دانلود رایگان مقاله مدل های نظری و عملیاتی در تحقیقات مکان یابی هتل

2. مدل نظری

مدل های نظری, فنداسیون نظری برای انتخاب موقعیت فضایی هتل ها را ایجاد نموده اند. تئوری ها از نظام های مختلف برای توضیح دیدگاه های مختلف در مورد موقعیت هتل استفاده شده اند. این تئوری ها شامل تئوری های جغرافیایی (Egan and Nield, 2000; Shoval, 2006), اقتصادی, (Kalnins and Chung, 2004) و تئوری های بازاریابی (Baum and Haveman, 1997; Urtasun and Gutiérrez, 2006) می شوند. ما مدل های نظری قبلاً مستندسازی را به چهار نوع بر اساس پیش زمینه های سیستم آنها رده بندی نموده ایم و آنها مدل شهر تاریخی-توریستی, مدل تک-محور, مدل تراکم و مدل چندبعدی می شوند.

2.1 مدل شهر تاریخی-توریستی (مدل THC)

قدمت مدل های THC به نوع شناسی جامع Ashworth and Tunbridge’s (1990) موقعیت های هتل درون شهرهای استانی اروپای غربی باز می گردد. در کار خود، شش نوع از مناطق محل، مشخص شندد، از جمله دروازه شهر سنتی (A)، جاده های راه آهن / نزدیک شدن به ایستگاه (B)، جاده های دسترسی اصلی (C)، مکان "خوب" (D)، مناطق گذار و حاشیه شهری در شاهراه (E) و تبادلات فرودگاه حمل و نقل (F). این مناطق مختلف با انواع مختلف از هتل ها در ارتباط هستند. به عنوان مثال، هتل های بزرگ و مدرن را می توان در موقعیت های نوع E و نوع F یافت, در حالیکه هتل های کوچک و متوسط در موقعیت های نوع D قالب هستند. آنها این خوشه ها را به تاثیر دسترسی, ارزش های زمین, راحتی محیطی, تداوم تاریخی و سیاست استفاده از زمین منسوب نمودند.

در مطالعات گردشگری و مهمان نوازی، یک سنت طولانی از استفاده از مدل THC برای بررسی محل هتل و توزیع فضایی در شهرهای توریستی-تاریخی وجود دارد. مشخص شده است که بسیاری از شهرهای گردشگری, الگوی توزیع هتل فرض شده توسط مدل THC را نشان می دهند. Burtenshaw و همکاران (1991), مدل THC را برای توضیح نوع شناسی توزیع هتل در چند شهرهای اروپا اعمال نمودند. برای تفسیر تکامل هتل از دیدگاه فضایی، Timothy و Wall (1995) محل اقامت در یوگیاکارتا، اندونزی را مورد مطالعه قرار دادند و کشف کردند که مدل THC به طور منطقی می تواند محل هتل ها را توضیح دهد و طبقه بندی مکانی تسهیلات را پیش بینی نماید. علاوه بر این، Oppermann و همکاران (1996) از این مدل برای بحث در مورد توزیع هتل در کوالالامپور، مالزی استفاده نمودند. در مطالعه خود، هفت نوع از مناطق محل، مشخص شدند و برجسته ترین آنها, "محل جدید مرکز کسب و کار منطقه ای بود". این شامل هتل های مدرن بزرگ و مراکز خرید لوکس بود که در کشورهای جنوب شرقی آسیا رایج هستند. Rogerson (2012a) نیز, اهمیت CBD در جذب هتل ها در سه شهرهای آفریقای جنوبی و برخی از مکان های "خوب" برای هتل های توصیف شده در مدل THC را مشخص نمود.

در مطالعه دیگری توسط Begin (2000)، مشخص شد که محل هتل در Xiamen، چین، به طور کلی با محل های شرح داده شده در مدل THC همزمان است. تعداد زیادی از هتل های ارزان در مرکز تاریخی خوشه بندی شدند، و هتل های جدید در منطقه انتقال بین مرکز شهر قدیمی و CBD در حال ظهور ساخته شده بدند. Shoval و Cohen-Hattab (2001) محل اقامت گردشگری در اورشلیم، اسرائیل در بیش از 150 سال گذشته را بررسی کردند. با تمرکز بر روی چهار دوره از توسعه، این مطالعه, پیش بینی های مدل THC را تایید کرد. همچنین عوامل مهم دیگر شکل دادن به توزیع هتل، مانند تحولات سیاسی و تفاوت های اجتماعی و فرهنگی بین گروه های جمعیتی برجسته شد. Aliagaoglu و Ugur (2008) دریافتند که نتایج حاصل از Dökmeci و Balta (1999) در الگوی محل هتل در استانبول، ترکیه, پیش بینی مدل THC را تایید می کند و هر دو مکان های نوع A و نوع E در شهر شناسایی شدند.

ارزش مدل THC در سادگی و ایجاز آن برای در نظر گرفتن نقاط محل اصلی برای هتل ها و آرایش فضایی عمومی در شهر توریستی نهفته است. اگر چه مدل THC در نوشته های گردشگری بسیار محبوب است، دارای محدودیت های بسیاری است. اول، همانطور که توسط Ashworth and Tunbridge (2000), نشان داده شده است، این مدل, به جای توضیحی بودن, طبقه بندی است. به این ترتیب، حتی اگر محل بالقوه برای هتل ها در داخل شهر را بتوان شناسایی کرد، ما دلیل دقیق این مورد را درک نمی کنیم چرا این محل انتخاب می شود. جدای از آن، در حالی که مشخص شده است این مدل برای شهرهای توریستی-تاریخی قابل کاربرد است، ممکن است برای شهرهای غیر توریستی تاریخی مناسب نباشد (Aliagaoglu و Ugur، 2008؛ د Brès را، 1994). با این حال، اگر قابل اجرا باشد، پس، چه بهبود و یا تغییراتی باید برای تهیه کردن به این وضعیت جدید صورت گیرد؟

2.2 مدل تک-محور

مدل تک-محور, توزیع الگوهای استفاده از زمین را به صورت حلقه های تک-محور به فاصله از مرکز شهر توصیف می کند و بر اهمیت عالی قابلیت دسترسی در شکل دهی به این الگو (Alonso, 1964; Von Thünen,, 1826) تاکید می کند. در این مدل، فرض بر این است که یک منطقه شهری تک-محور با یک نقطه مرکزی واحد برای پراکندگی است، و منحنی پیشنهاد اجاره برای به تصویر کشیدن میزان تمایل کاربران زمین به پرداخت برای مکان ها با نزدیکی های مختلف به مرکز معرفی شده است. بر اساس اصل منحنی های پیشنهاد-اجاره، و برگرفته از مدل استفاده از زمین Von Thünen’s ، Yokeno (1968) یک مدل تک محور برای برجسته نمودن مکان احتمالی هتل های شهری را پیشنهاد کرد. با این فرضیه که گردشگران حاضر به پرداخت بیشتر در ازای دسترسی آسان به مرکز شهر می باشند، مدل جدید نشان می دهد که منطقه هتل در مرکز شهر، واقع بین CBD درونی در شهر و مناطق تجاری (شکل 2a) است.

Egan و Nield (2000) مدل تک محور دیگری از رویکرد جزئی تعادل پیشنهاد-اجاره استنتاج نمود و سلسله مراتب فضایی هتل ها را از نظر فاصله تا مرکز شهر توضیح داد. منحنی های زمین پیشنهاد اجاره, درآمد مرتبط با مکان را برجسته نمودند و فرض بر این است که درآمد هتل ها, زمانی افت می کند که آنها در مکان هایی دور از مرکز قرار می گیرند. در این مدل، اولویت محل هتل ها از سطوح مختلف را می توان با شکل منحنی پیشنهاد اجاره در ارتباط با آنها پیش بینی کرد. انتظار می رود هتل های لوکس (چهار / پنج ستاره) دارای یک منحنی پیشنهاد اجاره بسیار تند و بالا باشند و یک محل مرکزی را ترجیح می دهند (شکل 2B). دلیلش این است که نرخ های اتاق بالاتر با هدف قرار دادن مهمانان مرفه به احتمال زیاد ارزش های زمین بالاتر در ارتباط با یک محل مرکزی را پوشش می دهد. در مقابل، با توجه به درآمد کافی برای پرداخت به یک محل مرکزی، هتلها, مکانی در لبه شهر ها را انتخاب می کنند و یا ساختمان های تبدیل شده در لبه مرکز شهر را انتخاب می کنند. برای اعتبارسنجی بیشتر عمومیت مدل Egan و Nield (2000)، Egan et al. (2006) ، هتل ها در سه شهرهای کلان چینی را تست نمودند. نتایج آنها نشان داد که محل هتل در این شهرهای به طور کلی با وجود برخی معایب جزئی, برازش خوبی با مدل دارند. مشخص شده است که بسیاری دیگر از شهرهای شامل یک سلسله مراتب فضایی و آرایش متحد المرکز از توزیع هتل می شوند که شبیه به مدل Egan و Nield (2000) است, مانند کیپ تاون، دوربان، و Port Elizabeth در آفریقای جنوبی (Rogerson، 2012a) و کلانشهر کوماسی در غنا (Adam، 2013).

علاوه بر این، Shoval (2006) نشان داد که مدل (1968) Yokeno قادر به پیش بینی محل هتل در اورشلیم، اسرائیل بود. او یک مدل توسعه یافته با شناخت دو جغرافیای مورد تقاضا برای هتل ها را ارائه نمود: منطقه هتل برای گردشگری انفرادی و برای گردشگری سازمان (شکل2c).. بازارهای مختلف با منحنی های مختلف پیشنهاد اجاره مطابقت دارند. در یک مطالعه تجربی جامع تر انجام شده توسط Yang و همکاران (2012)، مدل تک محور برای توضیح این سلسله مراتب فضایی توزیع هتل در پکن، چین مورد استفاده قرار گرفت. بر اساس تجزیه و تحلیل پیشنهاد اجاره، مدل تک محور همچنین می تواند برای مطالعه شهر با مراکز دوگانه تعمیم داده شود و یک سلسله مراتب فضایی همپوشانی از مکان های هتل در هر مرکز شناسایی شده است (Egan et al., 2006; Lee and Jang, 2011).

در مجموع، مدل های تک محور , یک ابزار قدرتمند تحلیلی، تجزیه و تحلیل پیشنهاد-اجاره، را برای نگاه به محل هتل و فعالیت های دیگر در محدوده کل شهر فراهم می کنند. به طور کلی، این مدل ها, نیروی مرکز در محل هتل مجلل را برجسته می نمایند. چند مطالعات تجربی, سودمندی این مدل را در پیش بینی آرایش فضایی هتل در شهر حمایت کرده اند. با این حال، به دلیل پیچیدگی مسئله محل هتل، مدل تک محور به بررسی تحت شرایط مختلف ساده (Shoval، 2006، ص 63) می پردازد و برخی از آنها برای موارد محل هتل عمومی بیش از حد غیر واقعی تلقی می شوند. به عنوان مثال، این فرض درست نیست که این شهر به صورت یک تک محور در بیشتر مواضع (Lee and Jang، 2011) و محل مرکزی به عنوان بزرگ و یا حتی تنها ترجیح مهمانان هتل فرض شود. علاوه بر این, مدل تک-محور به طور مناسب تمام جنبه های الگوهای موقعیت هتل را در بر نمی گیرد و از آن مهم تر, موفق به توضیح تراکم هتل خرد-مقیاس (Egan et al., 2006) نمی شود که به عنوان دلیل رایج پذیرفته شده است.

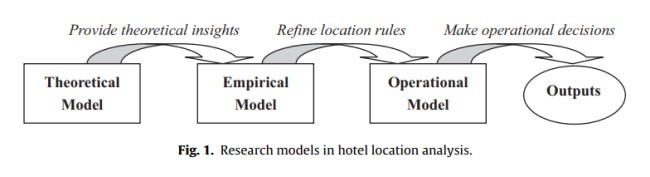

2. Theoretical model

Theoretical models establish the theoretical foundation for the spatial location choice of hotels. Theories from different disciplines have been used to explain different perspectives on hotel location. These theories include geographical (Egan and Nield, 2000; Shoval, 2006), economic (Kalnins and Chung, 2004) and marketing theories (Baum and Haveman, 1997; Urtasun and Gutiérrez, 2006). We categorize previously documented theoretical models into four types based on their disciplinary backgrounds, and they are the touristhistoric city model, the mono-centric model, the agglomeration model, and the multi-dimensional model.

2.1. Tourist-historic city model (THC model)

THC models date back to Ashworth and Tunbridge’s (1990) comprehensive typology of hotel locations within medium-sized Western European provincial towns. In their work, six types of location zones were identified, including traditional city gates (A), railway station/approach roads (B), main access roads (C), “nice” locations (D), transition zones and urban periphery on motorway (E), and airport transport interchanges (F). These different zones are associated with different types of hotels. For example, large modern hotels can be found in type E and type F locations, whereas small and medium hotels dominate type D locations. They attributed these clusters to the influence of access, land values, environmental convenience, historical continuity, and land-use policy.

In tourism and hospitality studies, there is a long tradition of applying the THC model to investigate hotel location and spatial distribution in tourist-historic cities. Most tourist cities have been found to exhibit a hotel distribution pattern postulated by the THC model. Burtenshaw et al. (1991) applied the THC model to explain the typology of hotel distribution in several European cities. To interpret hotel evolution from a spatial perspective, Timothy and Wall (1995) studied the accommodation in Yogyakarta, Indonesia and discovered that the THC model can reasonably explain the location of hotels and predict the locational classification of accommodations. Furthermore, Oppermann et al. (1996) used this model to discuss the hotel distribution in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. In their study, seven types of location zones were recognized, and the most distinguished was the “new Central Business District location.” This included large modern hotels and deluxe shopping centers, which are common in Southeast Asian countries. Rogerson (2012a) also highlighted the importance of CBD in attracting hotels in three cities of South Africa, and identified some “nice” locations for hotels as described in the THC model.

In another study by Bégin (2000), it was found that hotel locations in Xiamen, China, in general, coincided with those described in the THCmodel. A large number of cheap hotels were clustered in the historical center, and new hotels were constructed in the transition zone between the old downtown and the emerging CBD. Shoval and Cohen-Hattab (2001) investigated the location of tourism accommodations in Jerusalem, Israel over the past 150 years. Focusing on four periods of development, the study confirmed the predictions of the THC model. It also highlighted other important factors shaping hotel distribution, such as political upheavals and social and cultural differences between the population groups. Aliagaoglu and Ugur (2008) found that the results from Dökmeci and Balta (1999) on hotel location pattern in Istanbul, Turkey confirmed the THC model’s prediction, and both type A and type E locations in the city were identified.

The value of the THC model lies in its simplicity and briefness to consider major location hotspots for hotels and the general spatial arrangement within a tourist city. Although it is very popular in the tourism literature, the THC model is subject to many limitations. First, as indicated by Ashworth and Tunbridge (2000), the model is taxonomic rather than explanatory. As such, even though the potential location for hotels within the city can be identified, we do not understand the exact reason why it is selected. Apart from that, while this model has been found to be applicable to touristhistoric cities, it may not be appropriate for non-tourist-historic cities (Aliagaoglu and Ugur, 2008; De Bres, 1994). If it is applicable, however, then, what improvements or modifications should be made to cater to this new situation?

2.2. Mono-centric model

The mono-centric model describes the distribution of land use patterns as several mono-centric rings according to the distance from the city center and emphasizes the paramount importance of accessibility in shaping this pattern (Alonso, 1964; Von Thünen, 1826). In the model, it is assumed that an urban area is monocentric with a single central point for sprawl, and the bid-rent curve is introduced to depict how much land users are willing to pay for locations with different proximities to the center. Based on the principle of bid-rent curves, and drawn from Von Thünen’s (1826) land-use model, Yokeno (1968) proposed a mono-centric model to highlight the possible location of urban hotels. With an assumption that tourists are willing to pay more in return for easy access to the city center, the new model suggested that the hotel district is in the center of the city, located between the city’s innermost CBD and commercial zones (Fig. 2a).

Egan and Nield (2000) derived another mono-centric model from the partial-equilibrium bid-rent approach, and explained the spatial hierarchy of hotels in terms of the distance to the city center. Land bid-rent curves highlight the revenue associated with locations, and it is assumed that hotels’ revenue falls when they move to locations away from the center. In the model, the location preference of hotels of different levels could be predicted by the shape of the bid-rent curve associated with them. Luxury hotels (four-/fivestar) are expected to have a very steep and high bid-rent curve and prefer a central location (Fig. 2b). This is because their higher room rates targeting affluent guests are likely to cover the higher land values associated with a central location. Conversely, due to insufficient revenue to pay for a central location, budget hotels choose to either locate at the edge of the city, or select converted buildings at the edge of the city center. To further validate the generality of Egan and Nield’s (2000) model, Egan et al. (2006) tested hotels in three Chinese metropolises: Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. Their results suggested that the hotel location in these cities generally fit the model well, despite some minor flaws. Many other cities have been found to contain a spatial hierarchy and concentric arrangement of hotel distribution that is analogous to Egan and Nield’s (2000) model, such as Cape Town, Durban, and Port Elizabeth in South Africa (Rogerson, 2012a) and the Kumasi Metropolis in Ghana (Adam, 2013).

In addition, Shoval (2006) demonstrated that Yokeno’s (1968) model was capable of predicting hotel location in Jerusalem, Israel. He proposed an extended model by recognizing two geographies of demand for hotels: the hotel area for individual tourism and for organized tourism (Fig. 2c). Different markets corresponded to different bid-rent curves. In a more comprehensive empirical study conducted by Yang et al. (2012), the mono-centric model was used to explain this spatial hierarchy of hotel distribution in Beijing, China. Based on the bid-rent analysis, the mono-centric model can also be generalized to study the city with dual centers, and an overlapped spatial hierarchy of hotel locations to each center has been identified (Egan et al., 2006; Lee and Jang, 2011).

In sum, mono-centric models provide a powerful analytical tool, bid-rent analysis, to look into hotel location and other activities within the scope of the whole city. In general, these models highlight a centripetal force on upscale hotel locations while a centrifugal force on downscale ones. Several empirical studies have supported the usefulness of this model in predicting the spatial arrangement of hotels within a city. However, because of the complexity of the hotel location problem, the mono-centric model investigates it under several oversimplified conditions (Shoval, 2006, p. 63), and some of them have been deemed too unrealistic for general hotel location cases. For example, it is inappropriate to assume that the city as a mono-centric one in most situations (Lee and Jang, 2011) and posit the central location as the major or even the sole preference of hotel guests. Moreover, the mono-centric model does not adequately capture all aspects of hotel location patterns, and most importantly, it fails to explain micro-scale hotel agglomeration (Egan et al., 2006), which has been accepted as conventional wisdom.

2. مدل نظری

2.1 مدل شهر تاریخی-توریستی (مدل THC)

2.2 مدل تک-محور

2.3 مدل تراکم

2.4. مدل چند بعدی

3. مدل تجربی

3.1. مدل آماری فضایی

3.2. مدل رگرسیون منطقه بندی

3.3. مدل انتخاب گسسته

3.4. مدل معادلات همزمان

3.5. مدل ارزیابی فردی

3.6. مدل موفقیت هتل

4. مدل عملیاتی

4.1. روش چک لیست

4.2. پیش بینی آماری

4.3. سیستم اطلاعات جغرافیایی (GIS)

5. بحث و بررسی

5.1. یافته های پژوهش های قبلی

5.2. جهات تحقیقاتی آینده

6. نتیجه گیری

2. Theoretical model

2.1. Tourist-historic city model (THC model)

2.2. Mono-centric model

2.3. Agglomeration model

2.4. Multi-dimensional model

3. Empirical model

3.1. Spatial statistical model

3.2. Zoning regression model

3.3. Discrete choice model

3.4. Simultaneous equation model

3.5. Individual evaluation model

3.6. Hotel success model

4. Operational model

4.1. Checklist method

4.2. Statistical prediction

4.3. Geographic Information System (GIS)

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings of previous research

5.2. Future research directions

6. Conclusion

References