاداتی نیز برای مفهومسازی آن فراهم میشوند. در نهایت، جهات آینده برای مطالعه پدیده نشخوار فکری بیان میشوند. امید آن میرود که این مقاله، راهنمای مفیدی برای افراد علاقمند به مطالعه ساختار چندبعدی نشخوار فکری باشد.

1. پیشگفتار

در طول دو دهه گذشته، نشخوار فکری به عنوان ساختار مهمی در شناخت پیشرفت و پایداری روحیه افسردگی تکامل یافته است. صدها مقاله به بررسی مباحث مربوط به نشخوار فکری پرداختهاند و شواهد سازگاری در مورد نقش فرایندهای تفکر اندیشناک در افسردگی ظاهر شدهاند. اگرچه تحقیقات انجام شده در پشتیبانی از نشخوار فکری، قوی هستند، هیچ گونه تعریف یکپارچهای از نشخوار فکری یا روش استانداردی برای اندازهگیری آن وحود ندارد. علاوهبراین، هنوز مشخص نیست که نحوه ارتباط نشخوار فکری با سایر ساختارهای مشابه، مانند خود-آگاهی خصوصی، مقابله احساسی، نگرانی، یا به طور کلیتر فرایندهای تفکر تکراری چگونه است. با توجه به نقش مهم نشخوار فکری در تحقیقات افسردگی، هدف این مقاله، فراهم ساختن مرور جامعی از تعاریف مختلف نشخوار فکری و ارزیابی معیارهای فعلی نشخوار فکری است. مدلهای مختلف نشخوار فکری با توجه به چند بعد مهم مقایسه میشوند و ارتباط نشخوار فکری با سایر ساختارهای مشابه مورد بررسی قرار میگیرد. امید آن میرود که خلاصه جامعی از نشخوار فکری و ساختارهای مربوطه، محققان آینده را قادر به شناسایی دقیق و شفافسازی تعریف و ارزیابی خود از این ساختار سازد و به موجب آن، کاربرد نشخوار فکری در شناخت افسردگی و سایر پیامدهای سلامت روان افزایش یابد.

2. مدلهای نشخوار فکری

مدلهای مختلفی از نشخوار فکری ارائه شدهاند. جدول ۱ نشان میدهد که این مدلها چگونه نشخوار فکری را تعریف میکنند، معیار مناسب با توجه به تعریف این ساختار را شناسایی میکند، و به طور مختصر یافتههای مربوط به مدل را خلاصه میسازد.

پربارترین نظریه نشخوار فکری، نظریه سبکهای واکنش (RST) نولن هوکسما (۱۹۹۱) است (جدول ۱). در RST، نشخوار فکری متشکل از تفکر تکراری درباره دلایل، پیامدها، و علایم تاثیر منفی فرد است. اگرچه این تعریفی با بیشترین کاربرد و پشتیبانی تجربی از نشخوار فکری است، برخی از جنبههای نظریه، مانند مولفه حواسپرتی، پشتیبانی ضد و نقیضی را دریافت کردهاند (باتلر و نولن-هوکسما، ۱۹۹۴؛ نولن-هوکسما و مورو، ۱۹۹۱). علاوهبراین، پرسشنامه سبکهای واکنش (RSQ)، به دلیل اشتراک خود با پرسشنامه افسردگی بک (بک، راش، شاو و امری، ۱۹۷۱) ، اشتراک با نگرانی، و اشتراک با شکلهای مثبت تفکر تکراری مانند تفکر بازتابی مورد انتقال قرار گرفته است. RST همچنین نحوه تطبیق نشخوار فکری در سایر فرایندهای بیولوژیکی و شناختی، مانند توجه یا باورهای متا-شناختی را مورد بررسی قرار نمیدهد.

یکی از مدلهای مربوطه، مفهومسازی «نشخوار فکری در غمگینی » است، که نشخوار فکری را به عنوان تفکر تکراری درباره غمگین بودن و شرایط مربوط به غمگین بودن فرد تعریف میکند (کانوی، کسانک، هلم و بلیک، ۲۰۰۰؛ جدول ۱). سودمندی این مدل بدین دلیل است که معیار نشخوار فکری، ممسک و خود-کفا بوده و به ویژه غمگین بودن را پیشبینی میکند. با این حال، مقیاس «نشخوار فکری در غمگینی» به طور گستردهای مورد استفاده قرار نگرفته است؛ بنابراین روشن نیست که این مقیاس در مشخص کردن نشخوار فکری در واکنش به غمگین بودن چقدر کارایی دارد و آیا در پیشبینی افسردگی یا سایر مشکلات آسیبشناختی مفید است.

مدل استرس-واکنشی نشخوار فکری ممکن است الحاق مفیدی به RST باشد که در آن، نشخوار فکری (در استنباطهای منفی مربوط به رویداد) پس از تجربه رویدادی تنشزا رخ میدهد (الوی و همکاران، ۲۰۰۰؛ جدول ۱). یکی از مزایای این مدل این است که بسیار شبیه به RST است اما ممکن است قبل از حضور تاثیر منفی، پدیده نشخوار فکری را نمایش دهد. یکی از محدودیتهای بالقوه این مدل این است که ادعا میکند که محتوای نشخوار فکری متشکل از افکار مربوط به عامل استرسزا است و ممکن است سایر موضوعات مهم نشخوار فکری، مانند خاطرات از سایر عوامل استرسزا یا افکار خود-نکوهی نامرتبط با عامل استرسزا را نشان ندهد.

نشخوار فکری پس از رویداد، مدل دیگری است که از تحقیقات فوبیای اجتماعی به دست آمده است و ادعا میکند که نشخوار فکری، در واکنش به تعاملات اجتماعی اتفاق میافتد (جدول ۱). اگرچه پردازش پس از رویداد به شناخت فرایندهای شناختی در اضطراب اجتماعی کمک میکند، مشخص نیست که آیا این مدل مخصوص فوبیای اجتماعی است یا ممکن است به ارزیابی برخی از اشتراکات در فرایندهای فکری با مشخصه اضطراب و افسردگی کمک کند. علاوهبراین، معیارهای پردازش پس از رویداد نیاز به آزمایشهای پیوسته برای تعیین کاربرد مربوطه خود در ارزیابی این ساختار دارند.

نظریه پیشرفت هدف (مارتین، تسر و مک ایتوش، ۱۹۹۳؛ جدول ۱) ، روش منحصر به فردی را برای در نظر گرفتن نخشوار فکری نه تنها به عنوان واکنشی به یک حالت خلق و خو به طور فینفسه بلکه همچنین به عنوان واکنشی به شکست در پیشرفت رضایتبخش در جهت هدف ارائه میدهد. اگرچه این نظریه ادعا میکند که نشخوار فکری و افسردگی، هر دو توسط تجربه شکست هدایت میشوند، مطالعات، حضور پایدار نشخوار فکری در غیاب شکست اخیر یا ادراک شده را مستند کردهاند (نولن-هوکسما و مورو، ۱۹۹۱؛ اسپاسوجویک، و آلوی، ۲۰۰۱). علاوهبراین، معیار نشخوار فکری در این مدل (پرسشنامه نشخوار فکری اسکات مک اینتوش، SMRI)، بر چند جنبه از نشخوار فکری، از جمله شناخت، متا-شناخت درباره نشخوار فکری (منجر به حواسپرتی یا استرس میشود)، و انگیزه تاکید دارد. بدین ترتیب، نشخوار فکری در این مدل به عنوان فرایندی وسیع و چند-بعدی شامل شناختها و همچنین تمایلات به عمل تعبیر میشود.

نظریه عملکرد اجرایی خود-تنظیمی (S-REF) از نشخوار فکری (جدول ۱)، چشمانداز وسیعتری را ارائه میدهد که در زمینه بزرگتری از مدل S-REF اختلال هیجانی، شامل توجه، تنظیم شناخت، باورهای درباره راهکارهای تنظیم هیجان، و تعاملات بین سطوح مختلف پردازش شناختی گنجانده شده است (ولز و متیوس، ۱۹۹۴، ۱۹۹۶). این مدل، باورهای متاشناختی را در مفهومسازی خود از نشخوار فکری ادغام میکند و ممکن است نقش مهمی در توسعه نشخوار فکری به عنوان سبک واکنشی پایدار داشته باشد. یکی از مشکلات بالقوه این مدل، اشتراک آن با بسیاری از ساختارهای دیگر (به عنوان مثال، نگرانی، افکار مزاحم، مقابله) است. علاوهبراین، نشخوار فکری به عنوان زیرمجموعهای از نگرانی در نظر گرفته میشود؛ با این حال، نشان داده شده است که نشخوار فکری، به شیوههای مهمی که تمایز آن از نگرانی را استدلال میکنند متفاوت از نگرانی است (برای جزئیات بیشتر، بخش مربوط به نگرانی را ببینید). مدل S-REF همچنین ادعا میکند که نشخوار فکری، ساختاری چند بعدی است و بنابراین، برای نمایش نشخوار فکری نیاز به معیارهای زیادی است (برای شرحهای مختصری از معیارها جدول ۱ را ببینید).

Abstract

Rumination has been widely studied and is a crucial component in the study of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression. However, rumination means different things in the context of different theories, and has not been uniformly defined or measured. This article aims to review models of rumination, as well as the various ways in which it is assessed. The models are compared and contrasted with respect to several important dimensions of rumination. Guidelines to consider in the selection of a model and measure of rumination are presented, and suggestions for the conceptualization of rumination are offered. In addition, rumination's relation to other similar constructs is evaluated. Finally, future directions for the study of ruminative phenomena are presented. It is hoped that this article will be a useful guide to those interested in studying the multifaceted construct of rumination.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, rumination has evolved as a critical construct in understanding the development and persistence of depressed mood. Hundreds of articles have addressed rumination related topics, and consistent evidence for the role of ruminative thought processes in depression has emerged. Although the literature supporting rumination is robust, there is no unified definition of rumination or standard way of measuring it. In addition, it remains unclear how rumination relates to other similar constructs, such as private self-consciousness, emotion focused coping, worry, or repetitive thought processes more generally. Given the important role rumination has played in depression research, the goal of this article is to provide a comprehensive review of the varying definitions of rumination and an evaluation of current measures of rumination. The various models of rumination are compared and contrasted with respect to several important dimensions and the relationship of rumination to other similar constructs is explored. It is hoped that a comprehensive summary of rumination and related constructs will enable future researchers to more accurately identify and clarify their definition and measurement of the construct, and thereby enhance rumination's utility in understanding depression and other mental health outcomes.

2. Models of rumination

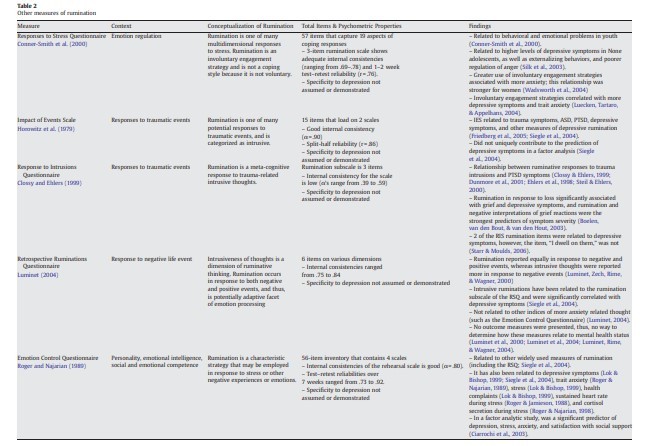

Several models of rumination have been presented. Table 1 clarifies how these models define rumination, identifies the measure that is appropriate given the construal of the construct, and briefly summarizes findings related to the model.

The most prolific theory of rumination is Nolen-Hoeksema's (1991) Response Styles Theory (RST, Table 1). In RST, rumination consists of repetitively thinking about the causes, consequences, and symptoms of one's negative affect. Although this is the most widely used and empirically supported conceptualization of rumination, some aspects of the theory, such as the distraction component, have received mixed support (Butler & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). In addition, the Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ) has been criticized for its overlap with the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), its overlap with worry, and its overlap with positive forms of repetitive thought such as reflection. The RST also does not address how rumination fits in with other biological or cognitive processes like attention or metacognitive beliefs.

A related model is the Rumination on Sadness conceptualization which defines rumination as repetitive thinking about sadness, and circumstances related to one's sadness (Conway, Csank, Holm, & Blake, 2000; Table 1). This model is useful because the measure of rumination is parsimonious and self-contained, and it specifically predicts sadness. However, the Rumination on Sadness Scale has not been widely used; therefore, it is not clear how well it specifies rumination just in response to sadness, and whether or not it is useful in the prediction of depression or other psychopathology.

The Stress-Reactive model of rumination may be a useful adjunct to RST in that rumination (on negative, event-related, inferences) occurs after the experience of a stressful event (Alloy et al., 2000; Table 1). One advantage to this model is that it is highly similar to RST, but may capture ruminative phenomena before the presence of negative affect. One potential limitation of this model is that it proposes that ruminative content consists of thoughts related to the stressor, and may not capture other important ruminative themes such as memories of other stressors, or self-deprecating thoughts not related to the stressor.

Post-event rumination is another model that arose from the Social Phobia literature and proposes that rumination arises in response to social interactions (Table 1). Although post-event processing contributes to the understanding of cognitive processes in social anxiety, it is unclear if it is specific to social phobia, or if it may help assess some of the overlap in thought processes characteristic of both anxiety and depression. Further, the measures of post-event processing require continued testing to determine their relative utility in assessing this construct.

The Goal Progress Theory (Martin, Tesser, & McIntosh, 1993; Table 1) offers a unique way of viewing rumination, not as a reaction to a mood state per se, but as a response to failure to progress satisfactorily towards a goal. Although the theory proposes that rumination and depression are both driven by the failure experience, studies have demonstrated the stable presence of rumination in the absence of current or perceived failure (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991; Spasojevic & Alloy, 2001). In addition, the measure of rumination in this model (Scott McIntosh Rumination Inventory, SMRI) taps several aspects of rumination including cognition, meta-cognitions about rumination (is it distracting or distressing), and motivation. In this way, rumination in this model is construed as a broad and multifaceted process including both cognitions and action tendencies.

The Self-Regulatory Executive Function (S-REF) theory of rumination (Table 1) offers a broader view, embedded in a larger context of the S-REF model of emotional disorder, which includes attention, cognition regulation, beliefs about emotion regulation strategies, and interactions between various levels of cognitive processing (Wells & Matthews, 1994, 1996). The model integrates metacognitive beliefs into its conceptualization of rumination, which may play a large role in the development of rumination as a stable response style. One potential problem of this model is that it overlaps with many other constructs (e.g., worry, intrusive thoughts, coping). In addition, rumination is viewed as a subset of worry; however, rumination has been shown to differ from worry in important ways that argue for its distinction from worry (see the section on worry for more details). The S-REF model also proposes that rumination is a multi-faceted construct, and, thus, many measures are required to capture rumination (see Table 1 for brief descriptions of measures).

چکیده

1. پیشگفتار

2. مدلهای نشخوار فکری

3. معیارهای نشخوار فکری

3.1. تحلیلهای عاملی نشخوار فکری

3.1.1. ابعاد مهمی که نسخوار فکری را مشخصهبندی میکنند

3.1.1.1. پایداری نشخوار فکری

3.1.1.2. عامل محرک برای آغاز چرخه نشخوار فکری

3.1.1.3. محتوای تفکر نشخوار فکری

3.1.1.4. ویژگی (ویژه بودن) نشخوار فکری در افسردگی

3.1.1.5. فعل و انفعال با متاشاختها

منابع

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Models of rumination

3. Measures of rumination

3.1. Factor analyses of rumination

3.1.1. Important dimensions that characterize rumination

3.1.1.1. Stability of rumination

3.1.1.2. Trigger for initiation of the ruminative cycle

3.1.1.3. Content of ruminative thought

3.1.1.4. Specificity of rumination to depression

3.1.1.5. Interplay with meta-cognitions

References