دانلود رایگان مقاله شرکت های رقابتی در مناطق کم جمعیت نروژ

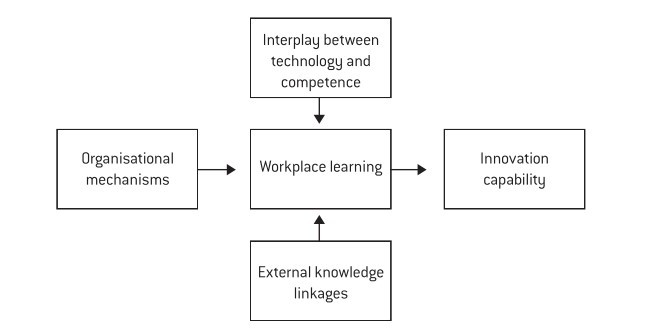

اين مقاله از مطالعات تجربي دو شركت رقابتي در منطقه ي سازماني كم جمعيت در نروژ گرفته مي شود. پرسش اصلي در مقاله اين است كه اين شركت ها چگونه به رقابت پذيري جهاني دست يافته اند. اين مقاله بر روي اين پرسش متمركز شده است كه شركت ها چگونه با توجه ويژه بر آموزش سازماني شركت ها و ظرفيت جذب، نوآوري هاي خود را سازماندهي مي كنند. به اين نكته نيز دست يافته شده است كه يادگيري در محل كار، شركت ها را قادر مي سازد كه از دانش در راه غير مرسوم آن نيز استفاده نمايند. اين آموزش؛ در جنبه ها و ويژگي هاي خاص سازماني در شركت ها همچون مشاركت گسترده، آموزش دراز مدت كار، استفاده از دانش هاي عمل محور در پروژه هاي ابتكاري و نوآوري ها و اتصال و پيوند با منابع علمي ملي و جهاني نهفته است. ويژگي هاي مناطق كم جمعيت نشان مي دهد كه اين ويژگي ها يك استراتژي كلي قابل اعمال را در چنين منطقه هايي باعث مي شود.

مقدمه

در اين مقاله اين موضوع را مورد بحث قرار مي دهيم كه شركت ها در مناطق كم جمعيت براي رقابت به يادگيري در محل كار بستگي دارد. محل سكونتشان نشان مي دهد كه نمي توانند به آنها نمی توانند مانند شركت ها در سطح مناطق مركزي به منابع محلی خارج از شركت تکیه كنند. تمرکز ما بر روی یادگیری در محل کار به موازات مشارکت های اخیر ادبی می باشد. Ekman et al. (2011) به سازمان نوآوری و روند یادگیری در سطح شرکت در میان ساختارهای آموزشی و اجتماعی فرهنگی در جوامع اسکاندیناوی - که مشارکت گسترده را شبیه سازی میکند- اشاره میکند. بر اساس اطلاعات گشترده ی اروپایی، Lorenz (2011) مشخص کرد که کشورهای نروژ، دانمارک، و سوییس (و هلند) تعداد بالای قابل مقایسه ای از آموزش های سازمانی دارند. این ها با تنوع در امور، عدم محوریت مسئولیت ها و تصمیمات، فرصت هایی برای استفاده از ابتکار عمل در کارگاه ، و ادغام یادگیری و تغییرات در کار مشخص می شوند. Gustavsen (2011) به این نوع سازمان به عنوان کاری مناسب که به طور گسترده در میان مدل های مشترک اروپا گسترش یافته و به عنوان پاسخی به تاکیدات قبلی بر روی سازمان های کار فوردی (Fordist) اشاره میکند. سازمان کار آموزش،استفاده بیشتر از تجربه و تخصص کارکنان، و ابتکار عمل در روند نوآوری را ممکن میسازد. علاوه بر این جوامع رفاهی ترفدار مساوات به اعتماد و جریان دانش در داخل و بین سازمان -که روند و پوروسه ی نوآوری را شبیه سازی می کنند- کمک میکنند. Lundvall & Lorenz (2012) اظهار میکند که سطوح بالای سرمایه ی اجتماعی و اعتماد در کشورهای شمال اروپا باعث افزایش نوآوری، تولیدات بالا، و رشد اشتغال زایی در این کشورها میگردد.

کلان مطالعاتی که در بالا اشره شد، نشان می دهد که آموزش در محل کار برای رقابت پذیری شرکت ها و ارتباط این آموزش ها و یادگیری ها با ویژگی های جوامع شمال اروپا همچون فاکتورهای فرهنگی، ساختارهای آموزشی، سرمایه ی اجتماعی و اعتماد حائز اهمیت است. گرچه این مطالعات فاقد یک مشی جغرافیایی ورای سطح ملی است که به جهت تفاوت تاثیر آموزش در محل کار، در مناطق محلی، با اهمیت است. این در جایی ست که جغرافیای اقتصادی می تواند به دانش تئوری در مورد نواحی و سیستم ابتکاری ناحیه ای کمک کند. همچون گونه شناسی Trippl و Tödtling برای ویژگی های سازمانی سیستم ابتکار محلی. در تحقیق حاضر ما مفهوم " مناطق کم جمعیت " را برای اشره بر مناطقی استفاده میکنیم که سیستم نوآوری محلی به طور سازمانی کم جمعیت است.در یک منطقه ی کم جمعیت دسته های پیشرفت صنعتی وجود ندارد و یا دارای بخش ضعیف تولید دانش و سازمان های پخش میباشد. بنابراین این ویژگی ها باعث می شود تبادل دانشی محلی در سطح کوچک و کم اتفاق بیفتد و در نتیجه فعالیت نوآوری بر اساس منابع محلی کم خواهد بود. بسیاری از تحقیقات گذشته بر بروی مناطق پر جمعیت سازمانی متمرکز شده اند، همچون دسته ها و خوشههای منطقه ای که شرکت ها تا حدی میتوانند فعالیت های نوآوری خود را براساس نظریات تخصصی خارجی و سایر منابع بنا نهند.

هدف ما پیشرفت در فهم فعلی نقشی است که سازمان های فعالیت نوآوری و پیشرفت کار در شرکت های واقع در مناطق کم جمعیت در قدرت رقابت پذیری شرکت ها ایفا می کنند. بنابراین مسئله ی مورد بحث ما سطح شرکت است، بخصوص یادگیری در محل کار. گرچه ما تحلیل ها را در سطح شرکت و سطح سیستم ترکیب می کنیم. (که به عنوان سیستم ابتکار و نو آوری سازمانی مناطق کم جمعیت متصور شده است ). پرسش تحقیق ما این است که : چگونه شرکت های واقع در مناطق کم جمعیت نروژی از طریق تمرین های یادگیری در محل کار به رقابت پذیری دست می یابند؟ در ادامه ی قسمت تئوری مفهوم یادگیری در محل کار در سطح عمیق تر مورد بحث و بررسیقرار می دهیم و در قسمت های بعد که شامل مفاد بحث میگردد به توضیح در مورد منطقه و مطالعه ی موردی شرکت ها (شرکت های مورد بحث) میپردازیم.

یادگیری سازمانی و جغرافیای اقتصادی

در این بخش مفاهیمی را نشان میدهیم که در تحلیل موارد استفاده میشود. چارچوب نظری در تقابل بین جغرافیای اقتصادی و یادگیری سازمانی، با تاکید بر مورد دوم نهفته است.

نواوری ها تنها تنها رشد متناوب ممکن برای اقتصادهای پیشرفته ی پرهزینه اند. در اقتصاد افزایشی جهانی،شرکت ها نمی توانند روی هزینه های پایین رقابت کنند، آنها نیاز به محصولات متفاوت، تولیدات بالا و سازمانی هوشمند دارند. ( آن ها میبایست مبتکر و خلاق باشند) فعالیت ابتکاری(نوآوری) به طور اصلی بر سه فاکتور بنا شده است. ابتدا شرکت ها باید شایستگی ها و ظرفیت های درونی خاص و منحصر به فردی را ایجاد کنند که این بدان معناست که سازمان دانشی و روند و پوروسه ی یادگیری درون شرکتی از اهمیت به سزایی برخوردار است. سپس شرکت ها باید دانش مکمل خارجی را وارد کنند. چرا که فعالیت ابتکاری روندی تعاملی و پویاست که در شبکه ی نسبتا پایدار خصوصی و عمومی انجام می پذیرد. و سوم، فعالیت ابتکاری شبیه سازی شده و توسط تنظیمات وسیع تری چون قواعد و قوانین، توسعه ی بازار، پیشرفت های تکنولوژیکی و موسسات (به معنای قوانین بازی) متوقف شده است. ما به هر سه فاکتور اشاره میکنیم: در شرکت ها و شبکه های خلاق چه میگذرد؟ آن ها از بودن در مناطق کم جمعیت و مدل یادگیری سازمانی شمال اروپا چگونه تاثیر پذیرفته اند؟

پل های ارتباطی دانش

در میان جغرافیای اقتصادی و مسیر دستیابی به سیستم ابداع کردن، نوع و جغرافیای پل های ارتباطی علمی بصورت مشخص و مفصل بحث شده اند (کیبل 2000، گرتلر و ولف 2004، ماسکل و همکارانش 2006، تریپل و همکارانش2009). مسیر دستیابی به سیستم ابداع کردن بر پایه این حقیقت ساخته می شود که شرکت های ابداعی بایستی شایستگی های منحصر به فرد را توسعه داده و این که آن ها شایستگی مکمل خارجی را بدست آورده و شبیه سازی کرده و توسط شرایط بیرونی محدود و متوقف شوند. یک خروجی از بحث یک دورنمای کمی متفاوت بر پل های ارتباطی دانش مانند تفاوت بین انتقال گرهای اطلاعات استاتیک (برای مثال متنو کد بندی شده از طریق کتاب و اینترنت) و فرایندهای یادگیری دینامیک در میان و بین سازمان دهی ها. در هر حال بحث تاریخ گذاری شامل جدا کردن واضح میان انواع مختلف دانش داخلی و خارجی و چگونگی ترکیب این انواع در فرایند ابداع می باشد. بنابراین ما مباحثی در مقاله یادگیری سازمان دهی شده درباره دانش همانند یک پدیده اجتماعی و درباره یادگیری سازمان دهی شده و ظرفیت قابل جذب می ارائه می دهیم.

دانش به عنوان یک پدیده اجتماعی

قضاوت های بکر- ریترسپاک (2006) مسیر جریان یافتن دانش برای عملکرد دانش بنیان برای داشتن خواص شبه مایع می باشد که مشخصه های لوله ها و تسهیلات ذخیره سازی شارها را اندازه گیری می کنند. از این دیدگاه دانش به عنوان یک دارایی که می تواند به راحتی انتقال یابد، با نادیده گرفتن طبیعت اجتماعی کاراکتر جایگذاری شده از دانش می باشد. جریان جدیدی از تحقیقات ارائه شده است که در آن ها تعداد مکان یابی شده و و جایگذاری شده از طبیعت دانش قرار داده شده است. اول، تحقیق بر روی این موضوع که دانش یک پدیده اجتماعی است که ابداعات جدید را بصورت ویژه بکار می گیرد. یک چرخش بر پایه کار عملی توسط لاو و ونگر (1991) انجام گرفته است که آن ها ارتباط بین عملیات ها را شناسایی کردند همانند جایی که کار و آموزش در یک شرکت یا موسسه به وقوع می پیوندد. برون و دوگویید (1991) این جنبه را در یک تجارت توسعه داده و پیشنهاد داده اند که نیاز برای کار، آموزش و ابداع کردن بصورت یکپارچه در سازمان ها وجود دارد. این ارتباط عملیات کردن است که دانش استفاده شده و بوجود آورده است.

یکی دیگر از تحقیقات جریان یافتن دانش تجربیات در حل مسائل گروه ها و دریافتن این که این راه حل مشکلات پیچیده بصورت فزاینده نیاز به توانایی برای ترکیب دانش حمایت کننده فردی با چشم اندازهای دور وسیع و گسترده می باشد. در این مسیر دانش نیاز به استفاده در عمل برای حل مشکلات جدید از طریق برهم کنش های بین افراد می باشد. در یک مطالعه نژادی بر روی کار که شامل تولید یک محصول جدید می باشد، بچکی (2003) پیشنهاد داده است که به اشتراک گذاری دانش در میان اشخاص، جوامع و ارتباطات یا سازمان هامی تواند به جهت شمارش یک فرایند انتقال دانش باشد. سوء تفاهم ها با توسعه یک زمینه رایج رفع می گردند، بر پایه آن چیزی که ممکن است برای ساخت یک درک غنی تر از محصول و مشکلات خاص استفاده شوند. با این وجود، دانش از طریق انتقال قابل به اشتراک گذاشتن نیست اما بیشتر از این از طریق یک فرایند انتقال این قابلیت را دارا می باشد.

The article departs from empirical studies of two competitive firms in an organisationally thin region in Norway. The main question in the article is how these firms have achieved global competitiveness. The article focuses its inquiry on how the firms organise their innovation activity, giving special attention to the firms’ organisational learning and absorptive capacity. It is found that find that workplace learning enables the firms to utilise knowledge in uncommon ways. The learning rests on specific organisational traits in the firms, such as broad participation, long-term on-the-job training, the use of practice-based knowledge in innovation projects, and links to national and global knowledge sources. The characteristics of thin regions indicate that these traits make up a generally applicable strategy in such regions.

Introduction

In this article we argue that firms in thin regions depend on workplace learning in order to be competitive. Their location suggests that they cannot rely on local resources outside the firm to the same degree as firms in core regions. Our focus on workplace learning parallels recent contributions to the literature. Ekman et al. (2011) point to the organisation of innovation and learning processes both at the firm level and within the sociocultural and institutional structures of Nordic societies – which stimulate broad participation – as important factors behind the strong economic performances of Nordic countries. On the basis of extensive European data, Lorenz (2011) reveals that Norway, Denmark, and Sweden (and the Netherlands) have a comparatively high number of learning organisations. These are characterised by variations in tasks, decentralisation of responsibilities and decisions, opportunities for use of initiative on the shop floor, and integration of learning and changes in work. Gustavsen (2011) refers to this type of organisation as the good work that was largely developed through the Nordic collaborative model and as a response to the previous emphasis on Fordist work organisations. The learning work organisation enables greater use of employees’ expertise, experience, and initiative in innovation processes. In addition, egalitarian welfare societies contribute to trust and knowledge flow within and between organisations, which also stimulates innovation processes. Lundvall & Lorenz (2012) thus maintain that high levels of social capital and trust in the Nordic countries trigger incremental innovations, high productivity, and job growth in these countries.

The above-mentioned macro-studies demonstrate that workplace learning matters for firms’ competitiveness and that this learning is linked to characteristics of Nordic societies, such as cultural factors, institutional structures, social capital, and trust. However, the studies lack a geographical approach beyond the national level, which is important because subnational regions differ in ways that affect workplace learning. This is where economic geography can contribute with theoretical knowledge about regions and regional innovation systems, such as Tödtling & Trippl’s (2005) typologies for organisational characteristics of regional innovation systems. In this article we use our concept ‘thin region’ to denote regions in which the regional innovation system is organisationally thin (Tödtling & Trippl 2005). A thin region has either no or weakly developed industrial clusters and a weak endowment of knowledge generation and diffusion organisations. These characteristics lead to little local knowledge exchange and little innovation activity based on regional resources. Many earlier studies have focused on organisationally thick regions, such as regional clusters, where firms can to some extent base their innovation activity on nearby external expertise and other resources (Porter 1998).

We aim to improve current understanding of the role that the organisation of innovation activity and improvement work in firms located in thin regions has in the firms’ competitive strength. Hence, our unit of analysis is the firm level, specifically workplace learning in firms. However, we also combine analyses at the firm level and the system level (conceptualised as an organisationally thin regional innovation system). Our research question is: How do firms located in a thin Norwegian region achieve competitiveness through their workplace learning practice? In the following theoretical section we explore the concept of workplace learning in more depth and in the context section we discuss the region and the case-study firms.

Organisational learning and economic geography

In this section we present and discuss concepts that are used in the case analyses. The theoretical framework lies in the intersection between economic geography and the organisational learning literature, with an emphasis on the latter, since the unit of analysis is the firm level.

Widely defined, innovations are the only long-term, sustainable growth alternative for developed, high-cost economies. In an increasingly global economy, firms in such countries cannot compete on low costs; they need to have differentiated products, high productivity, and smart organisation (i.e. they need to be innovative). Innovation activity is mainly based on three factors (Edquist 2005). First, firms have to build some unique internal competence and capability, which means the organisation of knowledge and learning processes inside firms is of vital importance. Second, firms have to bring in external complementary knowledge, as innovation activity is an interactive and dynamic process carried out within a fairly stable network of private and public actors (Lundvall 2007). Third, innovation activity is stimulated and hampered by ‘the wider setting’ (Edquist 2005), such as rules and regulations, market development, technological advances, and institutions (in the meaning of ‘rules of the game’). We address all three factors: what goes on inside innovative firms and in innovation networks, how they are influenced by being in a thin region, and the ‘Nordic learning organisation model’.

Knowledge linkages

Within economic geography and the innovation system approach, the type and geography of knowledge linkages have been intensely discussed (Keeble 2000; Gertler & Wolfe 2004; Maskell et al. 2006; Trippl et al. 2009). The innovation system approach builds upon the fact that innovative firms have to develop unique competences and that they acquire external supplementary competence and are stimulated and hampered by external conditions. One outcome of the discussion is a more nuanced perspective on knowledge linkages, such as the distinction between static information transfer (e.g. codified text through books and the Internet) and dynamic learning processes within and between organisations. However, the discussion to date has not involved a clear-cut distinction between different types of internal and external knowledge and how these types are combined in innovation processes. We therefore present the discussions in the organisational learning literature about knowledge as a social phenomenon and about organisational learning and absorptive capacity.

Knowledge as a social phenomenon

Becker-Ritterspach (2006) criticises the flow-of-knowledge approach for treating knowledge for having liquid-like properties, wherein the characteristics of pipelines and storage facilities determine the flows. From this perspective, knowledge is treated as an asset that can easily be transferred, ignoring the social nature and embedded character of knowledge. New streams of research have emerged, which take into account the situated and embedded nature of knowledge. First, research has demonstrated that knowledge is a social phenomenon in which practice underlies innovation. A practice-based orientation has been supported by Lave & Wenger (1991), who identify ‘communities-ofpractice’ as the place where work and learning happen in a firm. Brown & Duguid (1991) develop this concept in a business context and suggest there is a need for working, learning, and innovating to be unified in organisations. It is through communities-of-practice that knowledge is used and created.

Another research stream examines knowledge in problemsolving groups and recognises that solving increasingly complex problems requires the ability to combine the knowledge held by individuals with diverse perspectives. In this approach, knowledge needs to be used in practice in order to solve novel problems through interactions between individuals. In an ethnographic study of the work involved in the production of a new product, Bechky (2003) suggests that knowledge-sharing among individuals, communities, or organisations can be looked upon as a process of knowledge transformation. Misunderstandings are avoided by developing a common ground, on the basis of which it is possible to create a richer understanding of the product and the specific problems. Hence, knowledge is not shared through transfer but rather through a process of transformation.

مقدمه

یادگیری سازمانی و جغرافیای اقتصادی

پل های ارتباطی دانش

دانش به عنوان یک پدیده اجتماعی

یادگیری سازمان دهی و منبع یابی دانش

روش و داده

شرکت های رقابتی در یک منطقه کم جمعیت

آنالیز موردی

ریخته گری آلومینیوم فارسوند

مکانیزم های یادگیری سازمانی

اثر متقابل بین تکنولوژی و دانش بر پایه تجربه

ظرفیت های ابداع کنندگی

پل های ارتباطی دانش

اندرسون مکانیسک ورکستد

مکانیزم های یادگیری سازمان دهی شده

اثر متقابل بین تکنولوژی و دانش بر پایه تجربه

ظرفیت های ابداعی

پل های ارتباطی دانش

بحث

موارد نتیجه گیری

منابع

Introduction

Organisational learning and economic geography

Knowledge linkages

Knowledge as a social phenomenon

Organisational learning and knowledge sourcing

Method and data

Two competitive firms in a thin region

Case analysis

Farsund aluminium casting

Organisational learning mechanisms

Interplay between technology and practice-based knowledge

Innovation capabilities

Knowledge linkages

Andersen Mekaniske Verksted

Organisational learning mechanisms

Interplay between technology and practice-based knowledge

Innovation capabilities

Knowledge linkages

Discussion

Concluding comments

References