دانلود رایگان مقاله بارگذاری همزمان و نظارت ساختاری بر دکل سکان الیاف کربن

چکیده

پلاستیک های تقویت شده با الیاف کربن به دلیل استحکام بالا و رفتار خستگی عالیشان، در سازه های دریایی سبک مورد استفاده قرار می گیرند. در این مقاله، یک روش نوآورانه برای بارگذاری همزمان و نظارت ساختاری بر یک دکل سکان پلاستیکی تقویت شده با الیاف کربن را به عنوان بخشی از یک کشتی بزرگ تجاری ارائه خواهیم کرد. نتایج تجربی در اینجا از یک آزمون کششی شبه استاتیک ارائه شده است که در آن نظارت بر بار با استفاده از سنسورهای کرنشی تعبیه شده انجام می شود. نظارت ساختاری، مبتنی بر طیف سنجی امپدانس الکترومکانیکی فرکانس بالا همراه با پردازش سیگنال اختصاصی و مبدل های پیزوالکتریک نصب شده در سطح است. ما به نتایج زیر رسیده ایم: (1) نمایش سیستم نظارت ترکیبی شامل بار و نظارت ساختاری، (2) جاسازی موفقیت آمیز کرنش سنج ها در طول تولید کامپوزیت دکل سکان پلاستیکی تقویت شده با الیاف کربن، (3) توسعه سخت افزار ابزار دقیق برای اندازه گیری امپدانس الکترومکانیکی چند کاناله، و (4) تشخیص موفقیت آمیز آسیب با استفاده از طیف سنجی امپدانس الکترومکانیکی در نمونه های ضخیم بدنه سکان پلاستیکی تقویت شده با الیاف کربن با استفاده از داده های کرنش.

مقدمه

در کاربردهای بیشتر و بیشتر در سازه های دریایی، مخلوط های چند ماده برای ساختن سازه های کارآمد همراه با مزایایی در وزن و عملکرد انتخاب می شوند. پلاستیک های تقویت شده با الیاف کربن (CFRPs) به دلیل استحکام بالا و به خصوص رفتار خستگی عالی، می توانند ماده مناسبی برای بخش های با بارگذاری بالا باشند. در این مقاله، یک دکل سکان در CFRP برای یک کشتی بزرگ تجاری در نظر گرفته شده، همانطور که در شکل 1 نشان داده شده است، جایی که تیغه سکان باید با فشار مناسب به دکل متصل شود. این فشار مناسب باعث ایجاد تنش های زیاد در جهت شعاعی دکل می شود، که عمود بر جهت الیاف یک لوله CFRP آسیب دیده با رشته مرطوب است. به عنوان یک نتیجه، قسمت CFRP از دکل سکان باید به قطعات فلزی متصل شود، که می توانند تیغه سکان را به دکل وصل کنند. این امر منجر به تمرکز تنش زیاد بین قطعات فلزی و CFRP می شود، به طوری که این مناطق اغلب بحرانی هستند (Piggott، 1989؛ Wang et al.، 2017). در اجزای CFRP با ضخامت دیواره بسیار زیاد، وضعیت تنش در مقایسه با قطعات CFRP با دیواره نازک پیچیده تر بوده و پیش بینی مکانیک شکست دشوار است. این بدان معنی است که یک بار پیوسته و نظارت ساختاری برای چنین اجزای CFRP ضخیم به شدت مورد نیاز است.

چندین نمونه در متن یافت می شود که در آن یک نظارت بر بار با استفاده از سنسورهای تعبیه شده با نظارت بر سلامت ساختاری (SHM) در همان سازه ترکیب شده است (Bosse and Lechleiter، 2016؛ Ling and Mahadevan، 2012؛ Yuan et al.، 2006). کارهای قبلی در مورد سازه های کشتی عمدتاً بر نظارت بر بار یا نظارت ساختاری معطوف بوده است. اصول گسترده ای که برای نظارت بر بار استفاده می شود، مبتنی بر کرنش سنج های مقاومتی یا نوری (شبکه براگ الیاف) است (Torkildsen و همکاران ، 2005). علاوه بر این، شتاب سنج ها توسط فلپس و موریس (2013) برای تشخیص رفتار مرتعش سراسری (حرکت لنگری) استفاده شده است. چنین رویکردهای نظارت بر بار امکان تخمین مدت زمان عمر باقیمانده سازه ها را فراهم می کند و بازخورد فوری را به اپراتور می دهد تا تغییرات زمان واقعی در مانور را برای به حداقل رساندن فراتنش ایجاد کند (فلپس و موریس، 2013).

با این حال، چندین روش SHM برای سازه های کشتی در متن گزارش شده است. اوکاشا و همکاران (2010) یکپارچگی SHM را در ارزیابی عملکرد چرخه عمر سازه های کشتی تحت عدم قطعیت نشان دادند. مدل مبتنی بر SHM بدنه های کشتی نیروی دریایی توسط استول و همکاران نشان داده شده است (2011). یک سیستم SHM بی سیم برای سازه های زیر دریایی توسط Nugroho و همکاران ارائه شده است (2016). شناسایی آسیب در ساختارهای پوسته ای غوطه ور شده با استفاده از الگوریتم تکامل افتراقی توسط رید و همکاران انجام شده است (2013). سیستم نظارت چند منظوره برای کشتی های یخ شکن توسط ژیرنوف و همکاران ارائه شده است (2016).

روش SHM نویدبخش با استفاده از روش امپدانس الکترومکانیکی (EMI) ارائه شده است که برای اولین بار توسط لیانگ و همکاران شرح داده شد (1994). روش EMI بر اساس این واقعیت است که امپدانس الکتریکی یک تکه پیزوالکتریک با امپدانس مکانیکی ساز ه ای که به آن پیوند یافته، مرتبط است. در عمل، اغلب از معکوس امپدانس پیچیده، یعنی گذارایی Y استفاده می شود. EMI با موفقیت برای تشخیص تورق (لایه لایه شدگی) به طور مصنوعی ایجاد شده در مواد کامپوزیتی مورد استفاده قرار گرفته است (Ostachowicz و همکاران ، 2017). همچنین با استفاده از روش EMI می توان آسیب ساختاری در یک اتصال تزریق شده را تشخیص داد (Moll، 2018). مروری بر تحولات اخیر روش EMI در حوزه های مختلف کاربردی توسط وندوفسکی و همکاران ارائه شده است (2017). با بهترین دانش نویسندگان، تنها یک نشریه وجود دارد که از روش EMI در کشتی ها با تمرکز بر روی سازه های خرپایی آلومینیومی استفاده می کند (گریسو ، 2013).

به خوبی شناخته شده است که طیف های EMI به عوامل بیرونی ازقبیل دما (واندوفسکی و همکاران ، 2017)، بار سازه (Annamdas et al.، 2007؛ Taylor et al.، 2013) و ضخامت/سفتی چسب (Islam and Huang، 2014؛ Tinoco and Rosas-Bastidas، 2016؛ Tinoco and Serpa، 2011) بستگی دارد. جبران این اثرات برای جلوگیری از مثبت های کاذب در تشخیص آسیب بسیار مهم است. خرابی های مبدل در اثر شکست یا گسیختگی و همچنین عوامل محیطی تأثیر بیشتری بر بخش تصوری گذارایی نسبت به بخش واقعی دارد (Giurgiutiu and Zagrai، 2000).

همکاری های جدید این مقاله توسط موارد زیر آورده شده است:

1. نمایش سیستم نظارت هیبریدی در ترکیب با بار و نظارت ساختاری. بنابراین، نمونه های ضخیم CFRP از دکل سکان در یک آزمون کششی شبه استاتیک تولید شده و مورد مطالعه قرار گرفته است.

2. جاسازی موفقیت آمیز کرنش سنج های طی تولید کامپوزیت دکل سکان.

3. توسعه سخت افزار ابزار دقیق برای اندازه گیری های EMI چند کاناله. برخلاف دستگاه های موجود، سخت افزار اندازه گیری ارائه شده از فرکانس های بالا (حداکثر 1 مگاهرتز) و جریان های زیاد (حداکثر A2) پشتیبانی می-کند، به طوری که می توان مواد بسیار سبک مانند دکل سکان CFRP پیشنهادی را بازرسی کرد.

4. بحث در مورد ترکیب موفقیت آمیز بار و نظارت ساختاری برای تشخیص آسیب با استفاده از طیف سنجی EMI در نمونه های ضخیم دکل سکان CFRP. وابستگی نشانه های EMI به موارد بار را می توان با استخراج اطلاعات بار از کرنش سنج های جاسازی شده حذف کرد.

باقیمانده این مقاله به روش زیر سازماندهی می شود. بخش "تکنیک های اندازه گیری بار و نظارت ساختاری" تکنیک های اندازه گیری برای نظارت بر بار و نظارت ساختاری را ارائه می دهد. پس از آن، بخش "راه اندازی تجربی" آماده سازی تجربی آزمون کشش شبه استاتیک شامل توصیفی از نمونه های دکل سکان را شرح می-دهد. نتایج حاصل از مفهوم نظارت هیبریدی در بخش "نتایج تجربی" ارائه شده و پس از آن بحثی در بخش "بحث و گفتگو" انجام می شود. سرانجام، نتیجه گیری ها در بخش "نتیجه گیری" ارائه می شود.

تکنیک های اندازه گیری برای بار و نظارت ساختاری

نظارت بر بار با استفاده از کرنش سنج های تعبیه شده

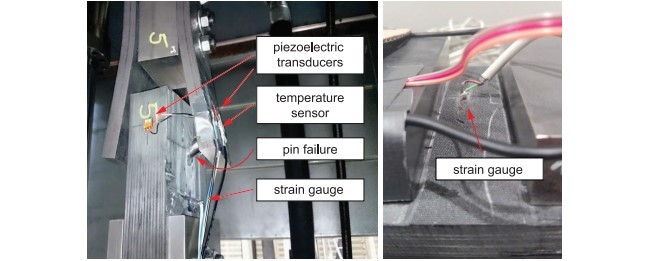

نظارت بر بار با کرنش سنج LI66-10 / 350 توسط HBM که به طور مستقیم در بین لایه های کامپوزیت تعبیه شده، انجام می شود. این سنسور دارای ابعاد کلی 22 × 10 میلی متر است. به دلیل یکپارچه بودن، یک لوله CFRP در دو مرحله مختلف تولید می شود. در حالت اول، لمینیت رزوه شده و تا ضخامتی که سنسورها در آن قرار دارند، پخته می شوند. در سطح پدیدار شده، سنسورها در قسمت مرکزی نمونه نهایی قرار دارند (شکل 7 را ببینید). از یک چسب اپوکسی (Hardman Double Bubble Epoxy Hardman)، که از نظر شیمیایی بسیار شبیه به رزین است، برای تثبیت کرنش سنج ها برای سیم پیچ رشته ای مرطوب CFRP استفاده شد. ضخامت فیلم چسبنده چند میکرون است. سنسورها دارای پین های اتصال به طرف خارج هستند (شکل 8 را ببینید)، که امکان پیچاندن قسمت دوم لمینت CFRP بدون از دست دادن دسترسی به سنسور را می دهد. پس از آن، سنسور در صفحه لمینت، جایی که کرنش جالب توجهی در آن رخ می دهد، قرار گرفته و لمینیت بخش دوم رزوه شده و تا ضخامت نهایی پخته می شود. شکل 2 سنسورهای چسبیده را در سمت چپ و لمینت را قبل از مرحله نهایی پخت در سمت راست نشان می دهد.

Abstract

Carbon-fiber-reinforced plastics are widely used in lightweight marine structures due to their high strength and superior fatigue behavior. In this article, we will present an innovative methodology for simultaneous load and structural monitoring of a carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic rudder stock as part of a big commercial vessel. Experimental results are presented here from a quasi-static tensile test in which the load monitoring is performed using embedded strain sensors. Structural monitoring is based on high-frequency electromechanical impedance spectroscopy combined with dedicated signal processing and surface-mounted piezoelectric transducers. We have achieved the following results: (1) the demonstration of a hybrid monitoring system including load and structural monitoring, (2) successful embedding of strain gauges during composite manufacturing of the carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic rudder stock, (3) development of instrumentation hardware for multichannel electromechanical impedance measurements, and (4) successful damage detection by means of electromechanical impedance spectroscopy in thick carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic rudder stock samples exploiting strain data.

Introduction

In more and more applications within maritime structures, multimaterial mixes are chosen to build efficient structures with advantages in weight and performance. Due to their high strength and especially their superior fatigue behavior, carbon-fiber-reinforced plastics (CFRPs) can be an appropriate material for highly loaded parts. This article considers a rudder stock in CFRP for a big commercial vessel, as shown in Figure 1, where the rudder blade needs to be connected to the stock by press fit. This press fit causes high stresses in the radial direction of the stock, which is perpendicular to the fiber direction of a wet filament wounded CFRP tube. As a consequence, the CFRP part of the rudder stock must be connected to metallic parts, which are able to couple the rudder blade to the stock. This leads to a high stress concentration between metallic and CFRP parts, so that these areas are often most critical (Piggott, 1989; Wang et al., 2017). In CFRP components with very high wall thicknesses, the stress state is often more complex compared to thin-walled CFRP parts and it is difficult to predict the fracture mechanics. This means that a continuous load and structural monitoring for such thick CFRP components is strongly needed.

Several examples can be found in the literature where a load monitoring with embedded sensors is combined with structural health monitoring (SHM) of the same structure (Bosse and Lechleiter, 2016; Ling and Mahadevan, 2012; Yuan et al., 2006). Previous works on ship structures have mainly focussed either on load monitoring or structural monitoring. The most widely used principles for load monitoring are based on resistive or optical (fiber Bragg grating) strain gauges (Torkildsen et al., 2005). Moreover, accelerometers have been used by Phelps and Morris (2013) to detect global resonant behavior (whipping). Such loadmonitoring approaches enable the estimation of the structures’ remaining life time and provide immediate feedback to the operator to allow real-time changes in maneuvering to minimize overstressing (Phelps and Morris, 2013).

However, several SHM techniques for ship structures have been reported in the literature. Okasha et al. (2010) show the integration of SHM in life-cycle performance assessment of ship structures under uncertainty. Model-based SHM of naval ship hulls is demonstrated in Stull et al. (2011). A wireless SHM system for submarine structures is presented in Nugroho et al. (2016). Damage identification in submerged shell structures by means of a differential evolution algorithm has been performed in Reed et al. (2013). A multipurpose monitoring system for icebreakers is presented in Zhirnov et al. (2016).

A promising SHM approach is given by the electromechanical impedance (EMI) method that was first described in Liang et al. (1994). The EMI method is based on the fact that the electrical impedance of a piezoelectric patch is linked to the mechanical impedance of the structure it is bonded to. In practice, the inverse of the complex impedance, the admittance Y, is often used. EMI has been successfully used for the detection of artificially induced delamination in composite materials (Ostachowicz et al., 2017). Structural damage in a grouted connection can also be detected by the EMI approach (Moll, 2018). A review on recent developments of the EMI method in different application domains is presented in Wandowski et al. (2017). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is only one publication that employs the EMI method on ships by focussing on aluminum truss structures (Grisso, 2013).

It is well known that EMI spectra depend on external factors such as temperature (Wandowski et al., 2017), load of the structure (Annamdas et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2013), and the thickness/stiffness of the adhesive (Islam and Huang, 2014; Tinoco and RosasBastidas, 2016; Tinoco and Serpa, 2011). The compensation of these effects is crucial to avoid false-positives in damage detection. Transducer failures by breakage or debonding as well as environmental factors have a higher impact on the imaginary part of the admittance than on the real part (Giurgiutiu and Zagrai, 2000).

The novel contributions of this article are given by the following items:

1. Demonstration of a hybrid monitoring system combining load and structural monitoring. Therefore, thick CFRP samples of a rudder stock have been manufactured and studied in a quasi-static tensile test.

2. Successful embedding of strain gauges during composite manufacturing of the CFRP rudder stock.

3. Development of instrumentation hardware for multichannel EMI measurements. In contrast to available devices, the presented measurement hardware supports high frequencies (up to 1 MHz) and high currents (up to 2A) so that highly attenuated materials such as the proposed CFRP rudder stock can be inspected.

4. Discussion of the successful combination of load and structural monitoring for damage detection by means of EMI spectroscopy in thick CFRP rudder stock samples. The dependency of the EMI signatures on the load cases can be eliminated by exploiting the load information from embedded strain gauges.

The remainder of this article is organized in the following way. Section ‘‘Measurement techniques for load and structural monitoring’’ presents the measurement techniques for load monitoring and structural monitoring. Subsequently, section ‘‘Experimental setup’’ describes the experimental setup of the quasi-static tensile test including a description of the rudder stock samples. Results for the hybrid monitoring concept are presented in section ‘‘Experimental results’’ followed by a discussion in section ‘‘Discussion.’’ Finally, conclusions are drawn in section ‘‘Conclusion.’’

Measurement techniques for load and structural monitoring

Load monitoring with embedded strain gauges

The load monitoring is realized by embedding the strain gauge LI66-10/350 by HBM directly among composite layers. The sensor has a total size of 22 mm 3 10 mm. For the sake of integration, a CFRP tube is manufactured in two different steps. In the former, the laminate is wound and cured up to the thickness where the sensors are then placed. On the emerging surface, the sensors are located in the central part of the final specimen (see Figure 7). An epoxy glue (Hardman Double Bubble Epoxy), chemically very similar to the resin, was used to fix the strain gauges for the wet filament winding of the CFRP. The thickness of the adhesive film is few microns. The sensors have connection pins facing outwards (see Figure 8), making it possible to wind the second part of the CFRP laminate without losing access to the sensor. After that, the sensor is positioned on the laminate plane, where the interesting strain occurs, and the laminate of the second part is wound and cured up to the final thickness. Figure 2 shows the glued sensors on the left and the laminate before final curing step on the right.

چکیده

مقدمه

تکنیک های اندازه گیری برای بار و نظارت ساختاری

نظارت بر بار با استفاده از کرنش سنج های تعبیه شده

طیف سنجی EMI

راه اندازی آزمایشی

نتایج تجربی

بحث

نتیجه گیری

منابع

Abstract

Introduction

Measurement techniques for load and structural monitoring

Load monitoring with embedded strain gauges

EMI spectroscopy

Experimental setup

Experimental results

Discussion

Conclusion

References