دانلود رایگان مقاله تصویربرداری کاربردی از خون رسانی مغزی

چکیده

تصویربرداری کاربردی از پرفیوژن بررسی مشخصات آن مانند پاسخگویی به گازهای در حال گردش، تنظیم خودکار و کوپلینگ عصبی عضلانی را ممکن میسازد. جریان رو به پایین تنگی شریانی در این تصویربرداری میتواند ذخایر عروقی و خطر کمخونی (ایسکمی) را در جهت تطبیق استراتژی درمانی تخمین بزند. این روش اختلالات همودینامیکی را در بیماران مبتلابه بیماری آلزایمر یا ناهنجاریهای عروقی ناشی از صرع نشان میدهد. MRI کاربردی از پاسخگویی نیز به درک بهتر انجام MRI کاربردی در تحقیقات عملی و درمانی کمک میکند.

نکاتی در مورد پرفیوژن مغزی

مطالعه پرفیوژن مغزی برای درک کاربردی سیستم عصبی مرکزی و از بین بردن اختلالات عملکردی آن، که از دلایل اصلی مرگومیر در غرب است؛ اطلاعات مهمی ارائه میدهد. در مغز و اعصاب و روانپزشکی، تشخیص این اختلالات پاتوفیزیولوژیکی عروقی ممکن است اطلاعاتی ارائه دهد که به تشخیص بهتر چند بیماری و یا حتی بررسی آسیبپذیری فردی کمک میکند.

علاوه بر اینها، پرفیوژن مغزی اجازه انتقال مقدار کافی گلوکز و اکسیژن را برای نیازهای کاربردی مغز میدهد، درحالیکه گرما و برخی کاتابولیت ها مانند CO_2 را حذف مینماید [1]. پرفیوژن یک پدیده فیزیولوژی دینامیک است که به تغییرات هموستاز (هم ایستایی) در اندام عضلانی و کل بدن پاسخ میدهد. مانند هر عملکرد بیولوژیکی، عوامل کلی و محلی نهتنها وضعیت تعادلی بلکه خواص سازگاری آن را نیز تغییر میدهند. این تنظیم در اثر مشخصات مکانیکی رگهای خونی غیرفعال و با تغییر شریانی رگها فعال میشود. تغییر شریانی کالیبراسیون عروق را کنترل مینماید، همانطور که ذخیره خون را در حین تغییرات در فعالیت عصبی (کوپلینگ عصبی عضلانی)، فشار پرفیوژن مغزی (تنظیم خودکار)، مقدار کربن دیاکسید (کپنیا)، اکسیژن و PH خون (واکنشپذیری شریانی) ثابت نگه میدارد [1].

پرفیوژن مغزی بهسادگی توسط جریان خون مغزی (CFB) تشخیص داده میشود، که بهصورت حجم خون انتقالی توسط جرم بافت مغزی بر واحد زمان تعریف میشود (بهطور استاندارد برحسب ml/100g بافت مغزی/دقیقه بیان میشود). ازآنجاکه چگالی بافت مغزی نزدیک به آب است، جرم به حجم تبدیل میشود، در این صورت CFB برحسب درصد بافت خونرسانی شده بر ثانیه (s^(-1)) بیان میشود (جدول 1). اندازهگیری مستقیم این خاصیت دینامیک بسیار مشکل است. این امر موجب پیشرفت روشهای کمتر یا بیشتر تهاجمی چندگانهای شد که میتوانستند کموبیش در انسان به کار گرفته شوند. بنابراین مقیاسها و مدلهای تحلیلی متعددی با مزایا و معایبشان ارائه شدند [1,2]. روشهای اولیه مانند آنهایی که توسط کتی و اشمیت با استنشاق NO_2 توسعه یافتند [3] ، یک CFB کلی بر اساس تجزیهوتحلیل غلظت شاخص در ورودی و خروجی سیستم شریانی اندازهگیری میکردند. در تصویربرداری، CFB در مقیاسی از ناحیه مغزی (rCFB)، یا حتی پیکسلی از یک تصویر دیجیتالی و واکسل (کوچکترین جزء تصویر سهبعدی) با تکنیکهای پرتونگاری اندازهگیری شد. در دهههای اخیر، تصویربرداری به دلیل کاهش عمده در روندهای غیرتهاجمی و افزایش در بزرگنمایی زمانی و مکانی با موفقیت روبهرو بوده است، که این موجب تلفیق rCFB با CFB شده است.

جریان خون مغزی و حجم خون مغزی (CVB) دو پارامتر فیزیولوژیکی نزدیک به هم هستند، زیرا به تغییرات در مقاومت شریانی وابستگی دارند. مکانیک سیالات تغییر در حجم را با جذر تغییر در جریان مرتبط میسازد. در مغز و اعصاب، این نسبت بهصورت ([V/V_0 ]=[F/F_0 ]^α) تخمین زده میشود.

V_0و F_0 بیانگر حجم و جریان در حالت اولیه، و V و F بیانگر حجم و جریان در حالت نهایی هستند. با تلفیق تجربی پرفیوژن مغزی توسط CO_2، α تقریباً برابر با 0.4 in در حیوان تخمین زده شد[4-6]. در انسان، مقدار α بین 0.29 و 0.73 با اختلافات ناحیهای بالا گزارش شد [7,8]. این ناهمگونیها احتمالاً به اختلاف بین روشهای اندازهگیری[9]، تنوع ناحیهای در تراکم مویرگی[10,11]، مکانیزم فیزیولوژی مورداستفاده برای تلفیق پرفیوژن[7,12,13]، فاصله زمانی بین تغییرات اولیه در CFB که عمدتاً بر پایه بخشهای مویرگی و شریانی هستند و تغییرات بعدی در CVBمنعکسکننده بخش سیاهرگی، برمیگردند[6,14,15].

تغییرات فیزیولوژیکی در پرفیوژن مغزی

در حالت استراحت، پرفیوژن مغزی با سن کاهش مییابد [16] و بهطور قابلملاحظهای در زنان بیشتر است[17]. پرفیوژن مغزی بسیار مرتبط با فعالیت مغز است. آن اغلب در علم مغز و اعصاب و پزشکی اندازهگیری میشود زیرا تعامل میان رگها و اعصاب را از طریق کوپلینگ عصبی عضلانی منعکس مینماید. بهعلاوه، پرفیوژن مغزی نسبتاً ثابت است تا بهوسیله تنظیم خودکار با تغییرات فشارخون و فشار درون جمجمهای مقابله کند. پرفیوژن مغزی به تغییرات غلظت شریانی در CO_2 و O_2 با واکنشپذیری شریانی نیز حساس است (شکل 1). تمام این عملکردهای فیزیولوژیکی بر اساس تغییر شریانی هستند که از طریق انبساط و انقباض رگها جهت تنظیم جریان خون مغزی ایجاد میشوند تا فعالیت مغزی را با مقابله با محدودیتهای فیزیولوژیکی محلی و کلی تضمین نمایند [18].

فلشهای کامل رابطه مثبت و فلشهای نقطهچین رابطه منفی را نشان میدهند. کالیبراسیون شریانی توسط کوپلینگ عصبی عضلانی ناشی از فعالیت عصبی، واکنشپذیری شریانی به O_2 و CO_2، تنظیم خودکار فشار پرفیوژن (که برابر با اختلاف فشار میان میانگین فشار شریانی و فشار درون جمجمهای است) تنظیم میشود. افزایش جریان خون مغزی (CBF)، به بالاتر از نیاز سلول، کسر استخراج اکسیژن (OEF) را کاهش و حجم خون مغزی (CBV) را افزایش میدهد، درحالیکه مقدار هموگلوبینهای بدون اکسیژن (deoxyHb) را در واکسل کاهش میدهد. به دلیل اینکه deoxyHb پارامغناطیس است، T2 کاهش مییابد. این کاهش، حساسیت سیگنال را به اثر BOLD در تصویربرداری افزایش میدهد.

تحریک عصبی در تشکیل عروق خونی عصبی

تحریک عصبی بیرونی

تحریک عصبی شریانی بیرونی عروق خونی از سیستم عصبی محیطی با غدد عصبی گردنی، اسپنئوپالاتین، سهقلو و بصری حاصل میشود که اطلاعات را از فشارگیر محیطی (انتهای عصب که نسبت به فشارخون واکنش نشان میدهد و میزان گشادی عروق را تنظیم میکند) میگیرند. تحریک عصبی بیرونی عمدتاً سکته مغزی (نورآدرنالین، سروتونین، نوروپپتید Y) و گشادی رگ پراهمسوهشی (پاراسمپاتیک، وابسته به دستگاه عصبی نباتی) (اکتیل کولین، نیتریک اکسید، VIP) است. شریانها بهطور تدریجی به سرخرگهایی تقسیم میشوند که به بافت اصلی مغز وارد میشوند. آنها شامل یک لایه درونی از سلولهای آندوتلیال (درونپوش)، سلولهای عضلانی صاف و یک لایه بیرونی از سلولهای لپتومنینگیل (پوشش بیرونی مغز) هستند که پوشش خارجی را تشکیل میدهد. سرخرگ بهوسیله فضای Virchow-Robin از بافت اصلی جدا میشود که این فضا مایع مغزی نخاعی را دربرمی گیرد و با آستروسیت ها (سلول گلیال ستارهای سیستم عصبی مرکزی) روی سطح خارجی پراکندهشده است. ازآنجاکه سرخرگها وارد بافت اصلی میشوند، فضای مایع ناپدید میشود و سرخرگها و سپس مویرگها در تماس مستقیم با پایه آستروسیت هایی هستند که به گلیا (بافت پشتیبان سیستم عصبی) محدود میشوند [19-21].

Abstract

The functional imaging of perfusion enables the study of its properties such as the vasoreactivity to circulating gases, the autoregulation and the neurovascular coupling. Downstream from arterial stenosis, this imaging can estimate the vascular reserve and the risk of ischemia in order to adapt the therapeutic strategy. This method reveals the hemodynamic disorders in patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease or with arteriovenous malformations revealed by epilepsy. Functional MRI of the vasoreactivity also helps to better interpret the functional MRI activation in practice and in clinical research.

Reminders about cerebral perfusion

The study of cerebral perfusion provides critical information to understand the functioning of the central nervous system and apprehend its dysfunction, among the main causes of morbidity and mortality in the West. In neurology and psychiatry, the identification of these microvascular pathophysiological disorders may provide information that may help to better characterize a several diseases, or even assess individual vulnerability.

Above all, cerebral perfusion allows for the transfer of appropriate quantities of glucose and oxygen for the functional needs of the brain, while eliminating heat and some catabolites such as CO2 [1]. Perfusion is a dynamic physiological phenomenon able to respond to changes in the homoeostasis of the vascularized organ and the entire body. Like any biological function, general and local factors are likely to not only modify its state of equilibrium but also its adaptive properties. This adjustment is both passive, due to the mechanical characteristics of blood vessels, and active by the arteriolar vasomotricity. The vasomotricity controls the caliber of the arterioles, so as to maintain the blood supply during variations in neuronal activity (neurovascular coupling), cerebral perfusion pressure (autoregulation), capnia, oxygenation and pH (vasoreactivity) [1].

Cerebral perfusion may simply be characterized by the cerebral blood flow (CBF), defined by the volume of blood transiting by the mass of the cerebral parenchyma per unit of time (classically expressed in ml/100 g of cerebral parenchyma/min). Since the density of brain tissue is close to that of water, the mass is often converted into volume, allowing the CBF to be expressed as a percentage of the parenchyma perfused per second (s−1) (Table 1). The direct measurement of this dynamic property is especially difficult. This has given rise to the development of multiple, more or less invasive, methods that can, more or less, be considered in man. Numerous indicators and analytic models, with their advantages and disadvantages, have thereby been proposed [1,2]. The initial methods, such as those developed by Kety and Schmidt with the inhalation of NO2 [3], measured a global CBF based on the analysis of the concentration of the marker at the entry and exit from the vascular system. In imaging, the CBF is measured on the scale of a cerebral region (rCBF), or even the pixel of a digital image and the voxel with tomography techniques. The success, over the last decades, of the imaging that has been established due to a major reduction in the invasiveness of the procedures and an increase in the temporal and spatial resolutions, has led to assimilate the rCBF with the CBF.

The cerebral blood flow and the cerebral blood volume (CBV) are two physiologically, closely related parameters, since they depend on the variations in arteriolar resistance. The mechanics of the fluids proportionally links variations in the volume with the square root of variations in flow. In the neurosciences, this ratio is estimated by: ([V/Vo] = [F/Fo])

Vo and Fo representing the volume and flow at the initial state, and V and F the volume and flow at the final state. With an experimental modulation of the cerebral perfusion by CO2, was estimated as being close to 0.40 in the animal [4—6]. In man, values of between 0.29 and 0.73 have been reported with high regional disparities [7,8]. These heterogeneities are likely to reflect differences between the methods of measurement [9], the regional variability of the capillary density [10,11], the physiological mechanism used to modulate the perfusion [7,12,13], the time interval between the early variations in the CBF that are mainly based on the arteriolar and capillary sectors, and later variations in the CBV that better reflect the venous sector [6,14,15].

Physiological variations in cerebral perfusion

At rest, the cerebral perfusion decreases with age [16] and is significantly higher in women [17]. The cerebral perfusion is closely related to the activity of the brain. It is often measured in the neurosciences and in medicine since it reflects the interaction between the vessels and the neurons through neurovascular coupling. Moreover, the cerebral perfusion is maintained roughly constant in order to deal with variations in the blood pressure and intracranial pressure by autoregulation.

The cerebral perfusion is also sensitive to variations in the arterial concentration in CO2 and O2 by the vasoreactivity (Fig. 1). All of these physiological functions are based on the vasomotricity that enables, through the dilation and contraction of the vessels, to adjust the cerebral blood flow in order to guarantee the cerebral activity by dealing with the general and local physiological constraints [18].

Innervation of cerebral vascularization

Extrinsic

innervation The extrinsic vascular innervation of the pial arteries arrives from the peripheral nervous system by the upper cervical, sphenopalatine, trigeminal and optical ganglions that relay the information from peripheral baroreceptors. The extrinsic innervation is mainly sympathetic vasoconstrictor (noradrenalin, serotonin, neuropeptide Y) and parasympathetic vasodilator (acetylcholine, nitric oxide, VIP). The arteries progressively divide into arterioles that enter the cerebral parenchyma. They consist of an internal layer of endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and an outer layer of leptomeningeal cells that form the external tunic. The arteriole is separated from the parenchyma by the VirchowRobin space that contains the cerebrospinal fluid and is bordered by astrocytes on the outside. As the arterioles enter the parenchyma, the fluid space disappears and the arterioles and then the capillaries are in direct contact with the feet of the astrocytes that form the glia limitans [19—21].

چکیده

نکاتی در مورد پرفیوژن مغزی

تغییرات فیزیولوژیکی در پرفیوژن مغزی

تحریک عصبی در تشکیل عروق خونی عصبی

تحریک عصبی بیرونی

تحریک عصبی درونی و واحد عصبی عضلانی

کوپلینگ عصبی عضلانی

تنظیم خودکار فشار مغزی

واکنشپذیری شریانی به گازهای در حال گردش

واکنشپذیری شریانی به CO_2

واکنشپذیری شریانی O_2

تصویربرداری عملکردی از پرفیوژن مغزی

تأثیر شرایط اولیه

تصویربرداری از کوپلینگ عصبی عضلانی

تصویربرداری از تنظیم خودکار

تصویربرداری از واکنشپذیری شریانی

اندازهگیری مقدار واکنشپذیری شریانی مغز

مقدار کوپلینگ عصبی عضلانی در تصویربرداری عملکردی

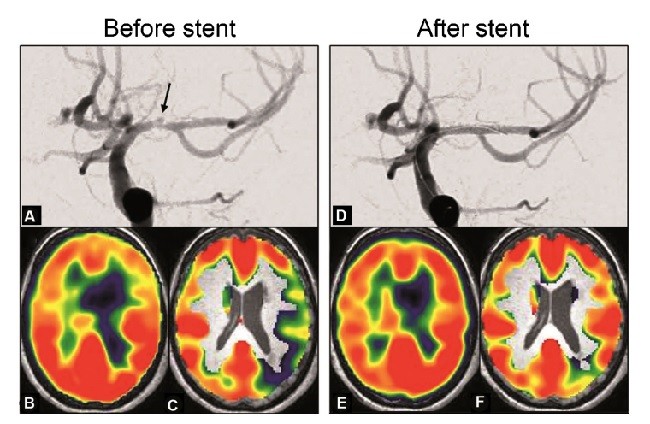

ارزش پیشبینی در بیماری انسداد رگ

تصویربرداری بعدی از واکنشپذیری شریانی برای اهداف تشخیصی

روشهای اندازهگیری واکنشپذیری شریانی مغز

انتخاب روش تصویربرداری

انتخاب تحریک محرک شریانی

نتیجهگیری

پیامهای دریافتی

Abstract

Reminders about cerebral perfusion

Physiological variations in cerebral perfusion

Innervation of cerebral vascularization

Extrinsic innervation

Intrinsic innervation and the neurovascular unit

Neurovascular coupling

Autoregulation of cerebral pressure

Vasoreactivity to circulating gases

Vasoreactivity to CO2

O2 vasoreactivity

Functional imaging of cerebral perfusion

Influence of the initial conditions

Imaging of the neurovascular coupling

Imaging of autoregulation

Imaging of vasoreactivity

Value of the measurement of the cerebral vasoreactivity

Value of neurovascular coupling for functional imaging

Prognostic value in steno-occlusive disease

Towards imaging of the vasoreactivity for diagnostic purposes

Techniques to measure cerebral vasoreactivity

Choice of imaging method

Choice of vasomotor stimulus

Conclusion

Disclosure of interest

Acknowledgements

References