دانلود رایگان مقاله ضدیت با مصرف به مثابه ابزاری جهت حفظ مشاغل

چکیده

هدف: هدف از این مقاله، بررسی این موضوع است که انگیزه های مختصِ فرد، تا چه اندازه باعث مشارکت مصرف کننده در طرح بایکوت میشود و انگیزه های مختلفِ پذیرندگان (نوآوران، کُندکاران) تا چه اندازه با هم فرق دارند. این پژوهش به دنبال شرحِ این موضوع است که انگیزه های بایکوت تا چه اندازه در مقاومت مشتری و ضدیت با مصرف جای دارند.

طراحی/متدولوژی/رویکرد- رویکرد این مقاله، آمیزه ای از روشهای کمّی و کیفی است. مطالب یا پُست های اینترنتیِ 790 حامیِ بایکوت را با استفاده از یک تحلیل محتوا، آنالیز کردیم. ربط مندیِ انگیزه های مختلف را از طریق تحلیل فراوانی مورد بررسی قرار دادیم. تحلیل احتمالِ وقوع را نیز جهت واکاویِ انگیزه های خاصِ هر بخش بکار گرفته ایم.

یافتهها – این پژوهش با استفاده از مثالی از نقل مکانِ کارخانه، چندین انگیزه ی خاصِ فردی را که وابسته به علتِ بایکوت هستند، شناسایی میکند و تایید میکند که انگیزه های پذیرندگان مختلف، با هم فرق دارد. افرادی که شخصاً تحت تاثیر قرار گرفتهاند یا احساس همبستگی با کسانی دارند که تحت تاثیر قرار گرفتهاند، زودهنگامتر از سایرین به طرح بایکوت میپیوندند، اما کسانی که دیرتر به بایکوت ملحق میشوند، نقاط قوت و ضعف بایکوت را منطقیتر میسنجند.

محدودیتهای پژوهشی/رهآوردها- پژوهشهای بیشتری باید روش های پژوهشیِ کیفی را بکار گیرند تا از ثبات یافتهها اطمینان یابند. رواییِ خارجی نیز باید برای انواع بایکوت های مختلف آزموده شود.

رهآوردهای عملی- برخی مشتریان به این دلیل به بایکوتها ملحق میشوند که با کسانی که تحت تاثیر اقدامات یک شرکت قرار گرفته اند، احساس همبستگی میکنند (بایکوتکنندگانِ مقاومتی)؛ اما سایر افراد کلاً اقتصاد بازارِ آزاد را مورد انتقاد قرار میدهند و عموماً مستعدِ بایکوت کردنِ هر شرکتی میباشند (بایکوتکنندگانِ ضدیت با مصرف). شرکتها باید مطمئن شوند که هر دو نوع بایکوت کنندهها، خود را در قبال جامعه مسئول میدانند.

اصالت/ ارزش- پژوهشِ حاضر شواهدی ارائه میدهد مبنی بر اینکه انگیزههای بایکوت، وابسته به مورد هستند. بعلاوه، این نخستین پژوهشی است که نشان میدهد انگیزههای پیوستن به یک بایکوت، تا چه اندازه در طول زمان تغییر میکنند.

1. مقدمه و پیشینه

با توجه به رشد وابستگیِ متقابل اقتصادهای جهانی، روز به روز بر تعداد کارکنانی افزوده میشود که در کشورهای صنعتیِ مُزد-بالا مشغول بکارند و نگران از دست دادن شغل خود هستند، به این خاطر که شرکتهای چندملیتی که این افراد در آنها مشغول بهکار هستند، ممکن است شعب فرعی خود را از این کشورها به کشورهای مُزد-پایین منتقل نمایند. از آنجاکه دولتها اغلب کنترلی بر تصمیمات مرتبط با جابجاییِ شرکتها ندارند، سازمانهای غیردولتی در تلاش هستند تا با فراخواندن مردم به عدم خرید کالا از این شرکتها، این خلاء را پر کنند. این نوع کنشِ سیاسی اینگونه تعریف میشود: «تلاشی که توسط یک گروه یا گروه هایی انجام میگیرد تا با تشویق مصرفکننده ها به خودداری از خرید کالاهایی خاص، به اهداف مشخصی دست یابند». تعداد زیادی از مصرفکننده ها از این بایکوتها (تحریمها) حمایت میکنند تا به کنترل شرکتهای چندملیتی کمک کرده و دست به اقدام متقابل زده باشند و ناخرسندی خود را ابراز کرده باشند. مثلاً 39 درصد از مصرف کننده های آلمانی توافق دارند که شرکتهایی که تعداد کارکنان خود را کاهش میدهند، علیرغم اینکه سود خوبی عایدشان میشود، باید بایکوت شوند. موج پنجمِ بررسی جهانیِ ارزشها (انجمن بررسی جهانیِ ارزشها، 2009) نشان میدهد که درصد قابل توجهی از جمعیت در کشورهای صنعتی، قبلاً به دلیل فوق یا به دلایل دیگر، در بایکوت شرکتها مشارکت کرده اند؛ مثلاً:

* سوئد: 27.9 درصد؛

* کانادا: 21.6%

* ایالات متحده آمریکا: 21.2%

*ایتالیا: 19.7%

*بریتانیا: 17.2%

*استرالیا: 16.7%

*فرانسه: 13.7%

آلمان: 8.8%

از آنجا که بایکوت تاثیری منفی بر شهرت و وجهه و فروش و قیمت سهام شرکتِ مورد نظر میگذارد و چون بایکوت تاثیر بالقوه ای بر تغییر اجباریِ خط مشیِ شرکت دارد، این پرسش که چه انگیزه هایی میتواند مشتریان را به پیوستن به بایکوت ترغیب کند، هم از منظر اجتماعی و از منظر مدیریتی، پرسشی در خورِ توجه است.

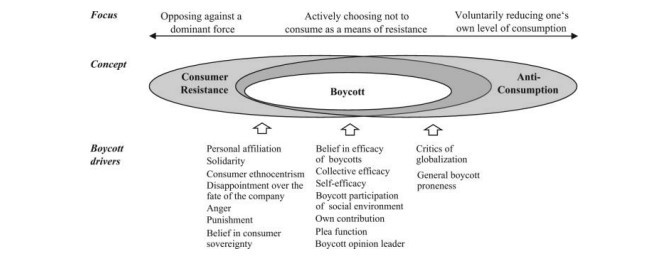

بایکوت شرکتها را میتوان نوعی ضدیت با مصرف تلقی کرد، که راهکاری جهت مقاومتِ مصرف کننده بشمار میرود. مفاهیم ضدیت با مصرف و مقاومتِ مصرف کننده، در جنبه های متعددی با هم اشتراک دارند. با اینحال در حالی که ضدیت با مصرف همیشه بصورت خودداری از مصرف تعبیر میشود، مقاومتِ مصرف کننده از مصرف فعالِ کالاهای خاص تشکیل میشود (یعنی مصرف کالاهای مشابه از سایر تولیدکننده ها). پدیده ی بایکوت از جانب مشتری، مثالی روشن از همپوشانی این دو مفهوم است. این پدیده، کاهش داوطلبانه ی سطح مصرفِ برخی کالاها یا یک برند (که مشخصه ی بارز ضدیت با مصرف است) را با تمایل به مخالفت با نیروی غالب و حاکم (که بُعد اصلی مقاومت مصرف ک ننده هست)، ادغام میکند. در سنخ شناسیِ (توپولوژی) آیِر و مونسی از ضدیت با مصرف، بایکوت کنندگان را میتوان فعالانی از بازار تلقی کرد که نه به دلایل شخصی و فردی بلکه به دلایل اجتماعی، برنده ای خاصی را بهجای عدمِ مصرف، بطور کلی رد میکنند.

در بازه ی زمانی 1976 تا 2009، سیزده مقاله به تحلیل تجربیِ روایت هایی پرداختهاند که افراد از مشارکتشان در بایکوتها بازگو کردهاند. جهت تلخیص این روایت ها و واگویه ها، به رده بندی این سه مقوله ی متمایز اقدام کردیم:

1) محرک ها

2) تشویقگران

3) بازدارنده ها

محرکها متغیرهایی هستند که فرد را به فکر مشارکت در یک بایکوت می اندازند. تشویقگران مصرفکننده ها را به پیوستن به این حرکت ترغیب میکنند، اما بازدارنده ها دلایلی برای لزوم عدم شرکت در بایکوت ارائه میدهند (تصویر 1). تنها تعداد معدودی از پژوهش ها به بررسی روایتهایی پرداخته اند که میتوان آنها را در زمره ی مقوله ی «محرک»ها قرار داد. این پژوهش ها بر احساسات منفی نظیر خشم و ناراحتی تمرکز دارند. دو نوع تشویقگر را میتوان معرفی نمود. یک نوع، بر ره آوردها و تبعات مشارکت در بایکوت تاکید میکند، از جمله میل به کنشِ اخلاقی و تلاش برای خودافزایی. نوع دوم، بر اثربخشیِ بایکوت تاکید دارد که هم در سطح فردی و هم در سطح عمومی، تجزیه و تحلیل شده است. چند نمونه بازدارنده نیز در نشریات پژوهشی مورد بحث و بررسی قرار گرفته اند. از آنجاکه بایکوت دلالت بر این دارد که فردی الگوی پیشینِ مصرف خود را محدود کند، اما اگر وی به آن کالا علاقه داشته باشد یا جایگزین مشابهی برایش نیابد، احتمال مشارکتش در بایکوت ضعیف میشود. بعلاوه، استدلالهای متقابل نظیر احساس بیقدرتی کردن، فرد را از مشارکت در بایکوت باز میدارد. هرچه مصرفکنندگان اعتماد بیشتری به مدیریت شرکت داشته باشند، احتمال بایکوت کردن آن شرکت کمتر است.

با توجه به اینکه بایکوتها علل و اهداف مختلفی دارند، لازم است دانشمندان مکانیزم های ویژگینگرِ مشارکت را برای هر نوع بایکوت بکار گیرند (مثلاً، بایکوتهای کاری، مذهبی و زیستبومی). پژوهش های اولیه حاکی از این هستند که برخی از این انگیزهها فراگیر هستند و برخی به نوع خاصی از بایکوت منحصر میباشند. مثلاً مصرفک نندهها کاراییِ ادراکشده و احتمال بهره وریِ بیهزینه را در خصوص انواع مختلف بایکوتها مدنظر قرار میدهند (مثلاً بایکوت ناشی از آزمایش هایی که روی حیوانات انجام میگیرند، به دلیل افزایش قیمت یا بستن کارخانه ها). بنظر میرسد که این روایتها فراگیر باشند، در حالیکه سایر محرک ها مختص به مورد (موردی) میباشند. مثلاً برای بایکوتهایی که به دلیل بستن کارخانه ها انجام میگیرند، دانشمندان قبلاً محرک هایی خصیص های را شناسایی کرده اند؛ مثلاً خطرِ اثر بازگشتی (بومرنگی) یا شهرتِ شعب های که قرار است بسته شود، که قابل انتقال به سایر انواع بایکوتها نیستند. احتمالاً شرکت در این نوع بایکوت نیز ناشی از فاکتورهای متعددی است که تا کنون نادیده گرفته شده اند، نظیر همبستگی با کارگرانِ بیکارشده و نگرش منفی نسبت به جهانی سازی. در مقابل، مشارکت در سایر بایکوتها ناشی از سایر محرکهای خصیص های میباشد. جهت درک و شناخت جامعتر از شرکت در بایکوت، اهمیت تحقیقات موردی را هایلایت میکنیم. اثبات میکنیم که اتکا به محرکهای بایکوت، ناشی از نظریهه ای عمومیِ بایکوت میباشد که از تصویر ناکاملِ مشارکت استفاده میکنند. ما به بررسی این موضوع میپردازیم که آیا به این دلیل که دانشمندان تحقیقاتشان را عمدتاً بر مبنای نظریه های کلیِ تحریم گذاشتهاند، محرک های ویژهی فردیِ مشارکت، مورد غفلت و بی توجهی واقع شده اند یا خیر. ما مثال خود را از بایکوتهای مرتبط با نقل مکانِ کارخانه برگزیده ایم، چراکه نقل مکانِ کارخانه ها از نقطه نظرِ عملی بسیار مرتبط میباشند. در کشورهای صنعتی، بیم از بیکاریِ ناشی از نقل مکان کارخانه ها به کشوری دیگر، افراد بسیاری را به بایکوت کالاهای آن کارخانه تحریک میکند تا از خروج کارخانه جلوگیری نمایند یا دستکم علیه برون سپاریِ تولید محصولات اعتراض کرده باشند. پس از اینکه نوکیا خواست شعبه ی خود در آلمان را به رومانی منتقل کند، 56 درصد از مصرف کننده های آلمانی قصد داشتند از خرید گوشی های نوکیا اجتناب نمایند.

Abstract

Purpose – The paper aims to explore how idiosyncratic motives drive participation in consumer boycotts and how the motives of different adopters (e.g. innovators, laggards) differ. The study seeks to describe how boycott motives are embedded in the fields of consumer resistance and anti-consumption.

Design/methodology/approach – The paper applies a mixed-method approach of qualitative and quantitative methods. Internet postings of 790 boycott supporters are analyzed by means of a content analysis. The relevance of different motives is examined via frequency analysis. Contingency analysis is applied to explore segment-specific motives.

Findings – Using the example of factory relocation, the study identifies several idiosyncratic motives that are contingent to the boycott cause. Additionally, it confirms that the motives of different adopters differ. Individuals who are personally affected or feel solidarity with those affected join the boycott relatively early whereas those who join later consider the pros and cons of the boycott more rationally.

Research limitations/implications – Further research should apply quantitative research methods to ensure the stability of the findings. The external validity needs to be tested for different boycott types.

Practical implications – Some consumers join boycotts because they feel solidarity with those affected by the actions of a company (resistance-boycotter), whereas others generally criticize the free-market economy and are generally prone to boycott any company (anti-consumption-boycotters). Companies need to ensure that both types of boycotters consider them socially responsible.

Originality/value – This study provides evidence that boycott motives are case-contingent. Additionally, this is the first study to demonstrate how motives for joining a boycott vary in the course of time.

1. Introduction and background

Given the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, more and more employees in high-waged industrialized countries are afraid of losing their jobs because multinational enterprises shift subsidiaries to low-wage countries. As national governments often have no control over these relocation decisions, non-governmental organizations try to fill the vacuum of control by calling out consumer boycotts. This type of political action is defined as “an attempt by one or more parties to achieve certain objectives by urging individual consumers to refrain from making selected purchases in the market place” (Friedman, 1985, p. 97). A large number of consumers follow boycott calls to help control multinational enterprises, to retaliate or to vent their frustration (Hoffmann and Mu¨ller, 2009; Klein et al., 2004, Shaw et al., 2006). For example, 39 percent of German consumers agree that companies that reduce jobs, despite making good profits, should be boycotted (Infratest-Dimap, 2006). The fifth wave of the World Values Survey (World Values Survey Association, 2009) shows that a substantial percentage of the population in industrialized countries have already taken part in boycotts for this or other reasons, for example:

. Sweden: 27.9 percent;

. Canada: 21.6 percent;

. US: 21.2 percent;

. Italy: 19.7 percent;

. UK: 17.2 percent;

. Australia: 16.7 percent;

. France: 13.7 percent; and

. Germany: 8.8 percent.

Since boycotts negatively affect the target company’s reputation, sales, and stock price and since they are potentially effective to force change in corporate policy (Davidson et al., 1995) the question of what motivates consumers to join boycotts is relevant from both a managerial and a societal perspective.

Boycotts can be considered a type of anti-consumption, which is a means of consumer resistance. The concepts of anti-consumption (Zavestoski, 2002; Lee et al., 2009) and consumer resistance (Cherrier, 2009; Penaloza and Price, 1993; Roux, 2007) have several aspects in common. However, while anti-consumption is always expressed as the abstention from consumption in a certain domain, consumer resistance also comprises active consumption of specific goods (e.g. consumption of the goods of alternative producers or participation in co-ops). The phenomenon of consumer boycotts is a demonstrative example of the overlap of both concepts. It combines the voluntary reduction of one’s own level of consumption regarding at least one domain or brand, which is a striking characteristic of anti-consumption, with the wish to oppose a dominant force, which is a central aspect of consumer resistance. Within Iyer and Muncy’s (2009) typology of anti-consumers, boycotters can be ascribed to the market activists who reject specific brands rather than refraining from consumption in general for societal rather than personal reasons.

In the period from 1976 to 2009, thirteen articles have empirically analyzed the individual antecedents of boycott participation. To systematize these antecedents, we introduce a taxonomy of three distinct categories:

(1) triggers;

(2) promoters; and

(3) inhibitors.

Triggers are variables that prompt the individual to consider participating in a boycott. Promoters encourage consumers to join, while inhibitors provide reasons not to take part (Figure 1). Only few studies investigate antecedents that can be assigned to the category triggers. These studies focus on negative emotions, such as anger or perceived egregiousness (Klein et al., 2004; Nerb and Spada, 2001). Two types of promoters can be identified. One emphasizes the moral implications of boycott participation including the desire to act morally and the striving for self-enhancement (Klein et al., 2004; Kozinets and Handelman, 1998). The second type concerns boycott effectiveness, which has been analyzed on the individual level (self-efficacy) as well as on a general level (perceived likelihood of success; Sen et al., 2001). Several inhibitors have been discussed in literature. Since boycotting implies constraining one’s previous patterns of consumption, the consumer is less likely to participate if he likes the product and if there are no adequate substitutes (Sen et al., 2001). Furthermore, counter-arguments such as the perceptions of powerlessness impede participation (Klein et al., 2004). The more consumers trust in the management, the less likely they are to boycott (Hoffmann and Mu¨ller, 2009).

Given that boycotts have different causes and different objectives (Friedman, 1999), scholars need to examine the idiosyncratic mechanisms of participation for each particular type of boycott (e.g. labor, religious, ecological boycotts). Earlier studies indicate that some motives are universal and some are specific for the type of boycott under consideration. For example, consumers consider the perceived efficacy and the possibility of free-riding with regard to different types of boycotts (e.g. due to animal experiments, price increases, or factory closures; Klein et al., 2004; Sen et al., 2001). It seems that these antecedents are universal, whereas other drivers are case-specific. For boycotts due to factory closure, for instance, scholars have already ascertained idiosyncratic drivers, such as the danger of a boomerang effect or the reputation of the subsidiary to be closed, which are not transferable to other types of boycott (Hoffmann and Mu¨ller, 2009; Klein et al., 2004). Presumably, participation in this type of boycott is also motivated by several additional factors neglected so far, such as solidarity with the dismissed co-workers and a negative attitude towards globalization. In contrast, participating in other types, is caused by other idiosyncratic drivers. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of boycott participation, this study highlights the importance of case-specific investigations. We show that sole reliance on boycott drivers that are derived from general boycott theories draws an incomplete picture of participation. We investigate whether idiosyncratic drivers of participation have been neglected because scholars based their investigations mainly on general theories of boycotting. We have chosen the example of boycotts due to factory relocations, because they are highly relevant from a practical point of view. In the industrialized countries the fear of becoming unemployed because jobs are exported drives many people to boycott in order to prevent or at least to protest against offshoring. After Nokia announced its planned relocation of the German subsidiary to Romania, 56 percent of German consumers intended to avoid purchasing Nokia mobile phones (Weber, 2008).

چکیده

1. مقدمه و پیشینه

4. نتیجه

5. محدودیت ها و پژوهشِ بیشتر

منابع

Abstract

1. Introduction and background

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and further research

References