دانلود رایگان مقاله مسیریابی جغرافیایی چندگانه قابل اعتماد در شبکه های خودرویی ad-hoc

چکیده

شبکههای خودرویی ad-hoc (VANETها) تعداد زیادی از کاربردهای بالقوه جدید بدون تکیه بر زیرساختهای قابل توجه ارائه میکنند. بسیاری از این برنامهها از چند هاپ از اطلاعات بهرهمند هستند، در نتیجه نیاز به یک پروتکل مسیریابی دارند. ویژگیهای منحصربهفرد VANETها (مانند تحرک بالا و نیاز به نشان دادن جغرافیایی) بسیاری از پروتکلهای موقت مسیریابی نامناسب را ارئه میکنند. همچنین، برخی از کاربردهای پایانبهپایان نیازهای QoS دارند. در این مقاله یک پروتکل جدید مسیریابی multicast بهطورخاص برای VANETها پیشنهاد و طراحی شده است. هدف آن ارائه یک سرویس مسیریابی برای یک پروتکل انتقال قابل اعتماد است. که عملکرد آن را با استفاده از شبکه واقعگرایانه و مدل ترافیک ارزیابی کردیم. بنابراین نشان داده شده است که پیادهسازی یک پروتکل مسیریابی multicast قابل اعتماد برای VANETها ممکن است.

1. معرفی

برای سالها بسیاری از پروژههای تحقیقاتی در مورد مسائل درون خودرو سیستمهای ارتباطی متمرکز شده است(IVC) [1] [2] [3]. هدف از این پروژهها ایجاد "خودرو بهطورکامل متصل" است. با اجازه دادن به وسایل نقلیه جهت برقراری ارتباط با هر یک از ایستگاههای دیگر و با ایستگاه پایه در امتداد جاده، از حوادث میتوان اجتناب کرد و اطلاعات ترافیک می تواند در دسترس راننده باشد. البته، درنهایت، چشمانداز داشتن خودرویی با قابلیت دسترسی به اینترنت است. چند سال پیش VANET (شبکههای خودرویی Ad-hoc) که ترکیبی از شبکه همراه ad-hoc (MANET ها) و سیستم IVC بود معرفی شد.

شبکههای خودرویی ad-hoc (VANETها) کاهش تعداد مرگ و میر در ترافیک و بهبود آسایش سفر، برای مثال، افزایش هماهنگی بین خودرو را پیشبینی میکردند. قابل درک است که، شایعترین برنامههای کاربردی مربوط به امنیت عمومی و هماهنگی ترافیک است. برخورد سیستمهای اخطار و platooning خودرو دو برنامهی کاربردی است که پروژهها بر روی آنها کار میکنند. همچنین، برنامههای کاربردی مدیریت ترافیک، پشتیبانی از اطلاعات مسافر و برنامههای کاربردی مختلف پتانسیل این را دارند که سفر را (بطور قابل توجهی) کارآمدتر، راحت و لذتبخش کنند.

اکثر برنامههای کاربردی VANET نیاز دارند که دادهها در یک مد چند هاپ، منتقل شوند، و این نیاز به یک پروتکل مسیریابی دارد. در بسیاری از جنبهها، یک VANET میتواند بهعنوان یک MANET در نظر گرفته شود. بااینحال، طبیعت ذاتی یک VANET سه محدودیت زیر را برای یک پروتکل مسیریابی تحمیل میکند:

1. لینک کوتاه مدت

2. فقدان پیکربندی شبکه جهانی

3. عدم آگاهی از همسایگان یک گره

مورد اول با توجه به تحرک وسایل نقلیه است. مطالعات نشان دادهاند که طول عمر یک لینک بین دو گره در یک VANET در محدودهی ثانیه [4] است. شبیه به یک MANET، هیچ هماهنگکنندهی مرکزی را نمیتوان در یک VANET یافت. درنهایت، اگرچه یک پروتکل سلام (در OSPF) میتواند برای کشف همسایههای یک گره استفاده شود، بنابراین ممکن است راهحل گران قیمت و دشواری باشد. پروتکل مسیریابی باید همسایهها را در مواقع مورد نیاز کشف کند. بنابراین ترجیحا پروتکل مسیریابی برای طیف گستردهای از برنامهها و سناریوهای ترافیکی کار میکند. چند مقاله راهحلی برای برنامههای کاربردی خاص VANET پیشنهاد کردهاند [5] [6] [7]. برخی از برنامههای VANET نیاز به مسیریابی تک پخشی دارند. برای مثال، پیشبینی برنامههای کاربردی، بهعنوان مثال در بازیها و انتقال فایل، به احتمال زیاد نیاز به مسیریابی تکپخشی با آدرس ثابت دارند. بسیاری از مقالات، پروتکل تکپخشی را برای VANETها پیشنهاد کردهاند. برخی از مقالات نشان میدهند که VANETها باید از پروتکل تکپخشی موجود برای MANETها استفاده کنند، بهعنوان مثال AODV [8] [9] و یا پروتکلهای مبتنی بر خوشه [10] [11]. مقالات دیگر پروتکلهای جدید تکپخشی برای VANETها پیشنهاد میکنند [12] [13]. بااینحال، بسیاری از برنامههای کاربردی نیاز به انجام Multicast VANET مبتنی بر موقعیت دارند (بهعنوانمثال، انتشار اطلاعات در ترافیک به وسایل نقلیه نزدیک به موقعیت فعلی از منبع). مسابقه طبیعی برای این نوع از پروتکل مسیریابی geocasting است [6] [14] که پیامها را بهجلو و بهتمام گرهها در یک منطقه از ارتباط (ZOR) ارسال میکند. مفهوم geocast برای VANETها از آغاز دهه 1990 [15] مورد مطالعه قرار گرفته است. در [16] یک پروتکل geocasting برای VANETها توصیف شده است. در این روش یک گره یک پیام را پس از یک تاخیر که بستگی به فاصله از آخرین فرستنده دارد ارسال میکند. انواع دیگری از این پروتکل در [17] [18] ارائه شده است.

مشکل اصلی پروتکلهای geocasting مبتنی بر جاری شدن این است که مکانیسم جاری شدن معمولا براساس پخش است، و در نتیجه، بهترین تلاش است. اما، برخی از برنامهها نیاز به انتقال چندپخشی پایان به پایان QoS دارند. پروتکلهای geocast مبتنی بر Flooding برای این نوع از برنامههای کاربردی در نظر گرفته نشده است. بنابراین، نیاز به توسعهی پروتکل چندپخشی برای VANETها با پشتیبانی مکانیزمهای پایان به پایان QoS وجود دارد که میتواند در یک پروتکل لایه حملونقل اجرا شود.

در این مقاله یک پروتکل قوی مسیریابی خودوریی (ROVER)، که چندپخشی جغرافیایی قابل اعتماد را پیشنهاد میدهد ارائه میکنیم. پروتکل از یک کشف مسیر واکنش فرآیند در یک ZOR استفاده میکند. ما پروتکل را با راهاندازی شبیهسازی واقعی ارزیابی میکنیم. ما یک برنامه انتقال داده در نظر میگیریم، که در آن یک وسیله نقلیه پیام داده را به همه وسایل نقلیه که در یک ZOR مشخص شده است میفرستد. نتایج نشان میدهد که ROVER دادهها را با تاخیر معقول و منطقی 100٪ از وسایل نقلیه برای تقریبا تمام حالات ارائه میکند. همچنین، ROVER میتواند توسط برنامههای کاربردی که نیاز به QoS پایان به پایان دارند توسط اجرای یک پروتکل لایه حملونقل که از درخت multicast برای راهاندازی توسط ROVER استفاده میکند، استفاده شود.

ROVER .2

در این بخش پروتکل مسیریابی ROVER را توصیف میکنیم (مسیریابی خودرویی قوی). بهطورخلاصه تفاوت اصلی بین geocasting و ROVER مشابه تفاوت بین جاری شدن سیل و یک پروتکل فعال MANET مانند AODV است: هر دو در ROVER و در AODV تنها بستهی شناور در شبکه را کنترل میکنند- بستههای داده تک پخشی هستندو بهطور بالقوه کارایی و قابلیت اطمینان را افزایش میدهند. فرض میشود هر خودرو که شماره منحصر به فرد شناسایی خودرو (VIN) دارد. همچنین، وسایل نقلیه دارای یک گیرنده GPS و دسترسی به یک نقشه دیجیتالی دارند. هدف از این پروتکل برای انتقال یک پیام، M، از برنامه، A، به تمام وسایل نقلیه دیگر در یک برنامه ZOR مشخص شده است. ZOR بهعنوان یک مستطیل (اگر چه تعاریف دیگر میتواند بهراحتی جایگزین شود) توسط مختصات گوشهها تعریف شده است. بنابراین، پیام توسط سهگانهی [A، M،Z تعریف شده است. وقتی که یک خودرو یک پیام را دریافت میکند، پیام را میپذیرد اگر، در زمان پذیرشدر در داخل ZOR باشد. مشابه پروتکل geocasting ما یک منطقه از حمل و نقل (ZOF) به عنوان یک منطقه از جمله منبع و ZOR تعریف میکنیم. تمام وسایل نقلیه در ZOF بخشی از فرآیند مسیریابی هستند، اگر چه فقط وسایل نقلیه در ZOR پیام را به لایه کاربرد مربوط به خود ارائه میکنند (توسط A مشخص شده است).

2.1 کشف مسیر

اولین باری که لایه مسیریابی، یک بسته [A، M، Z [ از لایه کاربرد دریافت کرد، یک فرآیند کشف مسیر ایجاد شد. این فرایند آغاز میشود اگر ZOR قبلی دیگر معتبر نباشد. هدف از این فرآیند کشف مسیر، ساخت یک درخت چندپخشی از وسیله نقلیه منبع به تمام وسایل نقلیه در ZOR است.

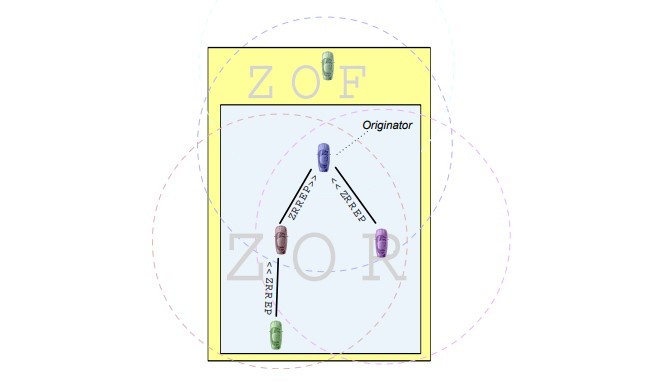

همانطور که در شکل 1 نشان داده شده است، فرآیند کشف مسیر، زمانی که مبتکر خودرو یک پیام درخواست مسیر منطقه (RREQ) حاوی VIN، محل آن، ZOR فعلی، و یک شماره توالی مسیر، SS، در سراسر ZOF آغاز میشود.

Abstract

Vehicular ad-hoc networks (VANETs) offer a large number of new potential applications without relying on significant infrastructure. Many of these applications benefit from multi-hop relaying of information, thus requiring a routing protocol. Characteristics unique to VANETs (such as high mobility and the need for geographical addressing) make many conventional ad hoc routing protocols unsuitable. Also, some envisioned applications have end-to-end QoS requirements. In this paper we propose a new multicast routing protocol specifically designed for VANETs. Its purpose is to provide a routing service for a future reliable transport protocol. We evaluate its performance using realistic network and traffic models. It is shown that it is possible to implement a reliable multicast routing protocol for VANETs.

1 Introduction

For many years research projects have been focused on issues regarding inter-vehicle communication (IVC) systems [1][2][3]. The objective of those projects has been to create the “fully connected vehicle”. By letting vehicles communicate both with each other and with base stations along the road, accidents can be avoided and traffic information can be made available to the driver. Of course, ultimately, the vision is to have in-vehicle Internet access as well. A couple of years ago the term VANET (Vehicular Ad-hoc Network) was introduced, combining mobile ad-hoc networks (MANETs) and IVC systems.

Vehicular Ad-hoc Networks (VANETs) are envisioned to both decrease the number of deaths in traffic and improving the travel comfort by, for example, increasing inter-vehicle coordination. Understandably, the most commonly considered applications are related to public safety and traffic coordination. Collision warning systems and vehicle platooning are two applications that projects work on. Also, traffic management applications, traveller information support and various comfort applications have the potential to make travel (considerably) more efficient, convenient and pleasant.

Most VANET applications require that data is transmitted in a multi-hop fashion, thus prompting the need for a routing protocol. In many aspects, a VANET can be regarded as a MANET. However, the inherent nature of a VANET imposes the following three constraints for a routing protocol:

1. Short-lived links.

2. Lack of global network configuration.

3. Lack of knowledge about a node’s neighbors.

The first issue is due to the mobility of the vehicles. Studies have shown that the lifetime of a link between two nodes in a VANET is in the range of seconds [4]. Similar to a MANET, no central coordinator can be assumed in a VANET. Finally, although a hello protocol (as in OSPF) can be used to discover the neighbors of a node, this may be an expensive and difficult to tune solution. The routing protocol should discover the neighbors as needed. It is also preferable that the routing protocol works for a wide range of applications and traffic scenarios. Several papers propose solutions for specific VANET applications [5][6][7].

Some VANET applications require unicast routing. For example, some envisioned comfort applications, as on-board games and file transfer, will likely need unicast routing with fixed addresses. Many papers have proposed unicast protocols for VANETs. Some papers suggest that VANETs should use already existing unicast protocols for MANETs, as AODV [8][9] or cluster-based protocols [10][11]. Other papers propose new unicast protocols for VANETs [12][13].

However, many VANET applications require position-based multicasting (e.g., for disseminating traffic information to vehicles approaching the current position of the source). A natural match for this type of routing are the geocasting protocols [6][14] that forward messages to all nodes within a Zone of Relevance (ZOR). The geocast concept has been studied for VANETs since the beginning of 1990s [15]. In [16] a geocasting protocol for VANETs was described; in this approach a node forwards a message after a delay that depends on the distance from the last sender. Variants of this protocol have been proposed in [17][18].

The major problem with flooding-based geocasting protocols is that the flooding mechanism is commonly based on broadcast, and it is, thus, best effort. However, some applications will require multicast transmission with end-to-end QoS. Flooding-based geocast protocols are not intended for these types of applications. Therefore, there is a need to develop multicast protocols for VANETs that can support end-to-end QoS mechanisms implemented in a transport layer protocol.

In this paper we present a RObust VEhicular Routing (ROVER) protocol, that offers reliable geographical multicast. The protocol uses a reactive route discovery process within a ZOR. We evaluate the protocol with a realistic simulation setup. We consider a generic data transfer application, in which a vehicle sends a data message to all vehicles within a specified ZOR. The results show that ROVER delivers the data with reasonable delays to 100% of the intended vehicles for almost all scenarios. Also, ROVER could be used by applications that require endto-end QoS, by implementing a transport layer protocol that uses the multicast tree set up by ROVER.

2 ROVER

In this section we will describe the routing protocol ROVER (RObust VEhicular Routing). In short the main difference between geocasting and ROVER is similar to the difference between flooding and a MANET reactive protocol such as AODV: both in ROVER and in AODV only control packets are flooded in the network - the data packets are unicasted, potentially increasing the efficiency and reliability. Each vehicle is assumed to have a unique Vehicle Identification Number (VIN). Also, the vehicles are assumed to have a GPS receiver and access to a digital map. The objective of the protocol is to transmit a message, M, from an application, A, to all other vehicles within an application-specified ZOR, Z. The ZOR is defined as a rectangle (although other definitions can be easily accommodated) specified by its corner coordinates. Thus, a message is defined by the triplet [A, M, Z]. When a vehicle receives a message, it accepts the message if, at the time of the reception, it is within the ZOR. Similar to geocasting protocols we also define a Zone Of Forwarding (ZOF) as a zone including the source and the ZOR. All vehicles in the ZOF are part of the routing process, although only vehicles in the ZOR deliver the message to their corresponding application layer (specified by A).

2.1 Route Discovery

The first time the routing layer receives a packet [A, M, Z] from the application layer, a route discovery process is triggered. The process is also initiated if the previous ZOR is no longer valid. The objective of the route discovery process is to build a multicast tree from the source vehicle to all vehicles within the ZOR Z.

As shown in Figure 1, the route discovery process is initiated when the originator vehicle floods a Zone Route Request (ZRREQ) message containing its VIN, location, the current ZOR, and a route sequence number, SS, throughout the ZOF.

چکیده

1. معرفی

2. ROVER

2.1 کشف مسیر

2.2 انتقال داده

2.3 اتمام مهلت مسیر

3. محیط شبیه سازی

3.1 نرمافزار انتقال اطلاعات

3.2 مدل راه و ترافیک

3.3 مدلهای ارتباطات

3.4 راهاندازی شبیهسازی

4. متریک عملکرد

5. نتایج و بحث

5.1 نسبت تحویل بسته (PDR)

5.2 زمان تحویل بسته (TD)

5.2.1 تراکم خودرو

5.2.2 محدودهی انتقال رادیو

5.2.3 ارتباط منطقه

6. نتیجهگیری

منابع

Abstract

1 Introduction

2 ROVER

2.1 Route Discovery

2.2 Data Transfer

2.3 Route Timeout

3 Simulation Environment

3.1 A Data Transfer Application

3.2 Road and Traffic Models

3.3 Communication Models

3.4 Simulation Setup

4 Performance metrics

5 Results and Discussion

5.1 Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR)

5.2 Packet Delivery Time (TD)

5.2.1 Vehicle Density

5.2.2 Radio Transmission Range

5.2.3 Zone of Relevance

6 Conclusions

References