دانلود رایگان مقاله وضعیت فعال سازی میکروگلی ها و سیستم کانبینوئید

چکیده

سلول های میکروگلی به عنوان سلول های ایمنی درون زاد مغز شناخته می شوند که فعالیت هایی نظیر محافظت سیستم ایمنی علیه شرایط مضر که تعادل CNS را تغییر می دهد تا کنترل تکثیر و تمایز نرون ها و آرایش سیناپتیک را کنترل می کنند. برای انجام این فعالیت ها، میکروگلی ها وضعیت فعالسازی مختلفی را تعدیل می کنند که به اصطلاح فنوتیپ نامیده می شود که به شرایط محیطی بستگی دارد که در شرایط التهابی نورون، ترمیم بافت و حتی رفع مشکلات التهابی نقش دارند. شواهد بسیاری در دسترس است که نشان می دهد کانابینوئیدها (CBs) ممکن است به عنوان یک ابزار امید بخش برای تغییر پیامده التهاب، خصوصا از طریق تحت تاثیر گذاشتن فعالیت میکروگلی ها عمل کند. میکروگلی دارای سیستم پیام رسانی عملکردی آندوکانابینوئید (eCB) هستند که از گیرنده های کانابینوئید و یک سیستم ماشینی کامل برای سنتز و تجزیه eCBs تشکیل شده است. بیان گیرنده های کانابیونوئید، اغلب CB2 و تولید eCBs به پروفایل این سلول ها ربط داده اند و بنابراین، فنوتیپ میکروگلی، به عنوان یک مکانیسم برای تغییر نوع و شیوه فعالسازی میکروگلی مطرح است. در اینجا، ما در مورد مطالعاتی که دیدگاه جدیدی در مورد نقش CBs و همتاهای درون زاد در تایین پروفایل فعالسازی میکروگلی بحث خواهیم کرد. این فعالیت، CBs را یک ابزار درمانی امید بخش برای جلوگیری از آثار مخرب التهاب می کند و احتمالا مسیر میکروگلی را برای ایجاد یک عامل ترمیمی در بیماری ها و اختلالات عصبی هموار تر کند.

1. مقدمه

میکروگلی ها بین 5 تا 20% کل سلول های گلیا را در جوندگان، بسته به منطقه سیستم عصب مرکزی (CNS) تشکیل می دهد و آنها اولین سلول هایی هستند که به شرایط مضر که باعث آسیب به عصب می شوند مانند عفونت و صدمه پاسخ می دهند. بنابراین، میکروگلی عمل محوری در حفظ سد خونی-مغزی است و در شرایط التهاب نورونی فعال می شوند تا هر نوع آسیب به CNS را تعدیل کند و ترمیم بافتی را بهبود بخشد. در حقیقت، اطلاعاتی وجود دارد که پیشنهاد می کند که میکروگلی می تواند تکثیر و تمایز نرورن ها و همچنین تشکیل سیناپس های جدید را در CNS کنترل کند. این ماهیت دوگانه به عنوان فاگوسیت تک هسته ای، علاقه برای شناسایی منشاء سلول های گلیال در CNS، و عملکرد آنها در شرایط سلامت و بیماری را افزایش داده است.

1.1. منشاء میکروگلی

خیلی قبل تر از معرفی واژه میکروگلی توسط del Río-Hortega در اوایل قرن 20، بحث های زیادی در مورد ماهیت و منشاء این سلول ها وجود داشته است. براساس این فرضیه که یک پیش ساز مشترک برای میکروگلی، آستروسیت و الیگودندورسیت وجود دارد، منشاء نورواکتودرم برای میکروگلی پیشنهاد شده است، نظریه ای که بعدها برای آن مدارک و دلایل بیشتری تهیه شد. بررسی پیش سازهای ولیه در مغز استخوان، وجود پیش سازهای موضعی مقاوم به تابش را پیشنهاد می کند که قبل از تولد در CNS حضور دارند و برخلاف سایر لوکوسیت های خون به تابش خیلی مقاوم بوده و توسط فرد اهدا کننده جایگزین نمی شود. در حقیقت، مطالعات اخیر پیشنهاد می کنند که تابش مغز با اشعه های یونیزان منجر به نفوذ سلول های ایمنی مشتق از مغز استخوان به CNS شامل ماکروفاژهای CCR2+ می شود.

منشاء مزودرمی براساس شواهد مورفولوژیک و ویژگی های فنوتیپی که بر روی تشابه بین میکروگلی و ماکروفاژ تمرکز دارد، انتخاب شده است. به عنوان مثال، میکروگلی توسط آنتی سرم های که با آنتی ژن های مونوسیت/ماکروفاژ تداخل دارد و هر دو سلول میکروگلی و ماکروفاژ مارکرهایی مانند CD11b، گیرنده Fc و F4/80 در موش بیان می کنند. مطالعات پیشقدم قادر بودند تا ماهیت میلوئیدی برای میکروگلی متصور شوند، چرا که موش های فاقد myeloid transcription factor Pu.1 عاری از سلول های میلوئید و میکروگلی بودند. شواهد بیشتر از این نظریه حمایت می کنند و بنابراین میکروگلی به عنوان فاگوسیت های تک هسته ای که شامل سلول های مشتق از مونوسیت، سلول های دندریتیک محیطی و ماکروفاژهای مرتبط با CNS قلمداد می شود.

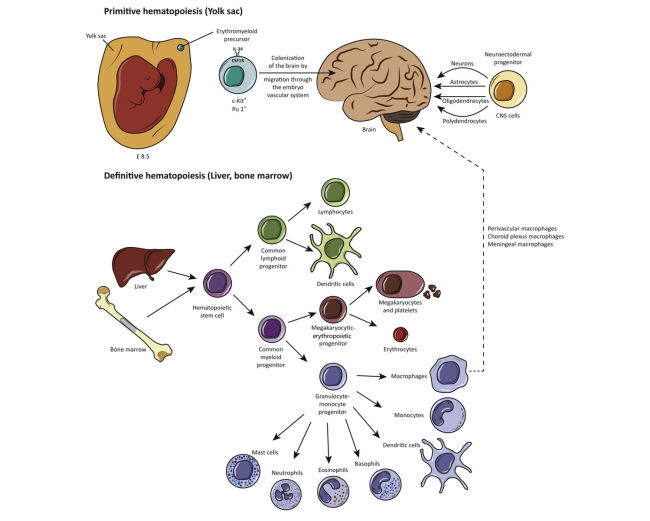

مطالعات Fate-mapping شواهدی را فراهم کرده اند که تحت شرایط متعادل، میکروگلیا از سلول های بنیادی خون ساز در کیسه زرده (YS) در طول رشد و توسعه جنین منشاء می گیرد. گرچه، گرچه جمعیتی از ماکروفاژهای مادرزادی بیان کننده CD45 در YS E7.5, یافت شده اند، این جمعیت سلولی به طور پیشرونده ای کاهش می یابند بطوری که در E9 قابل مشاهده نیستند، بنابراین می توان استنباط کرد که این سلول ها علیه عفونت های داخل رحمی نقش مراقبتی دارد. در موش، خونسازی اولیه اندکی پس از گاسترولیشن در YS آغاز می شود و قبل از اینکه سیستم گردش خون بین E8.5–E10 تکامل یابد. به طور جالبی، سلول های c-kit+ که برای شناساگر تقسیم سلول های خونساز بالغ منفی هستند در کیسه زرده اولیه پیدا شده اند، و این سلول ها می توانند به میکروگلی CX3CR1 و اریتروسیت های Ter119+ تمایز یابند، پیشنهاد کننده یک پیش ساز مشترک در کیسه زرده برای هر دو رده وجود دارد. پیش سازهای میکروگلی از جزیره خونی اطراف E9 منشاء می گیرند (شکل 1) و آنها از طریق سیستم عروقی رویان به مغز و سایر بافت ها مهاجرت می کنند و در آنجا به ماکروفاژهای جنینی تمایز می یابند. سلول های شبیه به ماکروفاژ به زودی E8.5/E9.0 در نوروآندوتلیوم در حال نمو با توانایی تمایز به ماکروفاژهای بیان کننده F4/80, Mac1 و Mac 3 قابل مشاهده هستند. در جنین، خونسازی نهایی از سلول های بنیاد خونساز مشتق از آئورت، گناد، و منطقه مزونفرون (AGM) پس از E8.5 منشاء خواهد گرفت. در حوالی E10.5، هر دو YS و پیش سازهای مشتق از AGM در کبد جنین کلنیزه خواهند شد که نشان دهنده ارگان اصلی خونسازی برای مونوسیت ها و شبکه کرونوئیدی اطراف عروقی و ماکروفاژهای مننژی است. نهایتا، پس از تولد سلول های میلوئید به طور ادامه دار در مغز استخوان از سلول های بنیادی خونساز ساخته می شوند (شکل1).

جمعیت میکروگلی ها پس از تولد افزایش یافته و تعداد میکروگلی های CD11b+F4/80+ تا 20 برابر بین P0 و P11 در جوندگان افزایش می یابد. در این خصوص، اخیرا نشان داده شده است که تخلیه وابسته میکروگلی توسط تاموکسیفن در موشهای دچار تغییر یافته ژنی صورت می پذیرد. با این وجود، برخی از سلول های مشتق از مغز استخوان می تواند به CNS نفوذ کنند و شکل و قابلیت فاگوسیتی میکروگلی غالبا در طول التهاب یا بیماری به دست آورند. در حقیقت، انتقال مغز استخوان در 24 ساعت اول تولد در موش های فاقد فاکتور رونوشت برداری Pu.1 می تواند به افزایش جمعیت میکروگلی پس از تولد کمک کند. در CNS بزرگسالان، مطالعات همبسته زیستی و تابشی نشان داده اند که تبدیل مونوسیت ها به میکروگلی بستگی به التهاب دارد و آن نیازمند شرایطی است که BBB را دچار اختلال می کند تا سلول های مشتق از مغز استخوان بتوانند به CNS وارد شوند. اخیرا یک بحث شدید به دنبال مشاهده افزایش مجدد جمعیت سلول های میکروگلی در مغز افراد بزرگسال در ظرفت مدت 1 تا 2 هفته توسط سلول هایی که به نظر مونوسیت های محیطی هستند به پا خواست، چرا که این سلول ها قادرند CD45 و CCR2 بیان کنند یا توسط پیش سازهایی که برای شناساگر نستین مثبت هستند. اینکه چگونه ای سلول های بیان کننده نستین پیش ساز میکروگلی در CNS هستند یا اگر آنها از مونوسیت های نفوذ کرده مشتق شده اند، باعث بحث و مشاجره بسیار زیادی بین محققین شده است.

1.2 فنوتیپ های میکروگلی: فعالسازی کلاسیک و جایگزین

منشاء رشد و نمو متمایز ماکروفاژها و میکروگلی از یکدیگر متمایز بوده، به همین دلیل ویژگی متمایزی نیز دارند که همواره مدنظر محققان بوده است. خصوصا در ارتباط با قطبیت میکروگلی و فنوتیپ های آن، این بحث و جدل بیشتر است. به طور سنتی، مفهوم فعال سازی کلاسیک یا جایگیزین ماکروفاژ برای میکروگلی، با توجه به انواع فنوتیپ های موجود در CNS که چه به طور کلاسیک فعال شده (M1-type) یا چه به طور جایگرین (M2-type) به کاربرده می شود. این نامگذاری دوگانه، نشان دهده فنوتیپ های وسیع تر با عملکردهای گوناگون ماکروفاژ و میکروگلی است به طوری که M1 در ارتباط با فعالیت های سیتوتوکسیک، M2 با ترمیم و بازسازی (subtype M2a)، تعدیل سیستم ایمنی (M2b) یا فعالسازی اکتسابی (M2c) در ارتباط است. انواع فنوتیپ های مطرح شده، شناساگرها و ویژگی های مربوطه در شکل 2 خلاصه شده است.

گرچه سیگنالهایی که قطبیت فنوتیپ M1 و M2 تعدیل می کنند به طور برون تنی قابل شناسایی هستند، مطالعات درون تنی نشان داد که محیط اطرافی مغز می تواند به طور همزمان M1 و M2 را پلاریزه کند، بنابراین پاسخ میکروگلی می تواند به تناسب بین فنوتیپ ها بستگی داشته باشد. چندین سیگنال که از ماکروفاژ و میکروگلی منشاء می گیرد و منجر به انواع فعالسازی می گردد تا کنون شناسایی شده است و از آنجایی این عمل پاسخ سیستم ایمنی ذاتی را برمی انگیزد، سیتوکاین های مشتق از لنفوسیت T نیز بین آنها قرار دارد. در انسان، نشان داده شده است که لنفوسیت های T جداشده از بیماران مبتلا به MS و Th1 یا Th2 پلاریزه در محیط برون تنی باعث تمایز مونوسیت ها و میکروگلی ها به سلول های عرضه کننده آنتی ژن (APC) M1 یا M2 می شود. در موش، فنوتیپ M1 هر دو سلول ماکروفاژ و میکروگلی به طور مرسومی با سیتوکاین اینترفرون گاما Th1 و لیپوپلی ساکارید باکتریایی (LPS) درحالی فنوتیپ M2a از سیتوکاین اینترلوکین 4 (IL-4) و 13 (IL-13) مشتق می شود. سایر القاء کننده های اصلی آگونیست های گیرنده های شبیه Toll (TLR)، کمپلکس های سیستم ایمنی و لیگاندهای IL-1R برای M2b، یا گلوکوکورتیکوئید، IL-10 و فاکتور رشد بتا (TGF-β) برای M2c است.

در حالت ثابت، سلول های میکروگلی یک بدنه کوچک با شاخه های متعدد دارند و وضعیت مرفولوژی آنها بسته به وضعیت فعالسازی آنها فرق می کند. واژه میکروگلی resting (در حال استراحت) برای میکروگلی موجود در CNS سالم به کارفته می شود که درحالی بررسی محیط و بافت عصبی هستی، به طور که کل بافت مغز در ظرف 5 ساعت به طور کامل بررسی می شود. ترشح فاکتورهای نوروتوپیک توسط میاروگلی ها مانند فاکتور رشد عصب (NGF)، TGF-β، فاکتور رشد انسولین1 (IGF-1) یا فاکتور نوروتوپیک مشتق از مغز (BDNF)، در شرایط پاتولوژیک نشن داده شده اند که به بازیابی تعادل محیط عصبی کمک می کنند. پاسخ میکروگلی برای آرایش صحیح سیناپسی، فاگوسیتوز نوروبلاست های آپوپتوتیک در گیروس های مضرس هیپوکمپ های در حال رشد و برای فرآیندهایی مانند نوروژنز در مغز بالغ یا هدایت سلول های بنیادی به موضع التهاب و آسیب لازم است. حفظ نظارت بر فنوتیپ میکروگلی بستگی به تماس سلول-سلول با نورون ها، شامل سیگنالینگ در طول میکروگلی CX3CR1, CD172 یا گیرنده های CD200R که CX3CL1 میانکنش برقرار می کنند، و انواع دیگر پیام ها دارد. بعلاوه، مولکول های محلول چسبنده، مهار کننده های neurotransmission، سایتوکاین های مهاری و گیرنده هایشان می توانند به اثرات مهاری محیط برای حفظ ثبات میکروگلی دخالت نمایند.

Abstract

Microglial cells are recognized as the brain's intrinsic immune cells, mediating actions that range from the protection against harmful conditions that modify CNS homeostasis, to the control of proliferation and differentiation of neurons and their synaptic pruning. To perform these functions, microglia adopts different activation states, the so-called phenotypes that depending on the local environment involve them in neuroinflammation, tissue repair and even the resolution of the inflammatory process. There is accumulating evidence indicating that cannabinoids (CBs) might serve as a promising tool to modify the outcome of inflammation, especially by influencing microglial activity. Microglia has a functional endocannabinoid (eCB) signaling system, composed of cannabinoid receptors and the complete machinery for the synthesis and degradation of eCBs. The expression of cannabinoid receptors – mainly CB2 – and the production of eCBs have been related to the activation profile of these cells and therefore, the microglial phenotype, emerging as one of the mechanisms by which microglia becomes alternatively activated. Here, we will discuss recent studies that provide new insights into the role of CBs and their endogenous counterparts in defining the profile of microglia activation. These actions make CBs a promising therapeutic tool to avoid the detrimental effects of inflammation and possibly paving the way to target microglia in order to generate a reparative milieu in neurodegenerative diseases.

1. Introduction

Microglia represents between 5–20% of total glial cells in rodents, depending on the specific central nervous system (CNS) region (Lawson et al., 1990), and they are the primary cells that respond to potentially harmful conditions that could lead to neuronal loss, like injury or infection. Thus, microglia is the central custodians acting under the protection of the blood–brain barrier (BBB: Daneman, 2012) and is activated in neuroinflammatory conditions to moderate any potential damage to the CNS and to favor tissue repair. Indeed, data has emerged to suggest that microglia can control proliferation and differentiation of neurons, as well as the formation of new synapses in the healthy CNS (Graeber, 2010; Hughes, 2012). This dual nature as a mononuclear phagocyte and a glial cell of the CNS expands the interest in microglial ontogeny, origin, development and function in health and disease.

1.1. The origin of microglia

Long before the introduction of the term “microglia” by del Río-Hortega early in the 20th century (del Río-Hortega, 1932), there had been much discussion about the nature and the origin of these cells. Two schools of thought developed at the same time supporting both the ectodermal or mesodermal origin of microglia. The neuroectodermal origin was suggested based on the supposition that a common progenitor existed for microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Fujita & Kitamura, 1975; Kitamura et al., 1984), a theory for which further support gathered (Hao et al., 1991; Fedoroff et al., 1997). Pioneer bone marrow chimera experiments suggested the existence of radiation-resistant local precursors that are present in the CNS prior to birth, and showed that microglia is highly resistant to radiation in contrast to other blood leukocyte populations and cannot be replaced by donor cells (Lassmann et al., 1993; Priller et al., 2001). Indeed, recent studies suggest that brain irradiation per se results in the infiltration of bone marrow derived immune cells into the CNS (Moravan et al., 2016), including CCR2+ macrophages (Morganti et al., 2014).

The mesodermal origin was based on morphological evidence and phenotypic features that focused on the resemblance between microglia and macrophages. For example, microglia is recognized by antisera that interact with monocyte/macrophage antigens (Hume et al., 1983; Murabe & Sano, 1983), and both microglia and macrophages express markers like CD11b, the Fc receptor and F4/80 in mouse (Perry et al., 1985; Akiyama & McGeer, 1990). Pioneering studies were eventually able to establish the myeloid nature of microglia, since mice lacking the myeloid transcription factor Pu.1 were devoid of myeloid cells and microglia (McKercher et al., 1996). Further evidence supported this hypothesis (Herbomel et al., 2001; Beers et al., 2006; Schulz et al., 2012) and therefore microglia is classified as mononuclear phagocytes that include monocyte-derived cells, dendritic cells, peripheral and CNS-associated macrophages (Prinz et al., 2011; Gomez Perdiguero et al., 2013).

Fate-mapping studies provided evidence that under homeostatic conditions, microglia originates from hematopoietic stem cells in the yolk sac (YS) during early embryogenesis (Ginhoux et al., 2010; Schulz et al., 2012; Kierdorf et al., 2013). Although a population of maternally derived committed CD45 expressing macrophages has been found in the YS at E7.5, this population progressively declines and is no longer detected at E9. Thus, it is believed that these cells could have a restrictive protective effect against intrauterine infections in the embryo (Bertrand et al., 2005). In mice, primitive hematopoiesis initiates in the YS shortly after the onset of gastrulation at E7, and before the circulatory system becomes fully established between E8.5–E10 (reviewed in Ginhoux et al., 2013). Interestingly, c-kit+ cells that are negative for lineage markers of mature hematopoietic cell progenitors have been found in the early YS, and these cells can differentiate into CX3CR1 microglia and Ter119+ erythrocytes, suggesting a common progenitor in the YS for both lineages (Kierdorf et al., 2013). Microglia progenitors arise in the blood islands of the YS around E9 (Fig. 1), and they migrate through the embryo vascular system to the brain and other tissues were they differentiate into “fetal” macrophages (Naito et al., 1990). Macrophage-like cells can be found in the developing neuroepithelium as early as E8.5/E9.0, with the capacity to differentiate in vitro into microglia-like cells that express markers like F4/80, Mac1 and Mac 3 (Alliot et al., 1991). In the embryo, definitive hematopoiesis will be established from hematopoietic stem cells generated in the aorta, gonads and mesonephros (AGM) region after E8.5 (Orkin & Zon, 2008). At around E10.5, both YS and AGM-derived hematopoietic precursors will colonize the fetal liver, which represents the major hematopoietic organ for monocytes and potentially perivascular, choroid plexus and meningeal macrophages (Kumaravelu et al., 2002). Finally, after birth myeloid cells are continuously produced in the bone marrow (Fig. 1) from hematopoietic stem cells (Prinz & Priller, 2014).

The microglia population expands after birth, and the number of CD11b+F4/80+ microglia increases 20-fold between P0 and P11 in rodents by a mechanism that does not seem to involve the recruitment of peripheral myeloid cells (Ginhoux et al., 2010; Schulz et al., 2012). In this line, it has been recently demonstrated that time-controlled microglia depletion induced by tamoxifen in genetically modified mice is renewed by an internal pool, demonstrating the renovation capability of microglia without peripheral myeloid contribution (Bruttger et al., 2015). However, some bone-marrow-derived cells can infiltrate into the CNS, and assume the morphology and phagocytic capacity of microglia, mainly during inflammation or disease. Indeed, bone marrow transplants within 24 h of birth in the transcription factor Pu.1 knockout mice show that bone marrow-derived cells can contribute to the postnatal microglia population as they drive the de novo generation of these cells in this situation (Beers et al., 2006). In the adult CNS, irradiation and parabiosis studies have demonstrated that the contribution of monocytes to microglia population depends on inflammation and it requires conditions that would probably disrupt the BBB to allow bone-marrow derived cells to enter the CNS (Ajami et al., 2007; Mildner et al., 2007). A strong debate has recently arisen after it was seen that the adult brain is repopulated within 1–2 weeks after microglia depletion by cells that are assumed to be peripheral monocytes since they express CD45 and CCR2 (Varvel et al., 2012), or by local progenitors positive for the neuronal marker nestin (Elmore et al., 2014). It remains controversial as to whether these nestin expressing cells are microglial progenitors in the CNS or if they are derived from infiltrating monocytes, reopening the debate as to the origin of microglia in homeostatic conditions and disease, an issue that will hopefully be clarified in the next few years.

1.2. Microglia phenotypes: classical and alternative activation

Given the distinct developmental origin of macrophages and microglia, the different features of these two cells have begun to be considered, particularly in terms of the nomenclature and concept of microglial phenotype polarization. Traditionally, the concept of classic or alternative macrophage activation has been applied to microglia, considering the different CNS phenotypes as either the classically activated (M1-type) or the alternatively activated state (M2-type). This dichotomic nomenclature overlooks the richer spectrum of phenotypes related to functions of macrophages and microglia, associating M1 with cytotoxic properties and M2 with regeneration and repair (subtype M2a), immunoregulation (M2b) or an acquired-deactivating phenotype (M2c) (Martinez et al., 2009). The proposed phenotypes, inductors and markers for microglia are summarized in Fig. 2. Although the signals that control the polarization of M1 and M2 phenotypes can be determined in vitro (Chorr et al., 2013), in vivo studies show that the local environment of the brain can simultaneously supply M1 and M2 polarizing cues (Martinez & Gordon, 2014). Thus, the microglia response could depend on the ratios between a range of phenotypes.

Several of the signals that drive macrophages and microglia into the different activation states have been defined, and since this enables the adaptive response of innate immunity to take place, cytokines derived from T lymphocytes are among the signals implicated in the polarization of these cells. In humans, it has been shown that T lymphocytes isolated from patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) and polarized to Th1 or Th2 cells in vitro, differentially modulate human monocytes and microglia to an M1 or M2 antigen-presenting cell (APC), respectively (Kim et al., 2004). In mice, the M1 phenotype of both macrophages and microglia has typically been associated with Th1 cytokine interferon gamma (IFNγ) and bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), whereas the M2a phenotype is driven by the Th2 cytokines Interleukin 4 (IL-4) and 13 (IL-13) (Prinz & Priller, 2014). Other prototypic inducers are Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, immune complexes and IL-1R ligands for M2b, or glucocorticoids, IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) for M2c (Schmid et al., 2009).

In the steady state, microglial cells have a small soma and ramifications with non-overlapping processes, and they have distinct morphological features depending on their state of activation. The term “resting” microglia has been updated in the healthy CNS to “surveillant”, as they continuously monitor the nervous tissue and palpate the environment, such that the entire brain volume is examined in approximately 5 h, as suggested by two-photon studies in vivo (Nimmerjahn et al., 2005). The secretion of neurotrophic factors by microglia like nerve growth factor (NGF), TGF-β, insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) or brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) has been demonstrated in pathological conditions, contributing to the restoration of homeostasis (Bessis et al., 2007; Polazzi & Monti, 2010). Microglia responses are thought to be required for synaptic pruning (Paolicelli et al., 2011), phagocytosis of apoptotic neuroblasts in the dentate gyrus of the developing hippocampus (Sierra et al., 2010), and for processes like neurogenesis in the mature brain (Walton et al., 2006) or the guidance of stem cells in their migration to sites of inflammation and injury (Aarum et al., 2003). Maintaining the microglia surveillance phenotype depends on cell–cell contact with neurons, including signaling through microglial CX3CR1, CD172 or CD200R receptors upon interaction with secreted CX3CL1 by neurons, or the neuronal CD47 and CD200 proteins, respectively. In addition, soluble adhesion molecules, neurotransmission-associated inhibitors, inhibitory cytokines and their receptors can also contribute to the microenvironment's inhibitory influences for restraining microglia activation (reviewed by Ransohoff & Cardona, 2010).

چکیده

1. مقدمه

1.1. منشاء میکروگلی

1.2 فنوتیپ های میکروگلی: فعالسازی کلاسیک و جایگزین

1.3 التهاب حاد در سیستم عصبی مرکزی

1.4 التهاب مزمن در سیستم عصبی مرکزی: چشم انداز فنوتیپ M2 ≥ M1 برای ارتقاء ترمیم بافتی

1.4.1 بیماری آلزایمر

1.4.2 بیماری پارکینسون

1.4.3 مالتیپل اسکلروزیس

2. سیستم های کانابینوئید

2.1 چشم انداز: لیگاندها و گیرنده های سیستم آندوکانابینوئید

2.2. کانابینوئیدها و التهاب: تعدیل ایمنی

2.3. میکروگلی و سیستم کانابینوئید

2.4 میکروگلی آندوکانابینوئیدها را سنتز می کنند

2.5. آندوکانابینوئیدها اکتساب فنوتیپ جایگزین را در میکروگلی به عهده می گیرد

3. هدف قرار دادن میکروگلی: مسائل درمانی کانابینوئید در التهاب نرونی

4. خلاصه و نتیجه گیری

منابع

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The origin of microglia

1.2. Microglia phenotypes: classical and alternative activation

1.3. Acute inflammation in the central nervous system

1.4. Chronic inflammation in the central nervous system: the perspective of the M2 N M1 phenotype to promote regeneration

1.4.1. Alzheimer's disease

1.4.2. Parkinson's disease

1.4.3. Multiple sclerosis

2. Cannabinoid system

2.1. Overview: ligands and receptors of the endocannabinoid system

2.2. Cannabinoids and inflammation: immune modulation

2.3. Microglia and cannabinoid system

2.4. Microglia synthesizes endocannabinoids

2.5. Endocannabinoids drive the acquisition of alternative phenotype in microglia

3. Targeting microglia: therapeutic implications of cannabinoids in neuroinflammation

4. Summary and conclusions

References