دانلود رایگان مقاله رهبری پروژه و دستور کار تحقیقاتی

چکیده

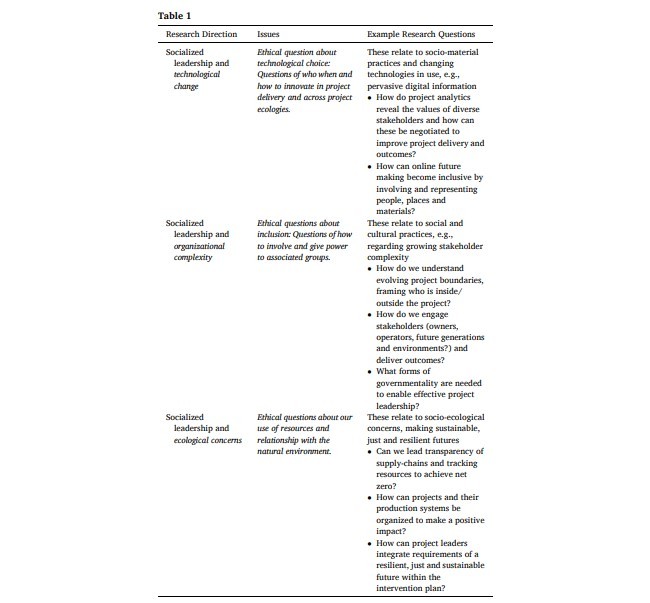

رهبری پروژه به طور فزاینده ای در زمینه خطرات زیست محیطی رخ می دهد، چه ناشی از یک بیماری همه گیر ویروسی یا یک آب و هوای انسانی در حال تغییر. این نیاز به سازگاری برای تغییر دارد، به ویژه هنگامی که پروژه ها در پیچیدگی رشد می کنند و به عنوان مداخلات در سیستم های گسترده تر دیده می شوند. در این مقاله، ما یک دیدگاه اجتماعی را در نظر می گیریم، کار اخیر را ترکیب می کنیم و یک دستور کار تحقیقاتی جدید را در سه حوزه مرتبط به هم پیشنهاد می کنیم که باید توسط رهبری پروژه مورد توجه قرار گیرد: 1) تغییر فناوری ها، باز کردن ارزش هایی که فناوری ها برای دستیابی به نتایج مطلوب نشان می دهند. 2) پیچیدگی سازمانی، درگیر کردن بازیگران متعدد و پرداختن به پیچیدگی ها و عدم قطعیت های در حال ظهور و 3)، نگرانی های زیست محیطی، رسیدگی به خواسته ها برای پروژه ها برای مداخله مثبت برای ایجاد آینده های پایدار، انعطاف پذیر و عادلانه. سهم ما تئوریزه کردن معنای رهبری اجتماعی شده برای این موضوعات حیاتی است که در مطالعات پروژه ظهور میکنند و دستورالعملهایی را برای تحقیقات بیشتر در مورد اشکال مثبت رهبری پروژه در جهانی در حال تغییر تعیین میکنیم.

1. مقدمه

پروژه ها اشکال آینده نگر سازماندهی هستند (نایتینگل و همکاران، 2011؛ وایت و همکاران، 2022). آنها در دنیای پیچیده سازمانی ما برای دستیابی به اهداف مورد نظر استفاده می شوند. به عنوان مثال، برای مدیریت واکنش و بازیابی در مواجهه با بلایا (چانگ-ریچاردز و همکاران، 2017). برای طراحی و تحویل واکسن (تیفای و همکاران، 2015)؛ پیکربندی مجدد ماهیت مدنیت در روابط اجتماعی (پارتیس-جنیگز، 2017). برای نجات گونه های در معرض خطر (Willemsen et al., 2020)؛ برای مقاوم سازی و نگهداری محیطهای ساخته شده (تئو و همکاران، 2021)، و همچنین سازگاری حمل و نقل و ارائه زیرساختهای جدید (دیویس و همکاران، 2019). پروژهها (و نمونه کارها و برنامههای مرتبط) گسترده هستند، با برخی از محققان که «طرحنمایی» یا «برنامهریزی» جامعه را توصیف میکنند (مانند مایلور و همکاران، 2006؛ جنسن و همکاران، 2016؛ شوپر و اینگاسون، 2019). دستیابی به نتایج مطلوب و مطلوب از طریق پروژه ها مستلزم تصمیم گیری اخلاقی است (Helgadottir, ´ 2008)، به خصوص که جوامع با خطرات زیست محیطی مواجه هستند، چه ناشی از یک بیماری همه گیر ویروسی یا یک آب و هوای در حال تغییر انسانی.

در زمینه دنیای در حال تغییری که ما در آن زندگی می کنیم، کار بر روی پروژه ها، آینده ممکن، احتمالی و ترجیحی جدیدی را به نمایش می گذارد (Tutton, 2017). با اینها، چالش های جدیدی به وجود می آید. اگرچه بسیاری از تکنیک ها برای مدیریت پروژه های بزرگ ریشه در پروژه های اواسط قرن بیستم دارند (موریس، 2013؛ دیویس، 2017)، سازمان دهی پروژه ها با تبدیل شدن پروژه ها به عنوان مداخلات در حال تحول است (وایت و همکاران، 2019) که نتایج را در زمینه ارائه میکنند. زمینه های فناوری، اجتماعی و زیست محیطی گسترده تر. پویایی در چندین سیستم و سطوح منجر به اختلال می شود. رهبری پروژه به طور فزاینده ای نیاز به توجه به سیستم های در حال تغییر فناوری ها، تعدد سهامداران، افزایش پیچیدگی و پویایی سازمانی، همه در چارچوب چالش های پایداری و انعطاف پذیری دارد. بنابراین، ما استدلال میکنیم که پروژههای معاصر و آینده بیش از کاربرد روشهای استاندارد پروژه برای کارهای آشنا نیاز دارند. آنها به اشکال جدیدی از رهبری پروژه نیاز دارند که سرمایه اجتماعی را ایجاد می کند که تحول آفرین باشد، دربرگیرنده نحوه برخورد با پیچیدگی و همچنین پایدار باشد. ما از این به عنوان «رهبری اجتماعی» یاد می کنیم. رهبری پروژهها نه تنها با تکمیل پروژه بر اساس بودجه، بر اساس زمانبندی و محدوده، بلکه با تعهد به ارزشها و اهداف مبتنی بر گستردهتر در پروژهها هماهنگ است (کلگ و همکاران، 2021). این نیاز به سازگاری برای تغییر دارد، به ویژه هنگامی که پروژه ها در پیچیدگی رشد می کنند (کوک دیویس و همکاران، 2007؛ رمینگتون و پولاک، 2008)، که به عنوان مداخله در سیستم های گسترده تر شناخته می شود.

کار ما به طور انتقادی به بررسی مواردی میپردازد که به عنوان سؤالات فوری برای تعیین رهبری پروژه در محیط فرار، نامطمئن، پیچیده و مبهم امروزی شناسایی شدهاند (Drouin و همکاران 2018، 2021؛ Floris and Cuganesan، 2019). تا همین اواخر، ادبیات مدیریت پروژه عمدتاً بر مدیر پروژه بهعنوان «رهبر» متمرکز بود، اصطلاحی که در دوران نئولیبرال در محافل تجاری و مدیریتی مورد تحسین قرار گرفت (Learmonth and Morrell 2021). درک روزافزونی وجود دارد که رهبری منحصراً به رفتار یک فرد مربوط نمیشود، بلکه رابطهای و بهطور پیوندی تیم محور است (مولر و همکاران 2018)، که به طور بالقوه اشکال تقسیمی و سازمانی را در بر میگیرد. چنین شناختی با تغییرات متعدد در درک سازماندهی، قدرت و رهبری پیش بینی شده است.

تغییری در عمل به شکلهای کمتر سلسله مراتبی و سازگارتر سازماندهی صورت گرفته است (مک کریستال و همکاران، 2015) که در آن شایستگیهای فردی و فنی برجستگی خود را حفظ میکنند (Bolzan de Rezende و همکاران، 2021) اما این کار را در زمینههای بیشتر انجام میدهند. روابط توزیع شده به عنوان مثال، در تفکر نظامی، سنگر مدلهای فرماندهی و کنترل قدیمی، تمرکز بر مفهومی از قدرت است که نه تنها به عنوان فرماندهی و سلسله مراتب با اعمال «غلبه» مفهومسازی شده است، بلکه «قدرت به» و «قدرت با» را نیز در بر میگیرد. با تأکید بر چیزی که آرنت (1972) به عنوان «ظرفیت کنسرت کنسرت» از آن یاد کرد (ر.ک. انگستروم و هالدن، 2019). تغییر در تفکر، بینش استراتژیک برای رهبری پروژه را قادر می سازد که از کار اخیر در مورد قدرت به دست آید (به عنوان مثال Haugaard، 2020). در گذشته، رهبری پروژه معمولاً برای ارائه پروژهها با استقرار فرمان ضروری، با استفاده از «قدرت بر» تلاش میکرده باشد، اما به طور فزایندهای از «قدرت به» با توانمندسازی بازیگران پروژه و ایجاد همکاریهای جدید با فرض تقسیم «قدرت» با حوزههایی که قبلاً به حاشیه رانده شدهاند، استفاده میکند. مورد علاقه. اینها تفاوت هایی در مقیاس هستند که مهم هستند. حرکت از «قدرت بر» به «قدرت به» و «قدرت با» با دور شدن از درک رهبری بهعنوان مدیریت مستبد به تأکید بر توانمندسازی تیمهای پروژه برای عمل مؤثر همراه است (آگا و همکاران، 2016؛ دینگ و همکاران. ، 2017؛ وو و همکاران، 2017؛ لای و همکاران، 2018)، امکان فعالیت در یک محیط پیچیده سازمانی، با سهامداران متعدد را فراهم می کند.

این تغییرات درک ساده ارزش را مشکل ساز می کند و ذینفعان پروژه و ارزش های متنوع و بالقوه ناسازگار آنها را در معرض دید قرار می دهد. جایی که همه احزاب در یک سیستم اجتماعی باثبات عمل می کنند، ارزش ممکن است نسبتاً بدون مشکل باشد. با این حال، در دنیایی که به سرعت در حال تغییر است، ارزش را می توان به طرق مختلف برای گروه های مختلف بازیگران تعریف کرد. دستیابی به چنین مفاهیم گستردهتری از ارزش دشوار است زیرا عدم قطعیت، ابهام، پیچیدگی و از همه چالشبرانگیزتر، رویدادها میتوانند ارزش را منحرف، بیثبات یا تخریب کنند (کلگ و همکاران، 2021). تعدد مجموعه های مختلف دانش زیربنایی، مفروضات و رویه ها برای ارزیابی ارزش (بولتانسکی و تیونوت، 2006 [1991])، منجر به تنش و پویایی بین رژیم های ارزشی می شود (لوی و همکاران، 2016). در این زمینه، رهبری پروژه شامل ایجاد توافق قابل توجیه، چه از طریق هدف مشترک یا از طریق آتشبس و مصالحه محلی، پر از قضاوت موقعیتی (بولتانسکی و تیونوت، 2000) است که برای ایجاد نتایجی که توسط بسیاری از بازیگران مختلف، از جمله آینده، ارزش قائل است، تلاش میکند.

در این مقاله، ما با در نظر گرفتن رهبری پروژه در چارچوب رویکردهای رهبری معاصر و تعیین یک دستور کار تحقیقاتی برای رهبری پروژه در دنیای در حال تغییر، مشارکتی نظری داریم. ما این کار را با ایجاد مسیرهای کاری انجام میدهیم که از پروژههای مجزا، مدیریت سلسله مراتبی و استفاده از روشهای استاندارد پروژه برای کارهای آشنا فاصله میگیرد. در عوض، ما اشکال مشترک، توزیع شده و مشارکتی رهبری را توضیح می دهیم که برای تغییر جهان به سوی بهتر مورد نیاز است. دیدگاه اجتماعی، رهبری را مجموعهای از شیوههای توزیع شده میبیند که در یک جریان اجتماعی مستمر اعمال میشوند (کروانی و همکاران، 2010). ساختار اجتماعی رهبری را به رسمیت می شناسد و به آن توجه می کند، تخصص فنی از قبل موجود و تعریف نقش را برای رهبری پروژه در زمینه های پویا در حال تغییر که پروژه های معاصر مداخله می کنند بسیار مهم و ناکافی می داند. نیاز به توجه بیشتر به سه حوزه دگرگونی مرتبط با یکدیگر وجود دارد: تغییر فناوریها، که در آن انتخابهای مرتبط بعد اخلاقی دارند، درگیر شدن با ارزشهای متعدد. پیچیدگی سازمانی رو به رشد با بازیگران متعدد و پیچیدگی و عدم قطعیت در حال ظهور، همراه با تقاضا برای پروژهها برای مداخله مثبت برای ایجاد آیندهای پایدار، انعطافپذیر و عادلانه. این انتقال در این سه حوزه است که مرزهای اطراف پروژه ها را بر هم می زند و اصلاح می کند، سؤالاتی را در مورد رژیم های ارزشی و رهبری آنها ایجاد می کند، فرصت های جدیدی را برای رهبری ایجاد می کند که تنوع دانش را هماهنگ می کند و به آن ارزش می دهد.

در بخش بعدی، با تشریح مواردی که از نظر ما برای رهبری پروژه در زمینه معاصر است، شروع می کنیم. در بخش بعدی، بینشهای پژوهشی و جهتگیریها را برای تحقیقات بیشتر مرتبط با این سه انتقال ترسیم میکنیم، و بیان میکنیم که چگونه پروژهها به عنوان مداخلات، شکلگرفته از زمینههای فناوری، اجتماعی و زیستمحیطی گستردهتر، نیاز به رهبری از طریق اشکال جدید تعامل و همکاری دارند. طیفی از بازیگران ما سؤالات احتمالی تحقیقات آینده را که می تواند به بینش بیشتر منجر شود، بحث می کنیم و با خلاصه کردن سهم و پیشنهاد گام های بعدی برای تحقیقات آینده، نتیجه گیری می کنیم.

2. رهبری پروژه در چارچوب رهبری معاصر نزدیک می شود

در ادبیات رهبری پروژه، خط سیر قابل توجهی از تحقیقات وجود دارد که بر رهبر به عنوان فردی با ویژگیهای خاص متمرکز است (مانند Zaccaro and Day، 2014؛ Merrow and Nandurdikar، 2018؛ Zhang و همکاران، 2018). با این حال، ما استدلال میکنیم که مطالعه رهبری پروژه نمیتواند محدود به مطالعه «رهبر»، به عنوان یک فرد، با تیپ شخصیتی، سبک رهبری یا مسیر شغلی شخصی باشد. رهبری در شیوه ها و تعاملاتی اعمال می شود (کروانی و همکاران، 2010) که در بین پروژه های بین سازمانی و زمینه هایی که در آن ارائه می شود توزیع می شود. در دنیای در حال تغییر ما، جایی که زمینه های پروژه در جریان است، آنها در چارچوب فناوری های در حال تغییر ارائه می شوند، با دیجیتالی شدن تحویل و محصولات قابل تحویل چالش های جدیدی را ارائه می دهند. پویایی سازمانی، با افزایش پیچیدگی ذینفعان همراه با فراگیری بیشتر علایق؛ و نگرانی های زیست محیطی، با برجستگی پرسش های پایداری و تاب آوری..

ABSTRACT

Project leadership increasingly occurs in the context of ecological risks, whether from a viral pandemic or an anthropogenically changing climate. It requires adaptability to change, especially as projects grow in complexity, becoming seen as interventions into wider systems. In this paper, we take a socialized perspective, synthesising recent work and proposing a new research agenda in three inter-related areas that need to be addressed by project leadership: 1) changing technologies, unpacking the values that technologies represent to achieve desirable outcomes; 2) organizational complexity, engaging multiple actors and addressing emerging complexity and uncertainty and 3), ecological concerns, addressing the demands for projects to intervene positively to create sustainable, resilient and just futures. Our contribution is to theorize what socialized leadership means for these crucial issues emerging in project studies and set out directions for further research on positive forms of project leadership in a changing world.

1. Introduction

Projects are future-oriented forms of organizing (Nightingale et al., 2011; Whyte et al., 2022). They are used in our complex organizational world to achieve desired ends; for example, to manage response and recovery in the face of disasters (Chang-Richards et al., 2017); to design and deliver vaccines (Tiffay et al., 2015); to reconfigure the nature of civility in social relations (Partis-Jennings, 2017); to save endangered species (Willemsen et al., 2020); to retrofit and maintain built environments (Teo et al., 2021), as well as to adapt transport and deliver new infrastructure (Davies et al., 2019). Projects (and the associated portfolios and programs) are widespread, with some scholars describing the ‘projectification’ or ‘programification’ of society (e.g. Maylor et al., 2006; Jensen et al., 2016; Schoper and Ingason, 2019). Achieving desired and desirable outcomes through projects requires ethical decision-making (Helgadottir, 2008 ´ ), especially as societies face ecological risks, whether from a viral pandemic or an anthropogenically changing climate.

In the context of the changing world we inhabit, work on projects brings into view new possible, probable and preferred futures (Tutton, 2017); with these, new challenges arise. Although many techniques for managing major projects have their origins in mid-20th century projects (Morris, 2013; Davies, 2017), project organizing is transforming as projects become seen as interventions (Whyte et al., 2019) delivering outcomes in the context of wider technological, societal and ecological contexts. The dynamics across multiple systems and levels lead to disruptions. Project leadership will increasingly need to attend to changing systems of technologies, a multiplicity of stakeholders, increased organizational complexity and dynamics, all in the context of the challenges of sustainability and resilience. Thus, we argue that contemporary and future projects will demand more than the application of standard project methodologies to familiar tasks; they will require novel forms of project leadership that builds social capital that is transformational, inclusive in how it deals with complexity, as well as sustainable. We refer to this as ‘socialized leadership’; leadership of projects attuned not just to project completion on budget, on schedule and scope but also to a commitment to broader based values and purpose in projects (Clegg et al., 2021). It requires adaptability to change, especially as projects grow in complexity (Cooke-Davies et al., 2007; Remington and Pollack, 2008), becoming understood as interventions into wider systems.

Our work critically examines what have been identified as urgent questions for delineating project leadership in today’s volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment (Drouin et al. 2018, 2021; Floris and Cuganesan, 2019). Until recently, the project management literature has largely focused on the project manager as ‘leader’, a term that has been subject to some aggrandisement in business and management circles and writing during the neoliberal era (Learmonth and Morrell 2021). There is increasing recognition that leadership is not exclusively related to the behaviour of an individual but is relational and connectively team-centred (Müller et al. 2018), potentially spanning divisional and organizational forms. Such recognition is predicated on several shifts in understanding of organizing, power and leadership.

There has been a shift in practice to less hierarchical, more adaptive forms of organizing (McChrystal et al., 2015) in which individual and technical competences retain salience (Bolzan de Rezende et al., 2021) but do so in the context of more distributed relations. For example, in military thinking, the bastion of the old command and control models, the focus has been shifting to a notion of power not only conceptualized as command and hierarchy exercising ‘power over’ but also incorporating ‘power to’ and ‘power with’, stressing what Arendt (1972) referred to as ‘the capacity to act in concert’ (cf. Angstrom and Hald´en, 2019). The shift in thinking enables strategic insight for project leadership to be gained from recent work on power (e.g. Haugaard, 2020). In the past, project leadership may normally have striven to deliver projects by deploying imperative command, using ‘power over’ but increasingly it is using ‘power to’ by empowering project actors and forging new collaborations premised on sharing ‘power with’ previously marginalized constituencies of interest. These are differences in scale that matter; moving from ‘power over’ to ‘power to’ and ‘power with’ is accompanied by a shift away from understanding leadership as authoritarian management to a stress on enabling project teams to act effectively (Aga et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2017; Lai et al., 2018), enabling activity across a complex organizational setting, with multiple stakeholders.

These shifts problematize simple understandings of value, bringing into view project stakeholders and their diverse and potentially incompatible values. Where all parties operate in a stable social system, value may be relatively unproblematic; in the rapidly changing world, however, value can be defined in many ways, for many different categories of actors. Such broader-based conceptions of value are hard to achieve because uncertainty, ambiguity, complexity and most challengingly, events, can distract, destabilize or destroy value (Clegg et al., 2021). The multiplicity of different underlying knowledge sets, assumptions and procedures for evaluating worth (Boltanski and Th´evenot, 2006 [1991]), lead to tensions and dynamics between value regimes (Levy et al., 2016). In this context, project leadership involves creating justifiable agreement, either through shared purpose or through local truces and compromises, full of situated judgement (Boltanski and Th´evenot, 2000) working to create outcomes that are valued by many diverse actors, including future as well as current generations.

In this paper, we make a theoretical contribution by considering project leadership in the context of contemporary leadership approaches and setting out a research agenda for project leadership in a changing world. We do this by building on trajectories of work that move away from isolated projects, hierarchical management and the application of standard project methodologies to familiar tasks. Instead, we explicate shared, distributed and participatory forms of leadership that are required to change the world for the better. A socialized perspective sees leadership as a distributed set of practices, enacted in a continuous social flow (Crevani et al., 2010). It recognizes and draws attention to the social structuring of leadership, seeing pre-existing technical expertise and role definition as both vitally important but also insufficient for project leadership in the dynamically changing contexts in which contemporary projects intervene. There is a need for more attention to three inter-related areas of transformation: changing technologies, where the related choices have an ethical dimension, engaging with a multiplicity of values; growing organizational complexity with multiple actors and emerging complexity and uncertainty, together with the demands for projects to intervene positively to create sustainable, resilient and just futures. It is transitions in these three areas that are disrupting and reforming the boundaries around projects, posing questions concerning their value regimes and leadership, posing new opportunities for leadership that orchestrates and values a diversity of knowledge.

In the next section, we begin by outlining what we take to be the essentials of project leadership in the contemporary context. In the following section we then draw out the research insights and directions for further research related to these three transitions, articulating how projects as interventions, shaped by and shaping wider technological, social and ecological contexts, require leadership through new forms of engagement and collaboration with a range of actors. We discuss possible future research questions that can lead to further insight, concluding by summarizing the contribution and proposing next steps for future research.

2. Project leadership in the context of contemporary leadership approaches

Within the literature on project leadership there is a substantial trajectory of research that is focused on the leader as an individual with specific characteristics (e.g. Zaccaro and Day, 2014; Merrow and Nandurdikar, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Yet, we argue that the study of project leadership cannot be limited to studying ‘the leader’, as an individual, with a personality type, leadership style or personal career trajectory. Leadership becomes enacted in practices and interactions (Crevani et al., 2010) that are distributed across interorganizational projects and the contexts in which they deliver. In our changing world, where project contexts are in flux, they are delivered in the context of changing technologies, with the digitalization of delivery and deliverables presenting new challenges; of organizational dynamics, with increasing stakeholder complexity associated with greater inclusivity of interests; and of ecological concerns, with the salience of questions of sustainablity and resilience..

چکیده

1. مقدمه

2. رهبری پروژه در چارچوب رهبری معاصر نزدیک می شود

3. بینش ها و جهت گیری ها را تحقیق کنید

3.1. در حال تغییر تکنولوژی ها

3.2. پیچیدگی سازمانی: پویایی پروژه ها

3.3. پروژه هایی برای آینده پایدار و تاب آور

4. بحث

5. نتیجه گیری ها

منابع

ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

2. Project leadership in the context of contemporary leadership approaches

3. Research insights and directions

3.1. Changing technologies

3.2. Organizational complexity: dynamics of projects

3.3. Projects for sustainable and resilient futures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References